The Single Market stimulates cross-border banking throughout the European Union. This paper documents the banking linkages between the 9 ‘outs’ and 19 ‘ins’ of the Banking Union. We find that some of the major banks, based in Sweden and Denmark, have substantial banking claims across the Nordic and Baltic region. We also find large banking claims from banks based in the Banking Union to Central Eastern Europe. These findings indicate that these ‘out’ countries could profit from joining the Banking Union, because it would provide a stable arrangement for managing financial stability. From a political perspective, member states’ opinion on joining the Banking Union ranges from an outright “no” towards considering Banking Union membership.

1. The rationale for Banking Union

The decision to initiate Banking Union in June 2012 was a reply to tackle one of the root-causes of the European debt crisis, namely the sovereign-banking loop. The vicious circle between the solvency of nation states in the euro area and the solvency of these nation states’ banks contributed to the crisis. The sovereign-banking loop works in both directions. First, banks carry large amounts of bonds of their own government on their balance sheet (Merler and Pisani-Ferry, 2012; Battistini et al, 2014). So, a deterioration of a government’s credit standing would automatically worsen the solvency of that country’s banks. Second, a worsening of a country’s banking system could worsen the government’s budget because of a potential government financed bank bailout, and because of lower tax revenues due to the subsequent economic downturn (Angeloni and Wolff, 2012). Alter and Schüler (2012) and Erce (2015) provide evidence of interdependence between government and bank credit risk during the crisis.

The sovereign-banking loop argument relates to the euro area, where national central banks have given up the control over the currency in which their debt is issued, putting the European Central Bank (ECB) in charge. To break the loop, a summit of Euro area heads of states and governments decided in June 2012 to move the responsibility for banking supervision to the euro-area level as a pre-condition for direct bank recapitalisation by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Moreover, the ECB was particularly exposed since it was forced to provide liquidity to euro area banks without supervisory control. As pointed out by Goodhart and Schoenmaker (2009), if ex-post rescues are to be organised at the European level, ex-ante supervision should also be moved in tandem to minimise the need for such rescues. The essence of the Banking Union, therefore, is supervision and resolution of banks at the euro-area level.

However, Constâncio (2012) and Schoenmaker (2013) highlight that the deeper rationale for the Banking Union is cross-border banking. The financial trilemma (Schoenmaker, 2011) indicates that the combination of cross-border banking and national supervision and resolution leads to a coordination failure between national authorities, which do not take into account cross-border externalities of their supervisory practices. This coordination failure might in turn result in an under provision of financial stability as a public good. To overcome this financial stability challenge, supranational policies have been adopted. The coordination failure argument is related to the Single Market, which allows unfettered cross-border banking, and thus to the European Union as a whole. Furthermore, the Banking Union encourages further cross-border banking integration and hence reinforces the Single Market, a point raised by Asmussen (2013) and Mersch (2013). The Banking Union could be an advantage for countries outside the euro, which are characterised by a high degree of cross-border banking. The Regulations for the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) state that it is possible to join at a later stage, as participation is mandatory for euro-area member states, and optional for non-euro area European Union members.

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, we aim to provide a theoretical background on policy coordination, followed by an empirical part on the cross-border banking links that characterise both the ‘ins’ and the ‘outs’ in the Banking Union[1]The term ‘outs’ refers to the 9 European Union countries outside Banking Union as of January 2015, namely Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sweden and the … Continue reading. We present evidence of strong banking integration in the Nordic region, where Denmark and Sweden are on the outside and Finland and the Baltics on the inside. It also appears that the vast majority of the large inward banking claims for the ‘outs’ in Central and South Eastern Europe is coming from the Banking Union.

Second, we discuss the pros and cons of joining Banking Union for the ‘outs’. For the connected countries, joining Banking Union would allow for an integrated approach towards supervision (avoiding ring-fencing of activities and therefore a higher cost of funding) and resolution (avoiding coordination failure). Next, the national supervisory and resolution authorities get a seat at the Banking Union table[2]However, a differentiation emerges, as non-euro countries are not members of the ECB’s Governing Council that is charged with adopting supervisory decisions drafted by the Supervisory Board.. In the meantime, countries can preserve the sovereignty over their banking system outside the Banking Union. Nevertheless, the ‘outs’ located in Central Eastern Europe have already partly lost the sovereignty, as they are highly dependent on the Banking Union for their stability.

This paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the potential for coordination failure in international banking. Section 3 provides an overview of the new Banking Union landscape and analyses the inward and outward banking claims of the ‘outs’. It also provides a cost-benefit analysis on joining the Banking Union for the ‘outs’. Section 4 discusses the political state of play in the single member states outside the Banking Union and Section 5 concludes.

