Authors

Olivier Darmouni[1]Associate Professor, Columbia Business School. and Kerry Y. Siani[2]Ph.D. Candidate in Finance and Economics, Columbia Business School.

Abstract

Corporate bonds and bank loans are the two main sources of credit for large firms. Economic theory and practice have shown that they are quite different, and thus that debt composition has implications for firms, the macroeconomy and economic policy. In this article, we map out some key trends in corporate bond issuance and bank lending in the United States and discuss how the COVID shock in 2020 affected firms and credit markets. We draw some comparisons with Europe as well as some implications for policymakers.

1. Bond Issuance vs. Bank Lending

A first important fact is the striking difference in firms’ debt composition between the United States and Europe. Langfield and Pagano (2016) refer to this difference as a European “bank bias.” In general, U.S. firms are much more reliant on market financing and bonds relative to European firms of the same size. Using micro-data from public firms, Darmouni and Papoutsi (2021) estimate that the bond share of corporate credit is roughly twice as large in the United States. For instance, in 2009, bonds represent 35% of U.S. firm’s total debt, relative to only 13% in the Euro Area. Accordingly, it is appropriate to label the European financial system as ‘bank-based’ and the American as ‘market based’. While the reason for this long-standing gap is complex, differences in institutions are often deemed to play an important role. De Fiore and Uhlig (2011) cite differences in the informational environment. Becker and Josephson (2016) emphasize differences in insolvency resolution; the existence of Chapter 11 bankruptcy tilting the scale in favors of bonds in the United States.

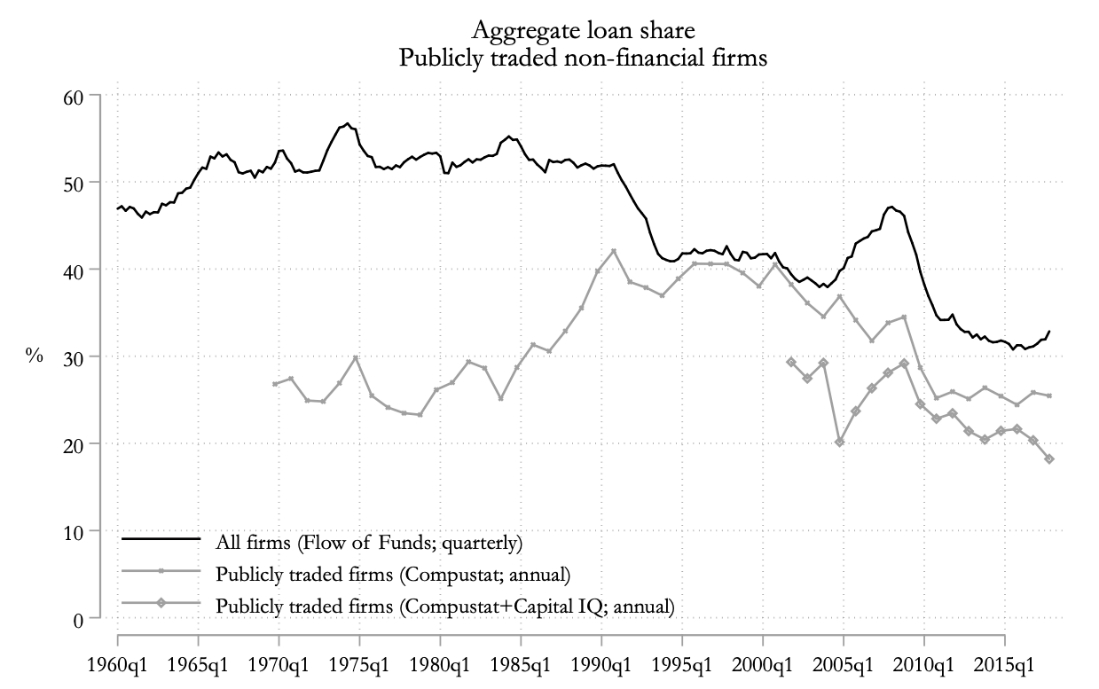

However, this fact should not suggest that this picture is static. Firms rely on both sources of financing, and the relative share of bonds vs. bank loans has changed over time. Berg, Saunders and Steffen (2020) provide evidence that bond financing has grown in the recent decade in the United States, even though it started at a relatively high level relative to Europe. They estimate that bond financing has grown from 17% of GDP in 2008 to 21% of GDP in 2019. Crouzet (2021) finds similar trends using a variety of data sources, as shown in Figure 1. Stricter bank regulation and loose monetary policy likely played a role in this trend. Mota (2020) also highlights the role of a growing demand for safe assets, Grosse-Rueschkamp (2021) of universal banks. Note however that the growth in bond financing has been even larger in Europe, implying a reduction in the loan-bond gap in recent years (Darmouni and Papoutsi, 2021).

