Authors

José Manuel Campa and Mario Quagliariello[1]European Banking Authority (EBA). This article is based and elaborates on José Manuel Campa’s speech “The regulatory response to the Covid-19 crisis: a test for post GFC reforms” at the … Continue reading

1. Introduction

Since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), the European banking sector has made significant progress in restoring resilience and market confidence. At the beginning of 2020, while there were still significant challenges ahead – not least the structurally low profitability and pockets of idiosyncratic vulnerabilities particularly in mid-sized banks – the positive trend was robust and consolidated. Banks and supervisors were actively addressing remaining weaknesses, and market participants were expecting decisive steps towards the completion of the balance sheet repair.

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic was an unprecedented test for the economy and made any forecasts outdated and obsolete. Organisations, professionals and individuals have gradually adapted to the new conditions and learnt how to mitigate the operational difficulties and emerging risks of a worldwide pandemic. Yet, with the vaccination campaigns progressing at uneven pace in different jurisdictions and widespread uncertainty on the start and speed of economic recovery, many challenges lie ahead. This is true for the health systems, the economies as well as the banking sector.

The exceptional measures adopted globally in response to the first wave of the epidemic have brought the global economic activity to a sudden freeze. Because of the various forms of population confinement – such as lockdowns and social distancing – the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has markedly declined in the EU and at the global level and the path to recovery remains uncertain.

The impact of Covid-19 largely depends on how successful governments are going to be in their vaccination campaigns, limiting the spread of new variants and preventing further waves. The effectiveness of the actions taken to support the economy will also determine the pace of economic recovery.

Banks were not the source of this crisis, nor have they been the most affected sector. Thanks to strong starting positions and unprecedented public measures to support the economy, the banking sector proved able to absorb the initial shock, remain resilient, and provide liquidity to struggling households and firms.

The combination of inner strength and prompt supervisory responses allowed banks to play an important role in supporting the economy during the heights of the crisis also thanks to the exceptional monetary and fiscal policies. EU supervisory authorities demonstrated the capacity to act quickly, resolutely, and effectively to mitigate the impact of the crisis on the financial sector. The European Banking Authority (EBA) took a number of steps, first, to facilitate banks to continue providing financing to households and corporates at a very difficult juncture and, second, to monitor the evolution of the crisis in order to adjust its measures as deemed necessary.

However, as the pandemic continues to affect the economy, a legitimate question arises of whether banks will be able to absorb the full impact of the crisis as they continue providing adequate lending to the economy. Unquestionably, the crisis will also have longer-term implications on the future shape of the banking sector. There are some additional questions on whether the regulatory framework is fit for purpose to allow banks to pursue these goals.

In this article, we try to address these questions with a focus on the European Union. We describe how banks entered the crisis, explain the rationale for the actions taken as the immediate response, provide some initial thoughts on the lessons learnt and try to look forward and sketch some possible implications for future policy-making.

2. Banks at the start of the crisis

European banks entered the Covid-19 epidemic with relatively high capital levels and abundant liquidity buffers, particularly when compared to the recent past. The solvency level of EU banks had improved significantly since the GFC (chart 1) and, more importantly, the cross-sectional dispersion reduced materially, with banks in the lower quartile catching up steadily. In December 2019, EU banks’ Common Equity Tier 1 ratio (CET1) was 15.1% on average and banks were comfortably above regulatory minima. The management buffer – which is the additional capital banks hold in excess of capital requirements, buffers and supervisory expectations – was 300bps. This trend of higher capital ratios – which is also visible when looking at the evolution of non-risk-weighted metrics such as the leverage ratio – has been driven by both deleveraging and the increase in own funds, also in connection with the gradual adjustment to the Basel 3 standards.

