In the aftermath of the crisis, we are dealing with an issue of mismatched demand and supply in SMEs financing, that the traditional lending technologies and actors seem not able to overcome. In this essay, we have summarized the main actors, technologies and informational issues involved in the SMEs financing. On one side, there are the banks who are typically the originators of loans, and follow the traditional banking technology. On the other side, there is the entire investor community, that is made up of new lending entities, like shadow banks, in a broad sense, but also other private and public agents. A solution to the mismatched demand and supply in SMEs financing requires at the same time a diversification both of actors and of technologies used in the financial markets.

1. Introduction

The global financial crisis of 2007-2009 has profoundly affected the business conditions for SMEs, and exacerbated their financial constraints. As a result, funding deficiencies have emerged across European countries, together with low investment and growth. In the aftermath of the crisis, we are dealing with an issue of mismatched demand and supply in SMEs financing, that the traditional lending technologies and actors seem not able to overcome. It is a fact that financial resources dried up for SMEs including in many cases the most dynamic enterprises. It is still unclear where the causes of the problem actually lie: do they lie in the supply or in the demand side of finance? Moreover, is it a transitory issue, i.e. crisis related, that is slowly being resolved over time as the effect of the financial crisis fades, or, rather, a structural one that will persist?

At the same time, markets are gaining ground as a source of finance for European corporates. However, this promising picture characterizes mostly large companies, that can count on a relatively easy access to market finance as an alternative to bank finance. In fact the European corporate sector has in aggregate significantly decreased its level of borrowing and in many countries it is becoming a net provider of funds to the financial system (Giovannini et al. 2015). SMEs are not served by market finance in a manner that is adequate to compensate the lower level of funding provided by banks. Thus, it is especially SMEs that are suffering from a mismatching in supply and demand for financing.

The European corporate structure is dominated by SMEs. In Europe there are 21.3 million firms, employing 88.6 million individuals and producing €3,537 billion of gross value added: they represent the 99.8 per cent of all companies, 67.4 per cent of employment and 58.1 per cent of gross value added (Kraemer-Eis et al. 2013, Giovannini et al. 2015). The size distribution differs across Europe: however, European countries with the highest prevalence of SMEs suffered the most severe economic downturn (Klein 2014). Moreover, the financial position of firms is one of the main determinants of their investment and innovation decisions. European SMEs rely mainly on external finance and most of it is provided by the banking sector. The excessive reliance on bank credit is one of the factors that have made SMEs particularly vulnerable in the aftermath of the crisis.

SMEs financing problems are currently under scrutiny by European policymakers. In February, the European Commission has launched a public consultation on the topic of Capital Markets Union with the aim to support higher integration and promote higher access to funding for SMEs. The Commission released a Green Paper to illustrate the main areas that the consultation sought to address: improving access to financing for all businesses across Europe and investment projects, in particular start-ups, SMEs and long-term projects; increasing and diversifying the sources of funding from investors in the EU and all over the world; and making the markets work more effectively so that the connections between investors and those who need funding are more efficient and effective, both within Member States and cross-border [1]See European Commission (2015).. The Action Plan, released on September 30th, restates as key principles of the entire projects creating more opportunities for investors, connecting financing to the real economy, fostering a stronger and more resilient financial system, deepening financial integration and increasing competition. It also provides some indications about the next initiatives that the Commission wants to promote.[2]In particular, key early actions are new rules on securitisation, new rules on Solvency II treatment of infrastructure projects, public consultation on venture capital, public consultation on covered … Continue reading

In a recent survey, the OECD have monitored SMEs’ and entrepreneurs’ access to finance in 34 countries over the period 2007-13 to evaluate their financing needs and whether they are being met or not. [3]See OECD (2015). Three of their findings are particularly interesting. First, they found that access to finance to SMEs is still constrained by the dismal macroeconomic performance and bank deleveraging, leaving SMEs with fewer alternatives available than large firms. Second, they noticed that there is also a potential drop in demand of credit by SMEs even in presence of eased credit conditions. Third, non-bank finance instruments are gaining ground but still cannot compensate for a retrenchment in bank lending, in spite of the various government initiatives pushing in that direction. These three findings reflect three different elements of the problem of mismatched demand and supply in SMEs financing: actors involved, information and technology.