2. Theory of policy coordination

Financial stability is a public good. A key issue is whether governments can still provide this pubic good at the national level with today’s globally operating banks. The financial trilemma states that (1) financial stability, (2) international banks and (3) national financial policies are incompatible (Schoenmaker, 2011). Any two of the three objectives can be combined but not all three; one has to give. Figure 1 illustrates the financial trilemma. The financial stability implications of cross-border banking are that international cooperation in banking bailouts is needed.

Figure 1: The financial trilemma

Source: Schoenmaker (2011)

Financial stability is closely related to systemic risk, which is the risk that an event will trigger a loss of economic value or confidence in a substantial portion of the financial system that is serious enough to have significant adverse effects on the real economy. Acharya (2009) defines a financial crisis as systemic if many banks fail together, or if one bank’s failure propagates as a contagion causing the failure of many banks. The joint failure of banks arises from correlation of asset returns and the externality is a reduction in aggregate lending and investment.

The 2007-2009 financial crisis illustrates the financial trilemma, with the handling of Lehman Brothers and Fortis as examples of coordination failures (Claessens, Herring and Schoenmaker, 2010). During the rescue-efforts of Fortis, cooperation between the Belgian and Dutch authorities broke down despite a long-standing relationship in ongoing supervision. Fortis was split along national lines and subsequently resolved by the respective national authorities at a higher overall fiscal cost.

Rodrik (2000) provides a lucid overview of the general working of the trilemma in an international environment. As international economic integration progresses, the policy domain of nation states has to be exercised over a much narrower domain and global federalism will increase (e.g. in the area of trade policy). The alternative is to keep the nation state fully alive at the expense of further integration. The domestic orientation of the financial safety net is a barrier to cross-border banking, as national authorities have limited incentives to bail out an international bank. This is visible in the results of Bertay, Dermirguc-Kunt and Huizinga (2011), who find that an international bank’s cost of funds raised through a foreign subsidiary is higher than the cost of funds raised by a purely domestic bank.

How to solve the financial trilemma? The literature on international policy coordination distinguishes two main strands. The first solution is to develop supranational solutions (Obstfeld, 2009). In this case, national financial policies are replaced by an international approach for supervision and resolution. Participating countries have to share the burden in case of a bank bailout, resulting in a loss of sovereignty, which is politically controversial (Pauly, 2009). The Banking Union members have chosen this approach. The second is to segment national markets through restrictions on cross-border flows (Eichengreen, 1999). In the case of international banks, the segmentation can be done through national regulations, which favour a network of fully self-sufficient, stand-alone national subsidiaries, as opposed to a network of branches (Cerutti et al., 2010). The ‘outs’ have adopted the latter approach, safeguarding national sovereignty.

2.1 Geographical ring fencing

National policies which curb international banking both at the home and in the host country are for example prudential tools such as ring fencing, which separate part of a cross-border banking group from its parent or subsidiaries, on a permanent or temporary basis (D’Hulster and Ötker-Robe, 2015). This geographic segmentation works through constraints on intra-group liquidity and capital movements, thereby decreasing the risk of cross-border contagion. The establishment of a network of fully self-sufficient subsidiaries could be the final outcome of such ring fencing (Schoenmaker, 2013).

Cerutti et al. (2010) provide arguments in favour of and against ring fencing. For a host country supervisor, the decision to impose ring fencing would typically be driven by macro-financial stability considerations, such as the need to protect the domestic banking system from negative spill-overs from the rest of the group. Vice versa, the home country supervisor may wish to limit foreign exposures affecting the parent bank. It may do so by requiring local funding for foreign operations in separately capitalised and funded subsidiaries. The exposure for the parent bank is then limited to the capital invested in the foreign subsidiary, applying the concept of limited liability. Another argument for ring fencing is to limit the exposure of national deposit insurance schemes. While foreign branches would fall under the home country deposit insurance schemes, foreign subsidiaries could participate in the respective host country deposit insurance schemes.

By contrast, the arguments in favour of centralised international bank structures and against ring fencing rely on efficiency and financial stability considerations (for example, benefits of diversification across country-specific shocks). From an international bank’s perspective, the ability to freely reallocate funds across its affiliates is essential for achieving the most efficient outcome. International bank structures may also yield benefits for the host country economies. De Haas and van Lelyveld (2010), for example, show that the ability of international banks to attract liquidity and raise capital allows them to operate an internal capital market within their bank. This internal capital market provides their subsidiaries with better access to capital and liquidity than what they would have been able to achieve on a stand-alone basis. This may in turn help to reduce the pressure to scale back lending during economic downturns in the host country – a stabilising property for the host country.