Chart 1 – EU Banks: Common equity tier 1 (CET1) ratio

Similarly, liquidity buffers were ample, with the Leverage Coverage Ratio (LCR) close to 150% (chart 2). Also in this case, the contraction of the interquartile range and the overall move upwards of the distributions are impressive and confirm that the progress was widespread. Banks’ funding mix was also more balanced and stable, with a steady increase of the share of household and non-financial corporation deposits since the GFC. In contrast to previous recent crises, available liquidity buffers increased even further in 2020, in connection with massive central banks interventions providing cheap funding to the banking sector. Banks also benefited from favourable conditions in wholesale funding markets in the quarters before the outbreak of COVID-19.

Chart 2 – EU Banks: Liquidity coverage ratio (LCR)

Banks had also significantly reduced non-performing loans (NPLs) and improved asset quality, with an acceleration after the approval of the Council’s NPL action plan in 2017. With the introduction of a common definition of NPLs, the EBA provided the regulatory framework and monitoring mechanism that allowed supervisors to push banks strategies.

Since 2014, NPL volumes have more than halved (chart 3) and the progress, while generalised, was more pronounced for countries with higher starting NPL ratios. The positive downward trend affected all sectors and asset classes and was achieved through both internal organic workout and disposals in secondary markets, either portfolio sales or securitisations. However, the pace of the adjustment in the sector could have been faster. The NPL ratio in 2019 stood at 3.1% on average, higher than in other advanced economies, with many countries still showing levels well above those recorded before the GFC.

Chart 3 – EU Banks: Non-performing loan (NPL) ratio

Despite the efforts put by banks in repairing their balance sheets and improving asset quality, a number of challenges remained in the industry. Banks’ profitability had not recovered since the GFC, with returns remaining subdued amidst low interest rates and banks’ difficulties in reducing operating expenses (chart 4). For many banks, the return on equity has not covered the cost of equity for many years, as also reflected in their market valuations.

Chart 4 – EU Banks: Return on Equity (RoE)

Persistent low profitability, and remaining pockets of poor asset quality, along with competitive pressures coming from new digital players, are likely to be exacerbated by the current crisis. Supervisory measures adopted in 2020 provided an immediate response to short-term tensions and the sudden halt of economic activities. However, banks still need also to address long-term outstanding problems, which require structural reforms.

3. A review of the regulatory response

The immediate reaction of the supervisory community to Covid-19 and the gradual deployment of containment measures by governments aimed at ensuring business continuity in such difficult circumstances. It was important that banks were able to serve the economy and their customers, avoiding the collapse of credit to the real economy at the very moment when it was required to transmit fiscal stimulus to corporates and households.

The rationale of the measures adopted by the supervisory community was clear. The target was to safeguard business continuity in the sector, allow banks to use the capital and liquidity buffers accumulated over time, and remove any unintended obstacles to the widespread use of public support measures.

Regulators provided operational relief to banks, allowing them to shift resources where mostly needed. This decision was not made lightly. Postponing the ongoing 2020 EBA EU-wide stress test exercise by one year, delaying remittance dates for supervisory reporting, and putting on hold consultation processes determined a loss of valuable information, in particular on banks’ latest conditions, at the very moment authorities actually needed it the most. Nevertheless, this was the right thing to do in exceptional circumstances, with banks in great need to focus on critical functions and operational resilience.

The EBA recognised the need for a pragmatic approach in the 2020 Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) as well as for recovery planning, and recommended that supervisory authorities focus their efforts on the most material risks and vulnerabilities driven by the crisis.

At the global level, the implementation of the Basel 3 standards finalised in December 2017 was deferred by one year to January 2023. In Europe, the EBA reminded that capital – and liquidity – buffers accumulated by banks over time were a reserve to absorb losses but also to ensure continued lending to the economy. In the same spirit, several macroprudential authorities released the countercyclical buffers and supervisors allowed banks to operate below their Pillar 2 Guidance (P2G). It was also clarified that part of the Pillar 2 requirements could be covered with instruments other than CET1.

With the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) ‘quick fix’, which was approved by the European Parliament in June 2020, the transitional arrangements for smoothing the impact on capital of the introduction of International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 9 on own funds were extended by 2 years. Other measures already in the pipeline – for instance a revised and more generous supporting factor for lending to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) – were introduced ahead of schedule. The EBA also frontloaded the rules on the prudential treatment of software investments introducing their partial deduction from capital.