2. Actors, information and technology for SMEs’ financing

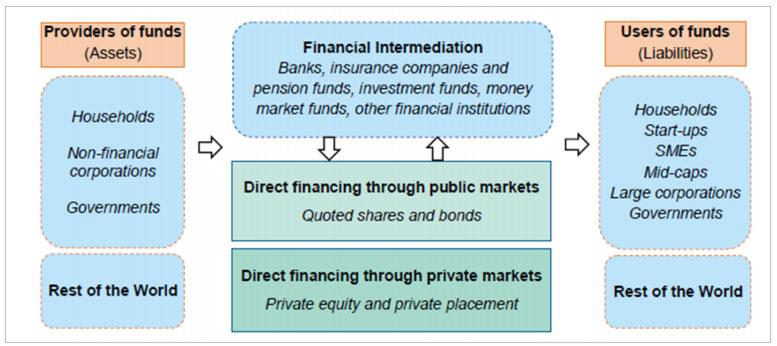

Who are the actors in the marketplace for SMEs’ financing? On one side, there are the banks who are the originators of loans, and follow the traditional banking technology. On the other side, there is the entire investor community, that is made up of new lending entities, like shadow banks, in a broad sense, but also other private and public agents. Given that SMEs’ financing is particularly fragmented and diverse, who could be the most efficient actor providing for SMEs financing? The chart in Figure 1 represents a stylized scheme of the flow of funds that happens in the economy and the different actors involved. The matching between financial resources from the providers of funds (e.g., domestic and foreign households, governments, NFC) to the users (e.g., domestic and foreign households, start-ups, SMEs …) is possible through financial markets. The actors that operate on financial markets, in a broad sense, are financial intermediaries, i.e. banks, insurance companies and pension funds, money market funds and other financial institutions, but also other private and public agents, i.e. household, NFC, governments, that can use capital markets. Usually, capital markets financing is also defined as direct financing, since investors and borrowers exchange securities directly, as opposed to indirect financing that takes place through financial intermediaries, mostly banks. With the development of international financial markets and the changing business of banks, banks themselves are becoming investors and borrowers active on capital markets, making the traditional distinction more and more opaque. With the crisis, the entire mechanism, however, has shown its intrinsic fragility at the expenses of some actors. SMEs have been those most affected since they have been credit rationed from the banking side and at the same time did not have the appropriate size and characteristics to look directly for funds on capital markets.

Figure 1. Stylized view of capital markets in the broader financial system

Source: European Commission (2015)

By their very nature, SMEs are less equipped to access public markets. Think for example about the way owners/entrepreneurs manage the finances of their own company: they are in many cases fully integrated with their own personal finances. Using regulatory language, SMEs are more likely to be affected by related party transactions problems than larger corporations. Yet, the main difficulty faced by SMEs in approaching financial markets is the lack of credit information. Information is critical in the functioning of the financial system. Information is one of the fundamental inputs of the financial business. If we think of Robert Merton’s catalogue of the functions of a financial system (provision of payments systems; pooling of funds to undertake large-scale indivisible investments; transfer of economic resources through time and across geographic regions and industries; trading of risk; supply of price and other information to help coordinate decentralized decision-making in various sectors of the economy; development of contractual mechanisms to deal with asymmetric information and incentive problems), every function performed requires appropriate provision of information to the parties involved. [4]See Merton (1995, pp. 23-41) and Giovannini et al. (2015, pp. 59-63). There is a serious information deficiency in financial markets. Technical standards, conventions, regulations and laws do not timely respond to the benefits of technological progress, and reduce incentives of private actors to innovate. This may sound particularly odd when we think how fast information and communication technologies are evolving in the modern economy. However, it causes most of the information inadequacy that affects the structure of the modern financial system.

