Authors

Ignazio Angeloni

One year has passed since the Covid-19 pandemic was discovered and recognized as such. The world economy plunged into a major recession; some areas have recovered, some are in the process of doing so while others are still deep into it. Policymakers have responded promptly with measures to protect the economy; in particular, massive support has been provided to the banking sector in the form of credit moratoria and guarantees. These measures have helped spared people, firms and banks the brunt of the crisis but have also suspended the normal functioning of the market mechanisms. As a result, the full consequences of the crisis are not visible yet. As one ECB supervisor put it to me recently, referring to eurozone banks: “we stopped the car; when we will have to start it again, we don’t k now what we will find under the hood”.

Virus and lockdowns impact the banks through multiple channels. The first to manifests itself is an increase in the demand for credit, as households and firms experiencing revenue shortfalls draw on their credit lines, often with the support of public guarantees. The increase in the amount of guaranteed credit is revenue-positive for the banks; this explains, for example, why 2020 was a surprisingly good year for small banks in the US[1]Wall Street Journal: “The best year ever: 2020 was surprisingly good to small banks”, 14 December … Continue reading. This positive effect is dampened, and may even be reversed, by the reduction of lending margins which follows from a more accommodative monetary policy. Over time, however, both of these impacts are likely to be dwarfed by the deterioration of credit quality resulting from the recession. This effect becomes evident with a considerable time lag, after the public support measures are lifted.

In the eurozone, an increase in the demand of credit was observed in early 2020. The growth rate of bank loans to non-financial firms, close to 3 percent in the pre-Covid period, rose to 5 percent in the first quarter and reached a plateau around 7 percent in the summer months[2] See ECB Economic Bulletin, various issues.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/ecbu/ecb~b6a4a59998.eb_annex202101.pdf.. Intermediation margins shrunk somewhat, due to the decline of lending rates on certain components of the loan portfolio, mainly overdrafts. By contrast, no deterioration of credit quality has been observed so far in the supervisory statistical reports. The (gross) NPL ratio for the euro area as a whole, slightly over 3 percent at the end of 2019, continued to decline, reaching 2.8 percent in September 2020[3] ECB supervisory statistics,

https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/banking/statistics/html/index.en.html.. However, recent surveys by the ECB suggest that this benign phase may be ending and the post-Covid “wave” of NPLs may now start[4]A. Enria, “European banks in the post-Covid world”, speech given at the Morgan Stanley European Financials Conference, 16 march … Continue reading.

Eventually, NPLs are expected to rise sharply in the eurozone. An estimate based on an adverse scenario, published by the ECB, puts the peak at 1.4 trillion euros[5]A. Enria, “An evolving supervisory response to the pandemic”, Speech given at the European Banking Federation, October 2020; … Continue reading, which would imply a CET1 ratio depletion of up to 5.7 percent. It is interesting to compare this estimate with the NPL increase observed after the great financial crisis (GFC). Between 2007, the last pre-crisis year, and 2013, the peak year, the NPL ratio in the euro area rose by roughly 6 percentage points, while NPLs in nominal terms increased by over 600 bn. euros. If one makes the milder assumption that NPL may rise up to 1 tn. euros, the increase relative to today’s level would be comparable in magnitude to that occurred after the GFC. Under the aforementioned adverse scenario, it would be significantly greater.

While magnitudes may be comparable, the context in which the NPLs increase occurs this time is completely different. In the GFC, the epicenter of the crisis were the banks themselves – their excessive risk taking in the earlier period and later the delays in recognizing the problem and dealing with it. Now, the banks are “victims” of an exogenous and unpredicted shock, which they are in fact contributing to mitigate. As Augustin Carstens, general manager of the BIS, put it at an early stage, banks this time are part of the solution, not of the problem[6]A. Carstens, “Bold steps to pump coronavirus rescue funds down the last mile”, Financial Times, 29

March 2020.. And they have in fact already started doing so, by keeping credit channels open. Supervisory and regulatory measures to deal with the problem should accordingly be different.