The corollary of capital relief measures was the recommendation to banks to follow prudent dividend distribution policies. Dividend restrictions and bans forced banks to preserve capital with an overall impact of about 40 billion Euros. This was a controversial measure, with a few stakeholders arguing that a case-by-case approach would have been better than a generalised restriction. However, a system-wide approach was proportionate to the severity of the crisis and the uncertainty on its effects. A case-by-case approach would have not achieved the same objective and the stigma effect on some banks could have adversely affected those intermediaries in more urgent need of support.

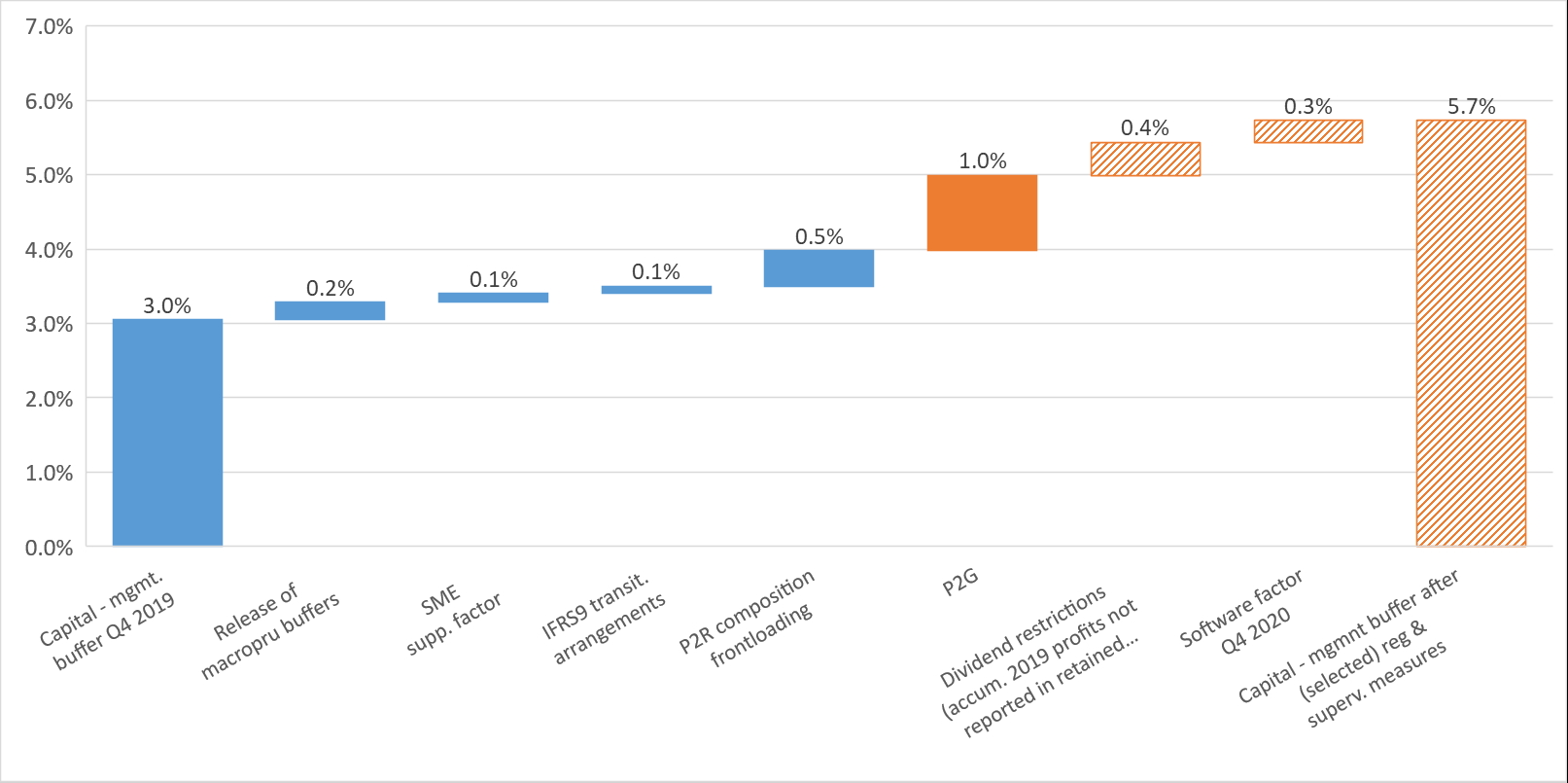

We have mentioned already that banks entered the crisis with good solvency positions and a management buffer of about 300bps of RWAs in December 2019 (chart 5).

Chart 5 – Evolution of management buffers in 2020

Capital related measures had the objective of further enhancing banks’ ability to finance the economy, thus creating additional headroom for lending. Taken together, these measures contributed to free up capital, with the management buffer increasing to 570 bps assuming the full use of P2G. However, the availability of buffers was uneven across the EU due to the different starting position of banks and to the diverse implementation of macroprudential measures across Europe.

The EBA also intervened to avoid any unintended reclassification in default status for debtors in temporary liquidity difficulties. In particular, there was a pressing need to address the prudential treatment of legislative and non-legislative payment moratoria, which were introduced by several countries as a support measure to provide payment breaks to borrowers. The EBA published guidelines[2]EBA (2020), Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the

light of the COVID-19 crisis. to clarify that the payment moratoria do not automatically trigger forbearance classification and the assessment of distressed restructuring if they are based on the applicable national law or on an industry-wide initiative agreed and applied broadly by relevant credit institutions.

These guidelines were necessary for avoiding the automatic reclassification in forborne or defaulted status of loans under moratoria, but they also confirmed the necessity of a timely and accurate measurement of credit risk. They safeguarded borrowers with temporary liquidity problems, but did require the assessment of the long-term unlikeliness to pay.