During the crisis, national ring fencing activities happened across the euro area (and beyond). One example is the case of Germany, where its regulator BaFin banned Italy’s UniCredit from transferring excess capital in the form of dividends from its German subsidiary back to Milan headquarters. BaFin feared that the transfer could leave German depositors exposed to supporting UniCredit[3]http://www.reuters.com/article/ecb-banks-tests-idUSL6N0S23TB20141012. Arguably, with the establishment of the Banking Union, ring fencing – as a crisis response – should occur less, as the ECB is the supervisor of both the parents (including the branches) and the subsidiaries in the participating member states, and the Single Resolution Board (SRB) the resolution authority. The ECB and SRB have a Banking Union wide mandate and thus take into account all activities of a bank within the Banking Union. This decreases the need for ring fencing responses in the case of the resolution of a cross-border banking group.

However, coordination failures can still occur when the parent bank or one of its subsidiaries operate outside the Banking Union.

2.2 National interests

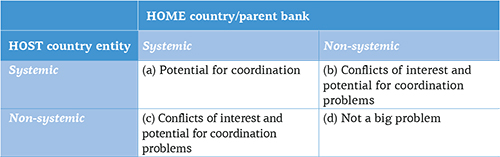

Herring (2007) states that cross-border coordination fails when national interests do not overlap, which might be due to three different asymmetries. First, there could be supervisory asymmetries, as the supervisory authorities may differ in terms of staff skills and financial resources. Second, there might be an asymmetry in accounting, legal and institutional infrastructure. Third, different national resolution regimes may prompt non-coordinated behaviour in the case of cross-border bank resolution. The key issue in overcoming these asymmetries in national interests is whether the banks are systemically important in either or both countries (see Table 1).

Table 1: Alternative patterns of asymmetries

Source: Herring (2007)

Only when a major bank’s activities are systemic in the home and host countries, there is potential for coordination (see case a), which is for example the case for the Vienna initiative. The Vienna Initiative in 2009 was successful in coordinating international actors operating in Central Eastern Europe to avoid massive capital retrenchment at the height of the financial crisis (see Box 1 for a more detailed description). De Haas et al. (2015) show that even though both foreign and domestic banks curtailed credit during the crisis, banks that signed the Vienna initiative were more stable lenders to the region than banks that did not participate. Here, the banking problems in both the home and host countries were systemic and the relevant authorities had thus a joint interest to address the banking problems.

Nevertheless, coordination is not always achieved in case a. Fortis is an example of a bank which was systemically important both in Belgium and in Netherlands. Notwithstanding the alignment of interests, the Belgian and Dutch authorities decided to split the bank along national lines, before resolving it, leading to fiscal costs which went far beyond the minimum necessary as deemed by EU State aid rules (see Schoenmaker (2013) for a full description of the Fortis rescue).

In the intermediate cases (case b and c in Table 1), the potential coordination failure is linked to the extent of inward or outward banking. Inward banking is defined as banking claims from abroad towards the country in question, while outward banking captures the exposure of multinational banking groups to other countries, beyond the domestic market.

Focusing on the` outs’, from a host country perspective, a high level of inward banking indicates a high share of systemically important banks in the host country, which might or might not be systemic for the home country (case a and b). This limits the capacity of the host authority to manage the stability of its financial system, including the lending capacity to its economy. From a home country perspective, a high level of outward banking indicates the presence of major international banking groups which are systemic for the home country, and might be systemic or non-systemic for the host countries (case a and c). This poses challenges for the home authority to manage the stability of its international banks and thereby its financial system, especially in the case of cross-border resolution.

The next section will provide an empirical analysis of the extent of inward and outward banking in the ‘outs’.