Broadly speaking, four were the main areas of response of eurozone supervisors and regulators after the GFC, in dealing with NPLs:

- Supervisory action by the ECB. ECB action was organized in a specific action plan, which included guidelines, regular and ad-hoc reviews and inspections, as well as guidelines and Pillar II requirements applied to capital and provisions;

- Pillar I provisioning requirements. These requirements, embodied in EU law in 2019, are often referred to as “calendar provisioning”;

- Accounting rules. They relate to the way in which NPLs are quantified for accounting purposes, and were introduced in the EU as part of the new IFRS9 framework;

- Asset management companies (AMCs). Various proposals were made to establish AMCs either at national or at area-wide level, to help banks remove NPLs from their balance sheets. These proposals were extensively discussed but never implemented.

In the following sections, these areas are examined from the viewpoint of whether they can help in the new situation. The conclusion is that the two main new regulatory elements which were introduced, points 2 and 3, are no longer suited or at least would require significant adaptation. Asset management companies, at national or at area-wide level, are an interesting avenue to consider but for several reasons are not likely to become part of a realistic policy package in the foreseeable future. Traditional micro-supervisory tools will therefore continue to occupy center stage. The final section expands on this conclusion with some comments on how the ECB can overcome the challenge.

1. Supervisory action

ECB supervision started dealing with NPLs immediately after its inception, in 2014. It did so by launching a dedicated “action plan”, which was started in 2015 and virtually completed, except for routine follow-ups, before Covid struck at the beginning of 2020. Details on the ECB NPL action plan are available from several sources[7]ECB Guidance on Non-Performing Loans, 2017; see https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/guidance_on_npl.en.pdf; and I. Angeloni, Beyond the pandemic: reviving Europe’s banking union; … Continue reading. For our purpose here, three aspects need highlighting.

First, the plan put major emphasis on the need for banks to maintain efficient structures to measure and monitor the state of their exposures and the debtors’ ability to pay. These structures would include ad-hoc internal units able to collect all relevant information, with direct access to top management and decision-making boards. Before the ECB action plan, this was not regarded as a priority by many banks. Often, information on credit quality was not available in a systematic way and therefore boards and management were not always properly informed. As part of the action plan, the ECB requested banks to set up dedicated units in charge of monitoring loan performance, with direct reporting lines to the board, responsible also for proposing solutions for NPL disposal if needed.

This aspect remains crucial today; in fact, good internal information and governance are going to be particularly important in the post-Covid scenario. While bank exposures are provisionally protected by moratoria and guarantees, banks need to continue to maintain an updated picture of the clients’ ability to pay. This is an aspect the ECB supervision has repeatedly insisted on in 2020. Using the earlier metaphor, maintaining good internal information will lower the probability of bad surprises when the “hood of the car” will be opened.

Secondly, the ECB action plan was based on the idea that the NPL strategies should be tailored to the specific conditions of each bank. For this purpose, emphasis was placed on a constant dialogue between the teams of examiners and the bank. Their interaction would exploit the best information available on the situation of the bank’s loan portfolio, in order to propose to the bank’s decision makers and to the supervisory authority itself, the strategy most appropriate in each case.

Third, while tailored to the bank’s specific condition, the NPL strategies should also satisfy criteria common across all supervised banks. Consistent criteria fulfil the banking union’s principle of a single supervisory concept applied to all participating banks. Criteria should be not only consistent, but also transparent. Transparency, a universal principle of good governance, is also a contributor to effectiveness because policies which are well understood tend to be more easily accepted and followed.

The ECB meant to fulfil the twin requirement of consistency and transparency by announcing “supervisory expectations” regarding NPL provisioning. Banks with a significant NPL problem were asked to set-up provisioning plans within specific time frames, different across loan types. “Supervisory expectation” were not rigid rules but rather starting points of supervisory dialogues, during which specific elements could be taken on board and modifications in the provisioning calendar could be made. NPL strategies would eventually become an input in the annual supervisory reviews (Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process, or SREP[8]See https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/about/ssmexplained/html/srep.en.html ), thereby contributing to the determination of Pillar II requirements.