The emergency determined by Covid-19 called for emergency measures. However, it was – and it is – important to preserve the correct measurement of risks and the reliability and timeliness of risk metrics. Therefore, the EBA also put in place adequate tools in order to enable supervisors and stakeholders to monitor these exposures and adequately assess the evolving situation in the banking sector. The EBA introduced ad-hoc reporting and disclosure requirements for the exposures benefitting from moratoria and public guarantees. This allows supervisors to understand the materiality of the exposures as well as their classification for prudential and accounting purposes.

4. Is this time different?

Capital ratios have improved further since March 2020, NPLs have not increased and liquidity has remained ample. Compared with the previous crises, bank lending to the real economy has increased, particularly in the first half of 2020. In the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, non-financial corporations (NFCs), especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), made use of available loan commitments to secure liquidity and operational continuity. Later on, credit demand was mostly driven by government guaranteed loans.

The increase in lending, along with the surge in cash balances that followed central bank extraordinary liquidity allotments, has resulted in a 9% increase in total assets in the first three quarters of 2020. This figure could slightly underestimate the size of asset growth since, in some jurisdictions, fully guaranteed loans can be derecognised by banks and, thus, are not visible in their balance sheets.

In this section, we explore further the data available at the EBA, with a focus on banks’ use of moratoria and deposit guarantees and forward-looking indicators of asset quality[3] EBA (2020), First evidence on the use of the moratoria and public guarantees in the EU banking sector.. This should provide a more accurate picture of the future evolution of credit risk, beyond headline figures.

In September 2020, EU banks reported EUR 587 billion of loans under moratoria compliant with the EBA guidelines, which represents around 5% of the total outstanding loans to households and NFCs. Banks also reported that moratoria had expired for about EUR 350bn of loans. The use of moratoria was heterogeneous across countries, reflecting the different timing and impact of the epidemics as well as the variety of national support measures deployed by governments.

Loans under moratoria were around 6% for NFC, whereas 4% of household loans had been granted some form of payment holidays in September 2020, which is about half the amount recorded in June. Moratoria were more widely used by small and medium enterprises, which typically rely more on bank credit for financing their funding needs. About 55% of the moratoria had a maturity of less than 3 months, and around 85% of them were to mature before March 2020.