Is there a better information structure? Access to information involves two aspects: there is an issue about the availability of the information and an issue about the production and comparability cross-border. For example, there are countries in which it is not even mandatory to deposit the balance sheet and countries where it is, or countries where the obligation is not enforced. One of the main challenges in building a well-functioning informational infrastructure is the small size of a majority of corporate borrowers. There are fixed costs of setting up information flows that are adequate and complete to let investors take their decisions. Banks play a critical role in addressing information deficiencies since they owns an invaluable information set about corporate borrowers. Information problems are particularly acute for small borrowers. Larger borrowers, typically public companies, are subject to disclosure requirements, governance rules and other obligations that make collection of information and the assessment of their credit worthiness an easier task. SMEs have little access to securities markets in Europe. Moreover, SMEs’ owners and managers release information to minority shareholders, to the other stakeholders and to the public in general, keeping in mind the goal of maintaining corporate control.

Given the current state of information provision for the purpose of financing of SMEs, there is plenty of room for improvements, and opportunities for innovation. The effects of these improvements and innovations could be to support a market for corporate financing that complements the traditional banking channel. Many reforms have been suggested to improve the quality of information (see, for example, Giovannini and Moran 2013). In Europe, the aggregation of business registers would be an important step further in this direction. Business registers typically examine and store information on the company’s legal form, its seat and its legal representatives, and make it available to the public. SMEs should be required to deposit, for free or at marginal cost, their annual accounts on an electronic support at business registers. Once these data are available and accessible to everyone on an EU wide basis, for free or at marginal costs, investors would potentially be able to address borrowers’ worthiness and take informed investment decisions. Securities markets can function only if investors can rely on liquidity. Liquidity is provided by active trading in secondary markets. Secondary markets need to be well developed to make securities markets an efficient and reasonably convenient investment option. In presence of a myriad of small borrowers, the only solution to let them access securities markets is to aggregate loans to different borrowers in pools that are large enough to sustain an acceptable volume of transactions every day. The aggregation exercise requires reliable and detailed risk information about each individual loan.

According to the traditional technology, banks act as originators of loans. Banking technology is characterized by liquidity management and complementarities between transaction banking and credit business: the bank owns a “window” on the client that allows it to address its worthiness, i.e. the flow of payments of a bank’s client contains information about that client’s economic health. Is today such technology still viable? Are really banks the actors for SMEs? We believe the jury is still out on this question. Banks have undergone very large cost-cutting programs, which have compelled them to reassess corporate lending. Credit assessment is a technology with a significant fixed-cost component: therefore in a cost-cutting exercise small businesses will be rejected ex-ante. We are currently observing a number of cases where banks outsource credit assessment to specialized companies—a model that is far removed to the traditional banking business model. In addition, as shown by the recent global financial crisis, a bank-centred financial system has serious fragilities. Such fragilities are caused by the fact that banks have moved to activities, such as derivatives business and proprietary trading, characterized by high risk/high return profiles. Now however, and especially in Europe, there is growing concern that, despite the presence of banks in securities trading, securities markets are not sufficiently developed. In Europe the size of bank intermediation versus securities intermediation is significantly higher than in the United States, and large parts of the economy, especially SMEs, are excluded from securities financing.

3. Shadow banking and other non-bank sources of SME’s finance

Assuming that the development of capital markets would allow SMEs to access them more easily than today, still, who should take the risk for funding SMEs if not traditional banks? An important issue to consider is certainly shadow banking. There are many views about it and whether it is riskless or not, accessible to anyone or limited to experts and specialists, unregulated or subject to the same safeguards in terms of constraints and regulation of traditional banks. Is it an entity that does liquidity and maturity transformation, exactly like banks? If so, why doesn’t it have the same safeguards?