| Box 1 The Vienna Initiative |

| Causes

When the global financial crisis swept the world in 2008, many countries in emerging Europe proved vulnerable because of their high levels of private debt to local subsidiaries of foreign banks. The debt to foreign and domestic banks was often denominated in foreign currencies. Policymakers in the region became increasingly concerned that foreign-owned banks, despite their declared long-term interest in the region, would seek to cut their losses and run. The banks themselves were also getting worried. Uncertainty about what competitors were going to do exacerbated the pressure on individual banks to scale back lending to the region or even withdraw, setting up a classic collective action problem. Under these circumstances, bank behavior was clearly key to macroeconomic stability. Systemic importance A number of western European banks had major subsidiaries that were of systemic importance in central and eastern Europe. Most of the western European banks were also of systemic importance in their home countries. Cooperation In the face of these risks, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the IMF, the European Commission, and other international financial institutions initiated a process aimed at addressing the collective action problem, starting in Vienna in January 2009. In a series of meetings, the international financial institutions and policymakers from home and host countries met with some systemically important EU-based parent banks with subsidiary banks in central and eastern Europe. The meetings were held with 15 systemically important European banks with major subsidiaries in central and eastern Europe and their home and host country supervisors, fiscal authorities, and central banks from Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, and Sweden, as well as Bosnia Herzegovina, Hungary, Latvia, Serbia, and Romania. The European Bank Coordination Initiative has played a major role in averting a systemic crisis in the region (EBRD, 2012). This initiative, which combined appropriate host government policies, massive international support, and parent bank engagement, has helped stabilize the economies in the region. Furthermore, in order to underpin the Vienna initiative’s efforts, the region received 42.7 bn EUR through the first and second joint International Financial Institutions Action Plan. The objective was to support banking sector stability and lending to the real economy. Impact The coordinated response has fostered stability of the European banking system, both in western Europe (where the parent banks are located) and in central and eastern Europe (where major subsidiaries are located). The setting offered a typical coordination problem with high stakes. By setting all parties together, including relevant western and eastern European governments and banks as well as several multilateral financial institutions, a win-win situation could be created. The financial support of the multilateral financial institutions worked as an effective lubricant to get the deal done. However, bank deleveraging during the crisis still hit the region, as documented in the quarterly CESEE deleveraging and credit monitors.[4]Accessible under: http://vienna-initiative.com/type/quarterly-deleveraging-monitors/ Only recently the reports point to a relaxation, stating that cross-border deleveraging at the group level is slowing down, but banks are more selective in their country strategies. |

| Source: Schoenmaker (2013) |

3. The European Banking landscape

This empirical section starts with an overview of cross-border trends in the European banking system. The Single Market allows banks to establish branches in other European Union countries, based on home country control. Host countries have only some limited powers related to liquidity supervision over cross-border branches. Figure 2 shows the percentage of total banking system assets coming from branches or subsidiaries of banks headquartered in other European Union or third countries. This allows us to capture the extent of cross-border banking penetration in European banking.

Cross-border banking within the European Union had been rapidly increasing to 20 per cent in the run up to the global financial crisis. Figure 2 illustrates the rise of cross-border penetration from EU countries and subsequent decline since 2007, continuing its trend with the start of the European sovereign debt crisis in 2010-2011. The geographical breakdown of cross-border banking activity reflects a retrenchment on the back of the global financial crisis. Moreover, banks that received state aid were often pressured by national authorities to maintain domestic lending, cutting down on foreign lending. More recent data for 2014 suggest that cross-border deleveraging process is bottoming out. Cross-border penetration from third countries was more stable at about 8 per cent throughout the period, but also showed a temporary decline after 2007.

Figure 2: Cross-border penetration in European banking

Source: Bruegel based on ECB data. Note: Share of assets held by banks headquartered in other EU countries and third countries over total banking assets in the European Union. The share is calculated for the aggregated EU-28 banking system.

The remainder of this section provides first data on the Banking Union Area, which started in November 2014. Next, outward banking from the ‘outs’ is illustrated: the cross-border branches and subsidiaries in the Banking Union Area from banks headquartered in the ‘outs’. Finally, inward banking to the ‘outs’ is analysed: the cross-border branches and subsidiaries in the ‘outs’ from banks headquartered in the Banking Union Area.

3.1 The Banking Union Area

As discussed before, the deeper rationale for the Banking Union is cross-border banking in the Single Market. We expect therefore for a genuine Banking Union market to develop, where cross-border banking groups can transfer excess capital and liquidity across the group, and supervision is done at the consolidated level.

The international orientation of a country’s banking sector can be captured by the outward banking claims of the largest banks. Splitting the assets of these banks into the home country, other EU countries and third countries allows gauging the potential for coordination failure between national authorities in crisis management.

The basic source for the geographical split of assets is banks’ annual reports. When information on the geographical segmentation of assets is not available, we use the segmentation of credit exposures of the loan book, the most important asset class, as a proxy. Further information on credit exposure is available in the published stress test results for 2014 of the European Banking Authority. The full methodology for measuring geographic segmentation is described in Schoenmaker (2013). Under the new Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV), financial institutions must disclose, by country in which it operates through a subsidiary or a branch, information about turnover, number of employees and profit before tax. This extra information allows us to refine the geographical split at country level.