This combination of general criteria and bespoke elements helped exert the right amount of supervisory pressure while not losing sight of individual considerations. This approach was successful: the (gross) NPL ratio for the euro area declined between 2013 and 2019 from close to 7 percent to close to 3 percent, with a marked convergence across countries. The plan and the recapitalization processes that followed did not prevent, in that period, a restart of the bank lending process in the eurozone and a recovery of its economy.

After the pandemic, the SREP was essentially suspended. Pillar II requirements have been kept constant except for a few specific cases. This means that the underlying conditions of the banks’ exposures are no longer reflected in supervisory policies. However, the underlying approach with its blend of rule-based and ad-hoc elements remains valid; in fact, it will be particularly useful during the exit from the pandemic. At that time, bank specific conditions will be particularly important because each bank is impacted differently by the virus and the lockdowns depending on the sectoral and geographical mix of its exposures. The quantum of discretionary decisions by the supervisor is likely to increase. This raises the bar for the ECB, which will need to apply in each case the proper mix of flexibility and determination. Common principles regarding NPL disposal and provisioning plans will remain useful but will require adaptation to individual circumstances. Excessively rigid instruments (like the legal provisioning calendars discussed in the next section) are not going to be helpful.

2. Calendar provisioning

The concept of “supervisory expectation” mentioned in the previous section was initially not universally well understood. While parts of the banking community and some member countries were resisting the ECB’s pressure towards cleaning balance sheets, the European Parliament objected on the legal side, arguing that supervisory expectations invaded the prerogative of legislators by being akin to general rules rather than specific risk-based requirements applied on a case-by-case basis[9]See letter sent to the ECB by the President of the EP on .. 2017 ( See https://www.politico.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2017/10/Letter-to-President-Draghi.pdf). .

Misunderstandings and criticisms converged in putting in motion a process leading to a legislative package dealing with NPLs, which after a long gestation entered into force in 2019[10]See a Council summary here https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/pressreleases/2019/04/09/council-adopts-reform-of-capital-requirements-for-banks-non-performing-loans/. The full text is here … Continue reading . The law prescribed minimum legal coverage levels for loans (so-called “prudential backstops”), with percentages increasing with the time of non-performance (between 1 and 10 years), distinguishing among different loan categories: secured by immovable collateral, secured by movable collateral, and unsecured. The legal (Pillar I) requirement was intended to coexist with possible additional requirements set by the supervisor as part of Pillar II.

Unlike the “expectations”, however, the legal requirement lacked any flexibility in responding to bank specific conditions. This may have been unfit to individual banks in some cases. More seriously, it could become inapplicable to the system as a whole in case of system-wide adverse shocks outside the banks’ control – for example: a pandemic like Covid-19. Not surprisingly, the prudential backstops were de-facto suspended as a result of the entry into force of moratoria and government guarantees[11]The EU “banking package” introduced in 2020 is available here

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_757.

Even beyond the short term, the prospect of restoring the “prudential backstop” in its present form after the pandemic is questionable. Provisioning calendars enshrined in law may at times become an alibis discouraging supervisors from proactively applying Pillar II powers for the same purpose. Parameters set by law across the board, as already mentioned, may not fit individual circumstances. More seriously, in presence of certain shocks they become impossible to apply. Rules whose application is impeded by circumstances difficult to foreseen in advance lose credibility, especially when such circumstances occur.

3. Accounting treatmentof NPLs

As part of the reforms undertaken globally after the GFC, accounting rules for financial institutions were changed in several respects, with the aim of making financial statements responsive to changing economic conditions. Part of the amendments regarded NPLs. The underlying logic there was to make NPL recognition and provisioning no longer based on incurred (past) losses, but rather corresponding more closely to the moment in which the corresponding risks were undertaken.