Figure 1: Aggregate loan share relative to bonds in the United States

Source: N. Crouzet, “Credit disintermediation and monetary policy.” IMF Economic Review (2021): 1-67.

What are the implications of corporate debt composition for firms? It is well understood that bank lending and market financing are not perfect substitutes. A central aspect of this difference is that loans are made through banking relationships, while bond financing is done at ‘arm’s length’. Relationships allows for monitoring and screening, while bond investors tend to rely on public information like credit ratings (Holmstrom and Tirole, 1997). In addition, relationship lending allows for the potential renegotiation of the terms of credit, while there is much less flexibility in bond financing (Bolton and Scharfstein, 1996). A key implication of this difference is that firms with more bonds have a larger cost of financial distress in bad times. The reason is that bonds tend to be widely held by a dispersed base of investors, which makes them harder to renegotiate. This coordination (free rider) problem across bond creditors means that market financing is typically seen as less reliable in bad times compared to relationship lending from banks.

The firm’s decision to issue bonds as opposed to getting a bank loan is often viewed as a trade-off between growth and risk. The bond market can offer significantly larger amounts and longer maturities than banks, allowing firms to make big, long-term investments. However, this additional capacity has a potential cost if the borrower faces a negative shock that impairs its ability to service its debt. This is especially true in case of recessions that do not originate from the banking sector, such as the COVID-driven recession of 2020. The growth in bond financing has indeed been associated with a shift towards higher risk. For instance, the BBB-rated segment (one notch above the Investment Grade rating threshold) has been growing the fastest in recent years. In Europe, Darmouni and Papoutsi (2021) shows that new bond issuers tend to be smaller, more levered, and less profitable relative to historical issuers.

Will bank lending eventually be replaced by bond financing for large firms? This should not be case, because bonds cannot replace one key role of banks: the provision of liquidity on demand. Indeed, credit plays a dual role: a firm can borrow to finance a long-term investment that will pay off in the future (term lending); or borrow to withstand temporary cash-flow shocks (liquidity provision). Bank-issued credit lines are the corporate analog to households’ credit cards: firms have an available balance that they can draw when they need to and repay when able to. Banks thus have a special advantage in liquidity provision; there is no market substitute that provides liquidity on demand, even in the U.S.

Why are banks unique in providing liquidity? The main explanation is related to banks’ deposit-taking activities. Gatev and Strahan (2006) argue that funds tend to flow towards safe bank deposits in bad times because of a ‘flight-to-safety’ effect. Thus, banks are flush with liquidity precisely in times when firms need funds the most. Kashyap, Rajan and Stein (2002) relatedly argue that banks have an incentive to hoard liquid assets to meet potential deposit outflows, and that these liquid assets can also be used to meet drawdowns on credit lines. Another line of argument is given by Holmstrom and Tirole (1998), which show that credit lines set up in advance can alleviate financial frictions through a liquidity insurance mechanism. In contrast, the bond market, by its very nature, cannot provide funds in advance.

Bank credit lines account for a significant portion of firms’ access to credit. Large U.S. firms maintain sizeable credit lines with banks even if most of their term funding comes from the bond market (Sufi, 2009; Greenwald et al. 2020). The importance of credit lines has been growing in the recent years following the financial crisis (Berg et al., 2020). Notably, credit lines have grown while bonds have crowded out bank term lending. The common view is that banks are still central to corporate credit markets, but that their role has shifted towards providing relatively more liquidity provision in the form of undrawn credit lines, rather than term lending in the form of term loans.

These pre-2020 facts lead to natural predictions about the effects of a large aggregate shock on corporate credit markets. In the absence of a banking crisis, bank loans should take precedence over bonds. Specifically, bank credit lines should play a very special role in providing liquidity to firms. In contrast, the bond market should be suppressed due the lack of profitable investment opportunities and greater risk aversion in market participants. The next section compares these predictions with patterns of loans and bonds issuance in 2020.