Shadow banking has been the main culprit of the 2007-2008 financial crises. Yet, it has been overlooked by the regulatory response to the crisis. The name itself might be misleading with respect to the phenomenon under consideration. Commentators started to use the label ‘shadow’ to refer to any financial activity and subject not yet regulated in the American system, as opposed to the highly regulated banking sector. FSB (2013) describes the shadow banking system as “credit intermediation involving entities and activities (fully or partially) outside the regular banking system”, i.e. shadow banking comprises any activity outside banks. As good as a benchmark definition, it still does not entirely capture the described phenomenon, since not all non-bank lending is shadow banking. An alternative ‘functional’ approach (Claessens et al., 2012; Poszar et al., 2010, revised 2012) focuses on the intermediation services provided by the shadow banking system. It defines shadow banking as a collection of activities each of them responding to its own demand factors, such as securitization, collateral services, bank wholesale funding arrangement, deposit-taking and lending by non-banks. However, the list suggested by the functional approach might leave out new future shadow banking activities and it might not capture shadow banking activities in operation in countries other than the US (e.g., lending by insurance companies in Europe or wealth management products in China). The specific combination of repos and securitization, called “securitized banking” (Gorton and Metrick, 2010), is just a part of the broader shadow banking that includes also activities beyond repos and securitization, such as investment banks, money-market mutual funds (MMMFs), and mortgage brokers, sale-and-repurchase agreements (repos), asset-backed securities (ABSs), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP).

Claessens and Ratnovski (2014) suggest a new way to describe shadow banking as “all financial activities, except traditional banking, which require a private or public backstop to operate.” The need for an official backstop is thus key to shadow banking operation. In this view, shadow banking can also be seen as “money market funding of capital market lending” (Mehrling et al., 2013) or activity of issuing very short term money market like instruments and investing the proceeds in longer-term financial assets (Ricks, 2012). These definitions have in common two important characteristics of shadow banking: maturity transformation and the integration of money market (short term wholesale funding) with capital markets (risk pricing and collaterals). The latter emphasizes how shadow banking is a “monetary phenomenon, not just a financial one” (Ricks, 2012), and thus has to be analysed in conjunction with the design of the monetary system. The need for an official backstop is due to the fact that shadow banking activities involve risky maturities transformation, just like traditional banking, through many capital markets mechanisms instead of a single banking balance sheet.

The key point in the definition of shadow banking is the systemic risk that can arise from maturity transformation and the need for a backstop. Only activities that need access to backstop, since they combine risky maturity transformation, low margins and high scale with residual tail risks, are systemically-important shadow banking. Each time a monetary liability redeemable at par is invested in illiquid activities, problems arise once a doubt that there is some secret on the value of the bank (i.e., unknown losses) spread around and generate a run on the shadow banking, in the form, for example, of a sudden stop in banks’ ability to rollover their short term debt. The 2007-2008 financial crises can be considered as a run on shadow banking, that essentially took the form of a run on three types of activities: repos, commercial papers and money market mutual funds (Gorton and Metrick, 2010). Hence, we learned that the official backstop was at the time done through implicit and explicit support from sponsor banks.

The focus of the regulatory debate on financial markets has to move towards the strengthening of oversight and regulation of shadow banking, as FSB (2013, 2014) is suggesting. The main policy challenges are given by the correct identification of shadow banking risks and the importance of preventing shadow banking from accumulating systemic risks through regulation and macro prudential supervision. Such challenges are not outside the regulatory reach as long as regulators can control the ability of regulated entities to use their franchise value to support shadow banking activities, manage government guarantees and reduce the too-big-to-fail problem. With these safeguards in place, shadow banks could also play a role as funding actors for SMEs.

There are also other sources of finance for SMEs that need some attention for their potential evolution. Minibonds are a potential important source of finance for SMEs. In countries like Italy they have been well received, although still of limited size and diffusion. The fact that minibonds cannot be purchased by retail investors (imposition that reflects the regulator’s over-concern of consumer protection) is the main reason of their limited market development. The key feature is a series of softer requirements for issuers and discounts on services like rating. Individual issues are so small that they cannot be considered as instruments tradable in the market, i.e. they are still not liquid enough. Most vehicle investing in minibonds are adopting the policy of holding them until maturity. Hence minibonds are just another legal scheme for arranging private placements. The objective of making SME credit tradable has not, and could not, been met, but the simplification of the issuance process has had some positive effects.

There are also other private initiatives worth mentioning in terms of diversified funding for SMEs. One of the most successful innovations in financing of SMEs, though not through securities markets, is a set of private initiatives that rely on a novel way to gather and manage information: the phenomenon of eFinance, or crowdfunding. The development of social networks and the ease and speed of dissemination of information through the web contribute to its successful implementation. Crowdfunding initiatives offer both debt and equity finance, typically to very small projects that are distributed to large numbers of very small investors. The success of these projects demonstrates that they are filling a real gap in the marketplace especially for SMEs.