Table 2 shows the top 25 banks in the Banking Union by end-2014. In terms of assets, 74% of assets are held within the Banking Union Area (the columns home and Banking Union combined), 17% in the rest of the world, and only 9% of assets are held in other EU countries. While 59% of assets were held with the respective home countries before entry to the Banking Union, this ‘home’ percentage increased to 74% when the home base expanded to the Banking Union Area. Only a few Banking Union Area banks have substantial activities in other EU countries. Examples are UniCredit with 23%, KBC Group with 24% and Erste Group with 37% (all three mainly in Central Eastern Europe) and Banco Santander with 32% (mainly in the United Kingdom).

Table 2 Top 25 banks in Banking Union, end-2014

Source: Bruegel based on annual reports. Notes: Top 25 banks are selected on the basis of total assets (as published in The Banker). The market share in the Banking Union is defined as the share of total assets in the Banking Union of the respective banking group over total banking assets in the Banking Union. The geographical breakdown refers to the share of assets in the home market, the Banking Union, the rest of Europe and the rest of the world over the total assets of the respective banking group. The home and Banking Union shares add up to the total Banking Union share. The last line of the top25 banks is calculated as a weighted average (weighted according to assets).

3.2 Outward banking

Moving from the Banking Union Area to the ‘outs’, Table 3 indicates the geographic segmentation of the top 10 banks outside the Banking Union. Overall, these banks hold 50% of assets in their home country, 10% in the Banking Union market, 8% in other EU countries and 32% in the rest of the world. On a bank level, Barclays (UK) holds 22% of assets in the Banking Union, mainly in Italy (5.1%), Spain (3.7%), Germany (3.4%) and France (2.9%)[5]It should be noted that Barclays is divesting its retail banking activities in Italy, Spain and Portugal and is thus reducing its presence in the Banking Union Area (FT, 2015).. Nordea (Sweden), SEB Group (Sweden) and Danske Bank (Denmark) have assets amounting to 18%, 14% and 12% in the Banking Union (particularly in Finland and in the Baltics)[6]In this context, Estonia sees, for example, the two Swedish subsidiaries as systemically important (accessible under … Continue reading, respectively. These last three banks are pan-Nordic banks.

This indicates that the ‘outs’ are characterised by a large share of outward banking claims to the rest of Europe, especially the Scandinavian countries. If all of the ‘outs’ were to join Banking Union, the potential improvement would be the 10% of assets held in the Banking Union and the 8% of assets held in other EU countries that are not yet part of the Banking Union.

Table 3 Top 10 banks outside Banking Union, end-2014

Note: see Table 2. The top 10 is ranked by total assets.

In countries characterised by an extensive part of outward banking, the resolution of these multinational banks poses an important challenge. The famous quote ‘banks are international in life, but national in death’ by Mervyn King captures best what is at stake (quoted in Turner, 2009, p.36). In the case of multinational banks, if supervision and resolution are national, home-country authorities only take the domestic share of a bank’s business into account when considering a bank rescue, without paying much attention to the cross-border externalities of their actions (Schoenmaker, 2011; Zettelmeyer, Berglöf and De Haas, 2012). In this context, the eventual burden sharing will be contentious between the home and the host country, inducing outcomes that are both inefficient and detrimental for systemic stability (Goodhart and Schoenmaker, 2009). The abortive rescue of Fortis, which put national interests first, is a good example of this coordination failure (Schoenmaker, 2013). While the SRM is a complicated coordination mechanism involving the national finance ministers in addition to the Single Resolution Board, the SRM Regulation mandates a Banking Union wide perspective for the resolution of Banking Union banks (Schoenmaker, 2015). This Banking Union wide mandate should prevent the splitting of banks along national lines in the resolution process[7]Note that Article 6(1) of the SRM Regulation forbids discrimination against entities on national grounds..

3.3 Inward banking

Moving from outward to inward banking, Table 4 reports the foreign-owned assets in EU countries as a percentage of total assets of that country’s banking sector, domestic and foreign-owned. It emerges that non-Banking Union countries are characterised by high inward claims from other European Union countries, as the extent of inward claims coming from the European Union is actually higher in the ‘outs’ (19%) compared to the ‘ins’ (14%).

In the non-Banking Union countries, the cross-border share in total assets of a country’s banking sector is particularly high in Central Eastern Europe, which exhibits shares between 45% and 90%. By contrast, Sweden and Denmark report only moderate inward claims of around 10% and 18%, respectively. The United Kingdom is a special case. It is the only EU country which experiences more claims coming from banks in the rest of the world (32%) than from banks headquartered in the rest of the European Union (17%). Major US and Swiss (investment) banks form a substantial part of the share coming from the rest of the world. These banks use their London office as a spring plank to conduct business across the European Union. This reflects the importance of London as an international financial centre.