2. The COVID Shock: Liquidity-Driven Bond Issuance and the Federal Reserve Response

The spread of COVID led to a large drop in corporate cash-flows in spring 2020. There was a widespread “dash for cash” across the corporate sector as firms scrambled for liquidity (Acharya and Steffen, 2020a; Li et al., 2020). This episode raises many questions: what is the role of the bond market in providing liquidity in bad times? What form of debt do firms prefer to raise to meet their emergency liquidity needs? What are the implications for monetary policy and the real economy?

The COVID period is particularly useful to study the firm’s side of the equation, as neither the supply of bond capital nor bank capital was severely constrained. The bond market lent extensively to firms in this period, a surge that was partly due to a spectacular change in the Federal Reserve credit policy that supported the corporate bond market directly for the first time.[3]See for example Haddad et al. (2020), Boyarchenko et al. (2020), Kargar et al. (2020), O’Hara and Zhou (2020), Gilgricht et al. (2020) or Liang (2020). Both investment-grade (IG) and high-yield (HY) markets reached historical heights in the post-March 2020 period. Figure 2 shows that, as of end of May 2020, investment grade (high yield) issuance by reached $500 billion ($110 billion), compared to $200 billion ($89 billion) over the same period last year.[4]The sample includes U.S. firms and firms that issue in USD and report financial statements in USD.

Figure 2: Bond issuance in 2020

Source: Darmouni and Siani (2020). Data from Mergent FISD, http://bv.mergent.com/view/scripts/MyMOL/index.php, retrieved July 30, 2020.

Note: Red lines correspond to March 23, 2020 (first Fed announcement to buy corporate bonds); April 9, 2020 (first Fed announcement to buy high yield corporate bonds); and May 12, 2020 (start of Fed bond buying program).

How did firms choose to use the bond capital that became more available due to policy intervention? How does bond issuance interact with bank financing? To explore these questions, it is necessary to first understand how firms’ balance sheets change around bond issuance. Analyzing balance sheets before and after bond issuance helps inform what firms do with the funds raised from the bond market in bad times vs. normal times. Below, we present a summary of some key facts studied in more detail in Darmouni and Siani (2020).

Borrowing Without Investment

During COVID, firms used the bond market differently than in normal times. First, while in normal times, firms follow an issuance pattern and raise bonds when they have lower cash balances and debt coming due, firms issuing during COVID raise bond capital earlier in their bond financing cycle and have less debt coming due. This fact indicates that bond issuance during this time was not simply due to firms rolling-over bonds as they mature. Firms actively sought to increase their reliance on the bond market.

Second, after issuance, COVID-era issuers are more likely to hoard the proceeds from bond issuances rather than invest in real assets. We find that in normal times, 58% of IG issuers increase non-cash assets by the second quarter following issuance; however, in COVID times, only 18% issuers did. In addition, firms were less likely to payout to equity holders after issuing during COVID. This pattern lends credence to the view that a large share of issuance was “precautionary” and thus unlikely to be immediately reinvested. Chevron, for example, issued $650 million in bonds on March 24th, but cut its 2020 capital spending plan by $4 billion.

The spike in debt issuance in bad times can be explained by recalling the dual role of credit. Liquidity-driven debt issuance spikes because the real recovery is expected to be slow. On the other hand, investment-driven debt issuance is delayed. These bond issuance patterns are drastically different from normal times. The textbook view of bond issuance exclusively financing long-term investment holds only in good times. 2020 has shown that “liquidity-driven” bond issuance can be equally as important as investment-driven issuance.

The Crowding-Out of Bank Loans

One key aspect of the 2020 crisis is that it did not originate in the banking sector. In fact, banks were healthy and entered the year with strong balance sheets, largely because of tighter regulation put in place since the Great Financial Crisis. In fact, according to the Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officers Survey of April 2020, less than 10% of banks cited capital or liquidity positions as a reason for tightening their lending standards. This is important to frame predictions: the common view would suggest that banks provided most of the funding relative to the bond market. Indeed, while firms issued bonds in the GFC, the main interpretation is that loan supply was restricted after a banking crisis (Becker and Ivashina, 2014).

However, even though the shock did not originate in the banking sector, bond issuance crowded out bank loans in 2020, in two ways.

First, many firms left their existing credit lines untouched while issuing bonds instead. For instance, CVS had $6 billion of its credit line available at the beginning of 2020, yet it still issued $4 billion in BBB-rated bonds. Strikingly, this behavior includes many riskier HY firms: almost 40% of HY issuers received no new net bank funding between January and March. Only 21% had maxed out their credit line by end of March, and the average draw-down rate was below 50%. Many of these riskier firms had available “dry powder” from banks, arranged before the crisis, that they did not use. The pattern is even stronger for IG firms, which represent the bulk of issuance in this period, with over 60% not drawing on their existing credit lines. In aggregate, the amount of undrawn bank credit available at the beginning of 2020 was larger than the total funds raised from bond issuance. HY issuers in our matched sample issued $90 billion in bonds while having $142 billions of undrawn credit available. The gap is even larger for IG issuers.