4. Conclusions

In this essay, we have summarized the main actors, technologies and informational issues involved in the SMEs financing. On one side, there are the banks that are typically the originators of loans, and follow the traditional banking technology. On the other side, there is the entire investor community, that is made up of new lending entities, like shadow banks, in a broad sense, but also other private and public agents. SMEs’ financing is particularly fragmented and diverse, so it is not obvious who could be the most efficient actor providing for SMEs financing. Similarly, it is not clear what should be the most efficient technology and informational infrastructure. A solution to the mismatched demand and supply in SMEs financing requires at the same time a diversification both of actors and of technologies used in the financial markets. The effects of the mismatching in demand and supply in SMEs financing have certainly been exacerbated by the financial crisis. However, there are many issues that are structural in nature and need to be adequately addressed. We believe banks will still play an important role in SMEs funding; this will require a streamline in their business model. An important role for the public authorities is the creation of an informational infrastructure that is widely recognized as the missing element for the development of an efficient SMEs financing. At the same time, more incentives should be introduced in order to further develop all those market and private initiatives for micro lending.

References

Adrian, T., Ashcraft, A.B., and Cetorelli, N., 2013. Shadow Bank Monitoring. New York Fed Staff Report 638, September.

Claessens, S., Pozsar, Z., Ratnovski, L., and M. Singh, 2012. Shadow Banking: Economics and Policy. IMF Staff Discussion Note 12/12, Washington, D.C.

Claessens, S., and Ratnovski, L., 2014. What is Shadow Banking? IMF Working Paper 14/25.

European Commission, 2015. Building a Capital Markets Union. COM (2015) 63 final. February 18.

FSB (Financial Stability Board), 2013. Strengthening Oversight and Regulation of Shadow Banking. Policy Framework for Strengthening Oversight and Regulation of Shadow Banking Entities. August 29.

FSB (Financial Stability Board), 2014. Update on financial regulatory factors affecting the supply of long-term investment finance. Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, September 16.

Giovannini, A., Mayer, C., Micossi, S., Di Noia, C., Onado, M., Pagano, M., and Polo, A., 2015. Restarting European Long-Term Investment Finance. A Green Paper Discussion Document. CEPR Press and Assonime, January.

Giovannini, A. and Moran, J., 2013. Finance for Growth. Report of the High Level Expert Group on SME and Infrastructure Financing. December.

Gorton, G. and Metrick, A., 2010. Regulating the Shadow Banking System. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Fall, pages 261-97.

Klein, N., 2014. Small and Medium Size Enterprises, Credit Supply Shocks, and Economic Recovery in Europe. IMF Working Paper No. 14/98, June.

Kraemer-Eis, H., Lang, F., and Gvetadze, S., 2013. Bottlenecks in SME financing. In Investment and Investment Finance in Europe, Luxembourg: EIB.

Mehrling, P., Pozsar, Z., Sweeney, J., and Nielson, D. H., 2013. Bagehot was a Shadow Banker: Shadow Banking, Central Banking, and the Future of Global Finance. November 5, 2013.

Merton, R.C., 1995. A Functional Perspective of Financial Intermediation. Financial Management 24(2), pp. 23 –41.

OECD, 2015. Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2015: An OECD Scoreboard. OECD Publishing, Paris.

Pozsar, Z., Adrian, T., Ashcraft, A., and Boesky, H., 2010, revised 2012. Shadow Banking. New York Fed Staff Report 458.

Ricks, M., 2012. Money and (Shadow) Banking: A Thought Experiment. Review of Banking and Financial Law 731.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | See European Commission (2015). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In particular, key early actions are new rules on securitisation, new rules on Solvency II treatment of infrastructure projects, public consultation on venture capital, public consultation on covered bonds, cumulative impact of financial legislation. |

| ↑3 | See OECD (2015). |

| ↑4 | See Merton (1995, pp. 23-41) and Giovannini et al. (2015, pp. 59-63). |