The EBA guidelines require banks to perform the usual due diligence on asset quality evolution and, in particular, on debtors’ likeliness to pay. Therefore, the evolution of credit risk for loans under moratoria provides valuable information on the quality of these loans as well as on banks’ risk management approach during the pandemic. In September 2020, about 20% of loans under moratoria were classified as stage 2, which is more than double the share for total loans. The NPL ratio for loans subject to moratoria was 3%, which is slightly higher than the EU average (2.8%). This is, however, not surprising considering that some national schemes included only performing loans as eligible for payment moratoria. In our view, this suggests that banks, to some extent, have been proactive in assessing the unlikeliness to pay – in the absence of past-due criterion for the loans under moratoria – as well as any material increase in credit risk triggering the migration of loans from Stage 1 to Stage 2. On the other hand, this is also in line with the evidence that moratoria reached the intended recipients – i.e., the economic sectors most affected by the crisis – which tend also to be riskier.

The use of public guarantees (PGS) was also widespread. In September 2020, newly originated loans subject to PGS amounted to around EUR 289 billion. This volume represents a relatively small share of the stock of total loans on average (about 1.6%) but is material for some banks and jurisdictions. Public guarantees were granted predominantly for loans to NFCs, which represented almost 94% of all new loans benefitting from PGS. PGS impact on banks’ lending was rather significant in the countries more affected by the first wave of Covid-19 contagion.

Public guarantees have the potential to reduce significantly banks’ RWAs. In September 2020, banks reported RWAs of EUR 45 billion for exposures subject to PGS of EUR 289 billion. This implies an average risk weight of around 16%, which can be compared with an average risk weight for banks’ NFC exposures of 54%[4]EBA (2020), Risk Assessment of the European Banking System. According to estimates, this corresponds to a benefit in terms of CET1 ratio ranging between 10 and 20 basis points.

Overall, public support measures – both on the fiscal and prudential side – along with very low interest rates did shield the banks from the first round effects of the crisis. NPL ratios and volumes remained low and the declining trend was confirmed, even though at slower pace than pre-Covid-19.

However, there are also early signals of asset quality deterioration, particularly looking at more forward-looking indicators. The volume of loans classified under IFRS 9 stage 2 – those that are still performing but for which there was a significant increase in credit risk – increased by 24% to EUR 1.2bn in 2020, bringing their share to 8% of total loans. A similar trend was observed for forborne loans, which can at some point turn into non-performing status if the conditions of the restructured debtors worsen further.

This dynamic was also reflected in profit and loss accounts. Banks have booked substantial provisions on performing loans that resulted in a material increase in the cost of risk, albeit with significant dispersion. As a result, the cost of risk – the ratio between the flow of impairments and total loans – was significantly higher than in 2019 (0.74% in Q3 2020 vs 0.46% in Q3 2019). Profitability deteriorated quickly due to increased provisions and plummeted to zero in Q1 2020, with a moderate recovery in the following quarters. Pressure on interest margins will not decrease anytime soon, as the low or negative interest rate environment is expected to persist for even longer.

While it is difficult to make accurate forecasts on the timing and materiality of asset quality deterioration, all these elements point to a new wave of NPLs in the coming quarters. According to a sensitivity analysis carried out by the EBA for assessing the impact of COVID-19 on EU banks, stage 3 assets could increase to levels comparable to 2014 and credit risk losses could determine a decline of CET1 ratios between -230bps to -380bps, without taking into account the mitigating impact on impairments of PGS[5]EBA (2020), The EU Banking Sector: First insights into the COVID-19 impacts.. EU banks would have, on average, enough capital buffers for absorbing these losses, but there could be cases requiring corrective measures. While we are cautious in interpreting these results given the uncertainty on future economic conditions and the mitigating impact of the government support measures, this is an area that requires close monitoring, proactive actions and enhanced policy toolkit. Currently, the EBA is performing its biennial stress test exercise of European banks, which will provide a more detailed account on the status of the banking sector and its ability to weather a severe downward macroeconomic scenario.