Second, a large share of issuers that did borrow from their bank early in the crisis repaid by issuing a bond in the following weeks. For example, Kraft Heinz, which was downgraded from IG to junk in February 2020, drew $4 billion from its credit line between February and March. In May, it issued $3.5 billion in bonds (up from a planned $1.5 billion, due to strong investor demand) and used these funds to repay its credit line. In six months, the share of Kraft’s credit coming from banks went from zero to 12% and then back to zero. We find that Kraft is far from an isolated example: among HY issuers repaying bank loans, the median firm paid back 100% of its Q1 borrowing, representing 60% of their bond issuance. In aggregate, a full quarter of HY firms’ bond proceeds went to pay back bank loans. The pattern is similar for IG firms, although a smaller share drew on their credit lines in the first place. We estimate that at least $70 billion was repaid by bond issuers to banks between April and July 2020. Moreover, the majority of the Federal Reserve single-name corporate bond portfolio consists of issuers that had access to bank funds which they did not draw.[5]Based on Federal Reserve portfolio as of July 31, 2020, as reported on August 10, 2020. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/smccf.htm

Figure 3: Credit lines draw-downs in 2020 Q1 vs. Q2

Source: Darmouni and Siani (2020). Based on Capital IQ Capital Structure Summary table, separately by high-yield and investment grade issuers. For ease of interpretation, the figure also displays the negative 45-degree line (exact repayment in Q2) and horizontal line (no change in credit line in Q2). Excludes large outliers Volkswagen, Ford, and GM.

Why would firms prefer issuing bonds over drawing on credit lines in spite of the prediction of common wisdom? There are at least two reasons why this was the case in the spring of 2020.

First, bond financing is more committed for a long period of time: it typically has a longer maturity and no maintenance covenants that banks can use to renegotiate credit (Sufi, 2009). This is attractive because recessions typically imply cash-flow shocks that last for as long as a few years, and firms that need to cover operational fixed costs thus prefer sources of funds that are committed for a longer period. This implies a more nuanced perspective on the value of bank “flexibility” relative to market financing.

Second, the spectacular reversal of the Federal Reserve credit policy has at least partially eliminated one key aspect of banks’ specialness: the implicit and explicit government support they receive. This support implies that banks are viewed as a safe haven by investors, enhancing their willingness to hold deposits in bad times (Gatev and Strahan, 2006). Historically, the corporate bond market has been outside the scope of government support, but this has changed in dramatic fashion in Spring 2020. Correspondingly, investor demand for bonds was sufficiently strong during the COVID episode to finance record levels of issuance in April and May 2020. Moreover, while Falato et al. (2020) document unprecedented outflows from corporate bond funds in March and early April, the phenomenon was short-lived. Following the Federal Reserve’s announced intent to support corporate bond markets on April 9, there were significant net inflows to both HY and IG bond funds that remained very large through August.

Implications for Monetary Policy

Our findings have important implications for the conduct of monetary policy. In particular, direct support for the corporate bond market has received a lot of attention, with many open questions. Our evidence shows that it is important to account for the crowding out of bank loans when evaluating the aggregate effects of these new public programs on the real economy. For the majority of issuers, propping up bond markets does not alleviate a hard credit constraint, since they already have available bank funding. Moreover, firms by and large did not re-inject the record amount of bond issuance into their operations: they instead hoarded most of it in cash on their balance sheet or repaid existing debt. This evidence suggests that the V-shaped recovery of bond markets, propelled by the Federal Reserve, is unlikely to lead to a V-shaped recovery in real activity.

Preventing large bank credit line drawdowns is nevertheless valuable for at least three reasons: (1) it guarantees a longer-term funding source for firms, (2) it helps weaker issuers to “keep their powder dry” to weather any further negative shocks, and (3) it reduces balance sheet constraints on banks (Acharya and Steffen, 2020b). However, as of now, there is little evidence that corporate bond purchases have “trickled down” to smaller borrowers. In fact, it seemed that small firms were largely unable to borrow from banks during the spring of 2020 (Chodorow-Reich et al., 2020, Greenwald et al., 2020). Moreover, the benefits of supporting the bond market directly by extending lender of last resort policies beyond the banking sector must be balanced against potential losses on central bank bond holdings or asset price distortions leading to excessive risk-taking.