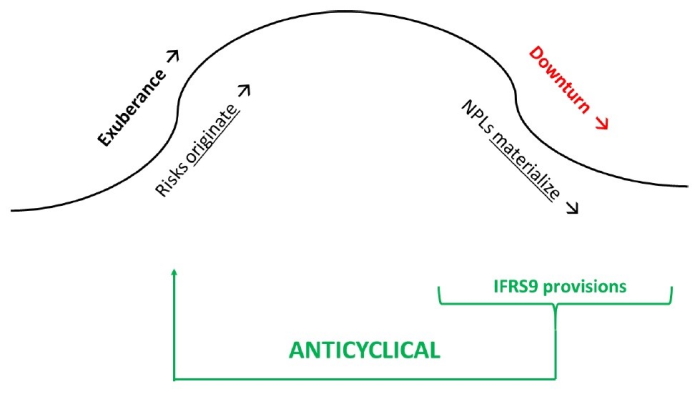

Fig. 1 provides a graphical representation. During normal demand-driven business cycles, risks are perceived to be low in the upswing. In this phase banks tend to undertake more risky lending (left-hand part of the curve), which normally results in NPLs later in time. If provisions are based on incurred losses, they end-up being made when the economy declines (right-hand side of the curve), hence strengthening the recession. It may then be appropriate to anticipate the provisions to match the time when risks originate. Early provisioning dampens growth in booms and stimulates it downswings. Basing provisions on the expected level of NPLs therefore exerts a desirable counter-cyclical effect.

Figure 1: Demand cycle

Following this type considerations, and consistent with the general move towards mark-to-market accounting after the crisis, new IRFS9 rules were introduced in EU law in 2016[12] Commission Regulation 2016/2067; see https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32016R2067, effective in 2018 but with a gradual transition which foresaw a full phasing in only in 2023.

The new approach has two problems. First, it requires banks to formulate accurate expectations of their future losses. This may not be easy, not only because of the inherent uncertainty but because, as already noted, expectations tend to be optimistic in booms and pessimistic in busts[13]See for example J. Abad and J. Suarez, “IFRS 9 and COVID-19: Delay and freeze the transitional arrangements clock“; VoxEU 2 April 2020, see … Continue reading. The second, more serious problem is that the logic just described applies only under the specific demand-driven cycle depicted in fig. 1.

Fig 2 represents a different economic cycle, more similar to that occurred under Covis-19. The left side of the curve represents the time when the pandemic hits the economy with the related initial lockdowns; say, the first half of 2020. The wave of NPL is not yet manifest in that phase; it will occur later. If provisions are based on expected losses, they tend to worsen the economic cycle when it is already declining due to the pandemic shock. It is better, in this case, to delay the provisioning to a later time when the economy recovers (right side of the curve). Under this type of cyclical pattern, unlike in the previous one, traditional, backward looking NPL provisioning based on incurred losses is counter-cyclical, while that stemming from the new accounting rules is pro-cyclical.

Figure 2: COVID-19 Cycle

In 2020, the transitional regime of IFRS9 was further prolonged to take this into account. De-facto, its implementation was suspended. Once again, unexpected circumstances required suspending application of an element of the post-GFC reform program right after it was adopted.

As for the case of calendar provisioning, whether the IFRS9 rules for NPLs can be revived as such after the pandemic is questionable. The new rules are inherently fragile because of the uncertainty of loss expectations. Even abstracting from that, undesired effects arise in a variety of circumstances, as soon as one departs from the textbook case of demand-driven cycles. Well-functioning accounting rules for NPLs need to be designed in a way to respond appropriately in all circumstances, so as to be robust from a macro-prudential perspective. This is a complex question, requiring further analyses which go well beyond the limited scope of this paper.

4. Asset management companies

The idea of removing NPLs from eurozone banks and relegating them in an area-wide AMC was suggested while the ECB was still in the early phases of its NPL action plan. Though an AMC does not in itself necessarily involve mutualization of bank risks (this depends on how the scheme is designed), the proposal immediately faced opposition from some eurozone members, fearing that the proposal would allow countries with large amounts of legacy assets, preceding the launch of the single supervision, to offload part of the burden onto others.