There are ways to mitigate the impact of the expected increase of credit risk on financial stability. First, it is for banks to proceed with the early and transparent recognition of any deterioration of asset quality. It is imperative that investors do not lose their trust in the EU banking sector as in the aftermath of the GFC, when banks – notwithstanding the strengthening of capital positions – were perceived to be hiding losses in their balance sheets. Banks need to have enough provisions. This crisis may be less harmful than we expect or the recovery faster but, at this stage, it is safer to err on the conservative side and reverse provisions later.

Low for long interest rates can have a positive mitigating impact on credit risk, but it should not lead to unjustifiable delays of non-viable firms, nor to the delay in recognition of potential non-performing exposures. The same principle should apply to the banking sector itself. The low interest rate environment should also not delay a long-due restructuring of the sector and the orderly exit of weaker banks. In addition, low for longer interest rates will make it harder to regain profitability through credit intermediation. Banks need to redefine their business models, find other income sources, partly embracing innovation but also leveraging on their traditional competitive advantage in serving their customers, offering advice and higher value added services, and supporting their migration towards a greener economy.

5. Lessons for regulation

All crises are different but they also share similar patterns. In the midst of the turmoil, economic agents tend to react looking primarily within their private interests and cooperation and coordination suffer. At the national level, this results in actions being taken pursuing national objectives and, at times, with insufficient coordination. This is understandable when there is an urgency to act under time pressure and uncertainty, but it is far from optimal and can jeopardise the overall economic recovery and the level playing field.

The reaction to this crisis shows a mix of national bias and a strong, genuine effort to provide a common EU response with stronger coordination. On the one hand, the actions at the European level have been unprecedented, particularly when compared with previous crises. The monetary policy, macroprudential and supervisory responses were quick and well-coordinated. More importantly, the EU agreed on a long-term budget that, coupled with NextGenerationEU, represents a strong commitment to deliver an EU-wide post-crisis stimulus package financed through the EU money.

On the other hand, the immediate public support provided to the economy was diverse across countries and commensurate to the fiscal capacity of the single Member States. Payment moratoria and public guarantee schemes affecting the banking sector were launched from national initiatives with little or no supranational coordination, different deadlines, coverage and conditionality. The EBA tried to provide with its guidelines on moratoria a harmonised framework for the prudential treatment of such measures. However, the policies implemented remain different in many aspects.

Going forward, it is important that the interaction of these policies with the need for orderly restructuring of the corporate sector as a result of the crisis does not result in a fragmentation of the single market and an uneven playing field within the EU banking sector.

The crisis has also proven that the regulatory reforms agreed at the global level in the aftermath of the GFC have been successful in strengthening banks’ resilience. While the long-term impact of Covid-19 is still to be determined, high capital, ample liquidity, improved asset quality, enhanced digital capacity, stronger risk management helped banks to respond to the emergency. This confirms the importance of a sound regulatory framework and its effective implementation. Globally agreed standards have helped us manage this crisis and have confirmed their overall usefulness. This is a lesson for the future.

Regulatory authorities have proved to be up to the challenge and willing to make full use of the flexibility permitted in the prudential and – to the extent possible in their remit – the accounting frameworks. Flexibility was increased by the legislator where it was deemed necessary. Some rules, particularly on the treatment of non-performing assets, required some fine-tuning, but, overall, we did not change their philosophy confirming the need to timely recognise and measure risks, while avoiding automatisms that can determine unintended consequences in case of systemic crisis and system-wide support measures.

Authorities allowed banks to support the economy, while demanding the preservation of reliable risk metrics. The distinction between short-term liquidity difficulties and insolvency – or unlikeliness to pay – was crucial in squaring this circle and proved fit for purpose. The evidence on the classification of loans under moratoria provides some initial reassurance that banks have implemented supervisory guidance as required. However, it is important that credit risk is monitored carefully so to ensure that banks identify any early signal of borrowers’ distress and provision against potential losses accordingly.