Table 4: Cross-border share in % of total assets of a country’s banking sector, end-2014

Source: Bruegel based on ECB Structural Financial Indicators. Note: Share of business from domestic banks, share of business of banks from other EU countries, and share of business of banks from third countries are measured as a percentage of the total banking assets in a country. Banking Union, Non-Banking Union and EU are calculated as a weighted average (weighted according to total assets).

Zooming in on the ‘outs’ in Central Eastern Europe, table 5 reports a further breakdown of their banking assets from banks coming from other countries according to where their headquarters are based: in the Banking Union, the non-Banking Union Area or the rest of the world. On aggregate, the banking sector in the Central Eastern European countries is characterised by 70% cross-border claims, where 65% operate as subsidiaries and only 5% as branches. The subsidiaries can be broken down further into whether their parents are located in the Banking Union Area or outside. An overwhelming 93% of the subsidiaries have their parent bank located in the Banking Union Area, compared to 1% coming from the non-Banking Union Area and 6% from the rest of the world.

A look at the country-level confirms the importance of claims coming from the Banking Union Area: with 99% and 97% respectively, the Czech Republic and Croatia report by far the most extensive share of foreign owned subsidiaries coming from the Banking Union Area, followed by positions of Romania, Hungary and Poland of around 90% to 95%. Bulgaria exhibits slightly lower claims, with 82% coming from the Banking Union Area. On aggregate, all ‘outs’ in Central Eastern Europe, except Hungary, have more than half of their banking assets coming from subsidiaries of banks headquartered in the Banking Union Area. For Hungary, this number is 37% (95% of the 39% via subsidiaries).

Table 5: BU and non-BU share in % of total assets in the CEE’s banking sector, end-2014

Source: Bruegel based on ECB and SNL financials (data on (BU) Banking-Union, (non-BU) non-Banking Union and (RoW) Rest of World). Note: * the data for Croatia is taken entirely from SNL. Non-Banking Union is calculated as a weighted average (weighted according to total assets) for CEE. The sum of SNL calculated data does not add up completely to the data provided by the ECB due to different methods of collection.

During the financial crisis, supervisors tightened restriction on intra-group cross-border transfers, limiting the ability of multinational banking groups to re-allocate capital and liquid assets from subsidiaries with an excess to those in need of capital and/or liquidity. Hence, there is a tendency for higher capital and liquidity for subsidiaries on a stand-alone basis, which translates into a higher cost of capital for the host country (IMF, 2015).

Moreover, even though the Vienna Initiative was successful in coordinating policy during the recent financial crisis, Banking Union membership could substitute for such ad-hoc arrangements. First, this would allow consolidated supervision, as opposed to sub-entity stand-alone supervision. Darvas and Wolff (2013) note that in the central and eastern European countries, national authorities had a hard time addressing credit booms through national supervisory action, since banks used supervisory arbitrage. By the same token, national authorities had difficulties in preventing a massive withdrawal by Western European banks; the Vienna Initiative was in the end decisive to maintain the lending capacity in Central Eastern Europe. In the case of Banking Union membership, these issues could be more easily addressed. Second, it would give more regulatory certainty in times of crisis, as it can be seen as a permanent ‘lock-in’ coordination tool for all the participating countries, avoiding ad-hoc measures.

Summing up, we can ask what the numbers are telling us. As we have shown, the Nordics are characterised by extensive outward banking towards the Banking Union Area, while inward banking from the Banking Union is particularly important for Central Eastern Europe. Taken together, this indicates that these ‘outs’ might benefit from Banking Union membership. That leaves the United Kingdom, which as an international financial centre has more outward banking towards the rest of the world than to the Banking Union. For the United Kingdom, the option of Banking Union membership thus seems to be partly relevant. But Banking Union is also important for London’s position as gateway to Europe for international banks.

4.4 The political dimension

When confronted with cross-border banking, the financial trilemma states that policymakers face a choice between supranational policies and national restrictions. The supranational option is supervision and resolution within the Banking Union. The alternative of national restrictions includes the emerging practice of requiring the subsidiary form cross-border banking business, as witnessed in Central Eastern Europe. Through the separate licence for these subsidiaries and subsequent supervision, the host country can control these subsidiaries. But such stand-alone subsidiaries experience a higher cost of funding, as discussed earlier.