In 2018 the Commission, fulfilling a mandate given by the Council, issued a “blueprint” with criteria for member countries willing to set up their own, national AMCs[14] See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=SWD:2018:72:FIN. The document spelled out conditions for creating such schemes, making suggestions on various aspects including accounting, risk management, transfer pricing, impact on public finances and so on. The blueprint raised interest but as such was not applied, for several reasons. First, no explicit relaxation of state-aid criteria was included in the scheme, thereby limiting its feasibility for countries facing public finance constraints (countries with public finance problems often have also high NPL levels). Second, in the meantime the ECB supervision had advanced in its NPL action plan, and a more active secondary market for NPLs had developed. This allowed several banks in high-NPL countries to conclude important offload operations, alleviating the problem in the countries concerned. In the background, there was also a perception of stigma annexed to national AMCs, whose creation may in itself signal a systemic fragility in the banking sector of the country in question.

The eurozone-wide AMC proposal was revived in 2020 by the ECB[15]6 A. Enria, “The EU needs its own ‘bad bank’”; Financial Times, 27 October 2020 and echoed by the European Commission as part of its Covid strategy[16]Coronavirus response: Tackling non-performing loans (NPLs) to enable banks to support EU households and businesses”; 16 December 2020. See … Continue reading. The Commission proposal, however, dropped the idea of an area-wide scheme arguing instead in favor of a “network” of cooperation, of unspecified content, among national AMCs.

These new proposals, while still rather general, are of interest and should be carefully considered. An element in favor of them is that in the situation created by the pandemic the AMC solution is less prone to the criticisms that had plagued the proposal previously. NPLs derived from Covid cannot be regarded as a “legacy” of past errors by bankers or attributed to national supervisors, as had been the case in the past. These NPLs are the result of a common shock which hit all countries and was outside of their control. The underlying logic of the proposal is therefore stronger.

Yet, there are hurdles in this new proposal as well. First and foremost, the entity of the problem is not known. The wave of Covid-related NPLs has not been observed yet; we do not know when it will develop, how large it will be, how it will be distributed across countries and banks. It seems unlikely that such scheme can be agreed upon, let alone implemented, before this information is available.

Second, certain obstacles faced by the earlier proposals persist, to some extent. Even before Covid, an NPL problem still existed in certain countries and banks. Distinguishing between new, Covid-related losses and the preceding ones may not be easy in all cases. As a result, the objections raised in the past with reference to “legacy” problems may resurface. In addition, the “stigma” effect may still discourage certain countries from setting-up national schemes. The set-up of national “bad banks” could be regarded as a sign of underperformance in a broader sense, not only in dealing with banks including but also in the way the health situation has been handled or the supports to the economy have been provided.

5. Conclusions

The wave of NPLs expected to develop in the eurozone as a consequence of Covis-19, while perhaps not too different in size from to the one observed after the financial crisis, is different in nature and will therefore require different remedies. Predictions are premature, because the phenomenon has not been observed yet. But it is already possible to make some reasoned conjectures on whether the regulatory tools put in place after the earlier crisis are going to be helpful in the new situation.

The two main regulatory instruments introduced before the pandemic in the eurozone’s Pillar I structure for tackling the NPL problem, namely, the so-called “calendar provisioning” and the new accounting principles based on expected losses, are not suitable to deal with the new situation. Even prospectively, after the pandemic will be overcome, their usefulness in their present form is questionable, because either they are excessively rigid, or excessively sensitive to uncertainty, or both. Conversely, the proposals to create AMCs, at national or supranational level, are valid but cannot be seriously considered before the dimension of the post-Covid NPL problem is known.

Absent these, traditional micro-supervisory instruments will continue to play a key role. One more time, the responsibility of cleaning eurozone banks from their NPLs will be predominantly fall on ECB supervision. Pillar II powers will have to be applied flexibly, depending on the conditions of individual banks. But when the moment comes, supervisory pressure should be exerted with determination, using all the independent power that the law and the statutes accord to the single supervision. Not an easy task; but the ECB has the instruments and the expertise necessary to carry it out.

Notes

This draft is based on an intervention made on 11 February 2021 at the Global Annual Conference organized by the European Banking Institute in Frankfurt.

Footnotes