Authorities have been also proactive in triggering the countercyclical features embedded in the Basel 3 framework. Since the onset of the crisis, micro- and macroprudential, European and national authorities provided the unequivocal message that capital is there to be used. Relaxing capital requirements and encouraging banks to make use of their liquidity buffers in a crisis do not come natural to supervisors, but they are key to allow the banking sector to act as a stabiliser rather than an amplifier of the shocks. This was the very purpose of including a macroprudential perspective in the prudential standards.

Banks have, so far, made limited use of this flexibility. Until the third quarter of 2020, there is no sign of a decline in the CET1 ratio, at least on average at the EU level, and banks – with a few exceptions – are still able to meet their overall capital requirements. A first observation is that there is some confusion on the concept of buffer “usability”. Banks can use buffers to absorb losses and still be able to meet minimum requirements. This implies that buffers are used when losses are recognised. Banks can also use buffers to absorb the increase of risk-weighted assets in a crisis without reducing lending. If credit is flowing fine to the economy and the supply matches customers’ demand, then there is no need to use the buffers.

At this stage, it is too early to say whether the issue of buffer usability is material. We documented that credit did increase in the aftermath of the crisis. Banks also increased provisions, but below some analysts’ expectations.

Still, this is an important discussion looking forward. There is a view that banks are reluctant to use the buffers for reasons beyond supervisory expectations. If this is true, it is important to understand those specific concerns, their relevance, and consider whether adjustments to the framework are needed.

On the one hand, there could be a general apprehension related to the market stigma associated with the use of buffers or even with the simple decline of capital ratios. This would indicate the reluctance of market participants to accept fluctuations of capital ratios in banks as a normal – cyclical – event.

On the other hand, the scarce usability of the different buffers can be linked to the function they are expected to perform. In the prudential framework, some buffers – e.g., the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) – are inherently countercyclical since authorities can activate and deactivate the requirement depending on the evolution of economic conditions. Countercyclical, releasable buffers are designed to be used for macroeconomic adjustments.

Other buffers – e.g., the capital conservation buffer – are instead structural and work as automatic stabilisers since banks failing to meet the requirement are automatically subject to capital conservation measures. Banks can be hesitant to use the structural buffer since this may undermine their ability to payout dividends and coupons if they are at risk of breaching the overall capital requirements and, thus, triggering maximum distributable amount rules.

The relative size of the buffers determine their usability for the different economic policy objectives. This can also call for a recalibration of the buffer structure, with a greater role for buffers that can be switched off by the authorities. However, since countercyclical buffers have been built up only in a limited number of jurisdictions and to relatively limited levels, the question is whether we should also harmonise the way these buffers are deployed, pushing for a faster and larger accumulation in good times. While buffers should continue to reflect national financial conditions, some centralisation of their use at the EU level would be warranted, particularly in crisis times.

The toolkit of macroprudential authorities is also relatively weak when it comes to preserving capital in the system. While microprudential supervisors can prevent institutions for distributing dividends on a case-by-case basis, no binding instrument is available for imposing system-wide payout restrictions.

Finally, the crisis has also confirmed the urgency to complete the Banking Union and remove any obstacles to the free flow of capital and liquidity in the Single Market. National policies to address national stability concerns can often impede the free flow of funding across the union. Ring-fencing generates inefficiencies and eventually results in the inefficient allocation of resources, poor incentives to cross-border consolidation, and higher costs for customers.

6. Conclusions

The EU banking sector has been resilient so far but there are challenges ahead. The strong capitalisation and liquidity profile, coupled with the decisive response of the regulators and supervisors, have enabled the European banks to cope with the immediate impact of the crisis, while supporting their customers and governments’ efforts to push liquidity in the system. Looking forward, the key question is whether banks will be able to withstand the likely increase of credit risk losses and maintain adequate lending volumes, particularly when moratoria, public guarantee schemes and other support measures expire.