While the empirical findings in the previous section suggest that the Banking Union might be beneficial for the ‘outs’, this is not reflected in the political discussions in the ‘outs’ about joining Banking Union. Figure 3 indicates that opposite opinions emerge. In the Nordics, Sweden declared in 2014 that it will not join Banking Union in foreseeable time, and has not since changed substantially idea on this matter[8]http://www.government.se/sweden-in-the-eu/eu-policy-areas/economic-and-financial-affairs/, remaining the United Kingdom’s most sceptical ally. By contrast, the Danish government declared in April 2015 that it wants the Scandinavian state to become a part of the Banking Union, as it views it as being in the interest of its financial sector (Østergaard and Larsen, 2015). However, a referendum on 3 December 2015 rejected closer ties with the European Union on a range of issues, and might be an indicator of a less positive stance with respect to the Banking Union membership[9]http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-12-02/eu-skepticism-rife-in-denmark-as-referendum-polls-signal-nej-. In central and eastern Europe, the Czech Republic remains sceptical of an eventual participation in the Banking Union, and Hungary and Poland adopted also a “wait” and “see” approach. For Hungary, the findings from the National Bank by Kisgergely and Szombati (2014) summarise the topic well. Bulgaria and Romania are more positive about joining the Banking Union. In July 2014, Bulgaria announced that it would seek to join the Banking Union, by mid-2016, as poor supervision led to the collapse of its fourth biggest lender[10]http://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-cenbank-idUSKCN0RO22B20150924#3HLqIKc7c1qM4KjW.97. Romania too has embraced the idea of joining the Banking Union from early on (Isărescu, 2013).

Figure 3: Member State’s standpoint on the Banking Union

Source: Press releases and National Central Banks, as of Dec. 2015.

These “wait” and “see” positions are often motivated by the following considerations. First, joining the Banking Union might imply joining the Economic and Monetary Union beforehand. However, as highlighted in section 1, the rationale for the Banking Union is two-fold. At the height of the European debt crisis in 2012, Banking Union emerged as a remedy against the sovereign-banking loop in the euro area. This loop is linked to the single currency. In the long-term, we have argued that the Banking Union’s ultimate rationale is more linked to cross-border banking in the Single Market, which goes beyond the single currency. Following the latter argument, the debate surrounding the question of opting-in is not necessarily a debate about joining the full package, e.g. joining both the Economic and Monetary Union and the Banking Union.

The ‘outs’, in particular those in the Nordics and Central and Eastern Europe, could join the SSM and the SRM on a bilateral basis, which is advantageous given their large share of outward and inward banking as observed in section 3. The SSM and SRM Regulations explicitly allow for this opting-in. The ‘outs’, except for Sweden and the United Kingdom, have already signed up to the intergovernmental agreement on the Single Resolution Fund. The benefit of opting in is enhanced coordination of supervision and resolution. Moreover, it would give the ‘outs’ a seat at the table at the Supervisory Board of the ECB and at the Single Resolution Board, as well as some safeguards for non-euro area opt-ins, such as the reasoned disagreement procedure and the exit clause[11]The exit clause means that non euro-area European Union members, unlike the euro-area members, are actually allowed to terminate their participation in the Banking Union.. However, an opting-in country has more limited influence in the decision-making process within the SSM compared to a euro area country, as the former has no seat in the Governing Council of the ECB. The Governing Council is the highest decision-making body within the SSM. Also, liquidity provision by the ECB is not automatic (IMF, 2015).

Second, there are still misalignments between supervision and burden sharing. Nevertheless, joining the ESM for indirect and direct bank recapitalisation should also be made feasible on a bilateral basis. During the Irish banking rescue in 2010, the Western European ‘outs’, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Sweden, joined the rescue package by providing bilateral loans, following the ECB capital key, as some British banks were exposed to Ireland and would thus also benefit from enhanced financial stability in Ireland (Gros and Schoenmaker, 2014). This is a good example that burden sharing among the euro area countries can be expanded if and when needed.

Third, the wait and see approach is an answer to the short track record of Banking Union so far. The SSM has one year of operation, while the Single Resolution Board has started its mandate in January 2016, and has not yet handled a resolution case.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we have argued that the deeper rationale for the Banking Union is related to cross-border banking in the Single Market. The large and substantial outward banking claims to the Banking Union Area, which characterise some of the major banks in the Nordics, and the large inward banking claims from the Banking Union to Central Eastern Europe indicate that these countries could profit from joining the Banking Union. These countries have strong banking linkages with the Banking Union Area.