References

Acharya, V.V., and Steffen, S (2020b). The risk of being a fallen angel and the corporate dash for cash in the midst of covid. CEPR COVID Economics, 10, 2020b.

Acharya, V.V., and Steffen, S. (2020a). ‘Stress tests’ for banks as liquidity insurers in a time of covid. VoxEU.org, (March 22, 2020a).

Becker, B., and Ivashina, V. (2014). Cyclicality of credit supply: Firm level evidence. Journal of Monetary Economics, 62, 76-93.

Becker, B., and Josephson, J. (2016). Insolvency resolution and the missing high-yield bond markets. The Review of Financial Studies, 29 (10), 2814-2849.

Berg, T. Saunders, A., and Steffen, S. (2020). Trends in Corporate Borrowing. Annual Review of Financial Economics.

Bolton, P., and Scharfstein, D.S. (1996). Optimal debt structure and the number of creditors. Journal of Political Economy, 104 (1), 1-25.

Boyarchenko, N., Kovner, A.T., and Shachar, O. (2020). It’s what you say and what you buy: A holistic evaluation of the corporate credit facilities.

Chodorow-Reich, G., Darmouni, O., Luck, S., and Plosser, M. (2020). Bank liquidity provision across the firm size distribution. Working Paper.

Crouzet, N. (2021). Credit disintermediation and monetary policy. IMF Economic Review, 1-67.

Darmouni, O. and Papoutsi, M. (2021). The Rise of Bond Financing in Europe. Working Paper.

Darmouni, O., and Siani, K. (2020). Crowding-Out Bank Loans: Liquidity-Driven Bond Issuance. CEPR COVID Economics, 51, (October 2020).

De Fiore, F., and Uhlig, H. (2011). Bank finance versus bond finance. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 43 (7), 1399-1421.

Falato, A., Goldstein, I., and Hortaçsu, A. (2020). Financial fragility in the covid-19 crisis: The case of investment funds in corporate bond markets. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gatev, E., and Strahan, P.E. (2006). Banks’ advantage in hedging liquidity risk: Theory and evidence from the commercial paper market. The Journal of Finance, 61 (2), 867-892.

Greenwald, D.L., Krainer, J., and Paul, P. (2020). The credit line channel. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Grosse-Rueschkamp. (2021). Universal banks and firms debt structure, Working Paper.

Haddad, V., Moreira, A., and Muir, T. (2020). When selling becomes viral: Disruptions in debt markets in the covid-19 crisis and the Fed’s response. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Holmstrom, B., and Tirole, J. (1997). Financial intermediation, loanable funds, and the real sector. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112 (3), 663-691.

Kargar, M., Lester, B.T., Lindsay, D., Liu, S., and Weill, P.O. (2020). Corporate bond liquidity during the covid-19 crisis. Covid Economics, 27, 31-47. Kashyap, A.K., Rajan, R., and Stein, J.C (2002). Banks as liquidity providers: An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit‐taking. The Journal of Finance, 57 (1), 33-73.

Langfield, S., and Pagano, M. (2016). Bank bias in Europe: effects on systemic risk and growth. Economic Policy, 31 (85), 51-106.

Li, L., Strahan, P.E., and Zhang, S. (2020). Banks as lenders of first resort: Evidence from the covid-19 crisis. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies.

Liang, N. (2020). Corporate bond market dysfunction during covid-19 and lessons from the Fed’s response.

Mota, L. (2020). The Corporate Supply of (Quasi-) Safe Assets. Working Paper.

O’Hara, M., and Zhou, X.A. (2020) Anatomy of a liquidity crisis: Corporate bonds in the covid-19 crisis. Available at SSRN 3615155.

Sufi, A. (2009). Bank lines of credit in corporate finance: An empirical analysis. The Review of Financial Studies, 22 (3),1057-1088.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Associate Professor, Columbia Business School. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ph.D. Candidate in Finance and Economics, Columbia Business School. |

| ↑3 | See for example Haddad et al. (2020), Boyarchenko et al. (2020), Kargar et al. (2020), O’Hara and Zhou (2020), Gilgricht et al. (2020) or Liang (2020). |

| ↑4 | The sample includes U.S. firms and firms that issue in USD and report financial statements in USD. |

| ↑5 | Based on Federal Reserve portfolio as of July 31, 2020, as reported on August 10, 2020. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/smccf.htm |