With the legacy and the experience from the GFC, it is important to be ready with credible, long-term tools to deal with the deterioration of asset quality. The 2021 EU-wide stress test will allow authorities to better assess the consequences of the crisis on banks, start discussing the appropriate way forward, and set supervisory expectations on capital planning.

Banks should do their part assuring the accurate and transparent assessment of credit risk. Capital buffers provide headroom for prudent provisioning and there is no reason for delaying risk recognition.

The Commission’s NPL action plan shows that this time is different and authorities want to be proactive rather than reactive. Asset management companies can be part of a broader toolkit within well-functioning efficient NPL secondary markets to transfer non-performing assets out of the banking sector and, while they are often associated to state-aid and resolution rules, they have a broader role to play particularly in case of widespread deterioration of credit quality. Early and proactive engagement with borrowers must be undertaken in a way that is customer centric if we are to retain public trust in financial services.

The Covid-19 crisis has also made some weaknesses in the EU banking sector more visible and accelerated some trends affecting the industry. In this sense, the crisis can represent a catalyst to restructure and make EU banks more resilient and efficient. Some issues are generalised across the sector, while others may be more idiosyncratic. The EBA analyses show that the sector is overall resilient, but banks that entered the crisis with lower capital levels, poor business models and riskier exposures may face greater challenges. In addition, further waves of contagion and a delayed economic recovery could further weaken the banking sector. Deteriorating asset quality and the ‘lower for longer’ interest rate environment are expected to weigh on an already subdued profitability.

The need to address overcapacity and advance with banking sector consolidation will become ever more important and supervisors are supporting measures to facilitate such process. A coherent and consistent application of the European resolution framework is a precondition of an orderly exit for those banks that become non-viable in the crisis. Although the challenges ahead are huge, the crisis can be the catalyst to address pre-existing vulnerabilities.

Finally, digitalisation and the use of ICT was able to progress rapidly in the crisis thanks to the work of regulators and a further acceleration could be a game-changer for banks. It could bring costs down and allow them to move towards more sustainable business models, but this should go together with careful management of ICT risks and careful consideration of the environmental and social implications of enhanced use of digital channels and machine led offerings.

The crisis triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic put the post GFC reforms in the banking industry to test, a real-life stress test of the system. We believe that the experience so far has vindicated the reforms. The philosophy behind the post-GFC regulation – more demanding requirements in normal times that can be relaxed in bad times – has been successful. This does not mean that there are not some aspects of the existing framework that may require a critical review. Changes may be necessary, but we see this as a fine-tuning and calibration of the framework rather than a fundamental rethinking of it.

We would also advocate taking enough time to reflect, discuss and make decisions. Changing the rules while the crisis is ongoing would be premature, imprudent and could be interpreted as a signal of weakness of the banking sector, at a time when markets are volatile and investors nervous. Once the health crisis is – hopefully – under control and the emergency over, it will be natural to make a stock-take of the elements that have worked well and those deserving some adjustments.

We also learnt that some flexibility in regulation may be necessary, but we should avoid reinstating national discretions. We believe it would be also advisable to go back to the roots of the Lamfalussy’s reform, with primary legislation setting only the overarching principles and leaving the technical details – which may need quick fixes – to level 3 regulation. Supervisory judgment is also important, but only if exercised under a consistent EU umbrella.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | European Banking Authority (EBA). This article is based and elaborates on José Manuel Campa’s speech “The regulatory response to the Covid-19 crisis: a test for post GFC reforms” at the Italian Banking Association, Rome, September 21, 2020. We are grateful to Valerie de Bruyckere, Valentina Drigani, and Achilleas Nicolaou for useful discussions and support. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not involve either the EBA or its Board of Supervisors. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | EBA (2020), Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis. |

| ↑3 | EBA (2020), First evidence on the use of the moratoria and public guarantees in the EU banking sector. |

| ↑4 | EBA (2020), Risk Assessment of the European Banking System |

| ↑5 | EBA (2020), The EU Banking Sector: First insights into the COVID-19 impacts. |