Joining the Banking Union would imply less cross-border coordination failures, especially when it comes to resolution, and a lock-in tool, to increase regulatory certainty in times of market turmoil. For the Nordics, a membership in the Banking Union would increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the supervision and resolution of the larger European cross-border banks allowing supervision and resolution on a consolidated level. For Central Eastern Europe, the Banking Union would be a more stable arrangement for managing financial stability and maintaining lending capacity than the ad-hoc Vienna Initiative. Finally, the United Kingdom, as an international financial centre, is a special case with both international and European cross-border banking claims.

From a political perspective, member states’ opinion on joining the Banking Union ranges from an outright “no” towards considering Banking Union membership. Experiences of the ‘ins’ with the Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Single Resolution Mechanism, for better or worse, will shape the willingness of the ‘outs’ to join. As cross-border banking is related to the Single Market and not to the single currency, countries could join the Banking Union without joining the Economic and Monetary Union.

References

Acharya, V. (2009). A Theory of Systemic Risk and Design of Prudential Bank Regulation, Journal of Financial Stability 5, 224-255.

Battistini, N., Pagano, M., and Simonelli, S., (2014). Systemic risk, sovereign yields and bank exposures in the euro, Economic Policy 29, 203–251.

Bertay, A.C., Demirguc-Kunt, A., and Huizinga, H., (2011). Is the Financial Safety Net a Barrier to Cross-Border Banking?, EBC Discussion Paper No. 2011-037, Tilburg: European Banking Center.

Cerutti, E., Ilyina, A., Makarova, Y., and Schmieder, C., (2010). Bankers without Borders? Implications of Ring-Fencing for European Cross-Border Banks, in P. Backé, E. Gnan and P. Hartmann (editors): Contagion and Spillovers: New Insights from the Crisis, SUERF Study 2010/5.

Claessens, S., Herring, R., and Schoenmaker, D., (2010). A Safer World Financial System: Improving the Resolution of Systemic Institutions, 12th Geneva Report on the World Economy, London: CEPR.

Constâncio, V. (2012). Towards a European Banking Union, Lecture delivered at the Duisenberg School of Finance, 7 September, Amsterdam.

D’Hulster, K., and Ötker-Robe, I., (2015). Ring-fencing cross-border banks: An effective supervisory response?, Journal of Banking Regulation 16, pp. 169–187, July.

Darvas, Z., and Wolff, G., (2013). Should Non-Euro Area Countries Join the Single Supervisory Mechanism?, DANUBE: Law and Economics Review 4(2), 141-163.

De Haas, R., and van Lelyveld, I., (2010). Internal Capital Markets and Lending by Multinational Bank Subsidiaries, Journal of Financial Intermediation 19, pp. 1–25.

De Haas, R., Korniyenko, Y., Pivovarsky, A., and Tsankova, T., (2015). Taming the Herd? Foreign Banks, the Vienna Initiative and Crisis Transmission, Journal of Financial Intermediation, 24 (3), 325-355.

EBRD, (2012). Vienna Initiative – moving to a new phase, Factsheet, April.

Eichengreen, B. (1999). Towards A New International Financial Architecture: A Practical Post-Asia Agenda, Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics.

Erce, A., (2015). Bank and Sovereign Risk Feedback Loops, ESM Working Paper Series No. 1, European Stability Mechanism, Luxembourg.

European Systemic Risk Board (2015) ‘ESRB Report on the Regulatory Treatment of Sovereign Exposures’, European Systemic Risk Board, Frankfurt.

Financial Times, (2015), Barclays to lose £200m on Italian retail bank sale, 3 December, London.

Goodhart, C., and Schoenmaker, D., (2009). Fiscal Burden Sharing in Cross-Border Banking Crises, International Journal of Central Banking, 5, 141-165.

Gros, D., and Schoenmaker, D., (2014). European Deposit Insurance and Resolution in the Banking Union, Journal of Common Market Studies, 52, 529-546.

Herring, R., (2007). Conflicts between Home and Host Country Prudential Supervisors’ In D. Evanoff, J. Raymond LaBrosse and G. Kaufman, eds., International Financial Instability: Global Banking and National Regulation. Singapore: World Scientific, 201–220.

IMF, (2015). Opting into the Banking Union before Euro adoption, Chapter in: Staff report on cluster consultations – common policy frameworks and challenges, Country Report No. 15/97, April.

Isărescu, M., (2014). Relations between Euro and Non-Euro Countries within the Banking Union, Speech at the 15th International Advisory Board of UniCredit, Rome.

Kisgergely, K., and Szombati, A., (2014), Banking Union through Hungarian eyes – the MNB’s assessment of a possible close cooperation, MNB Occasional Papers 115.

Obstfeld, M. (2009). Lenders of Last Resort in a Globalized World, CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP7355.

Østergaard, M., (2015). Comments on the report on possible Danish participation in the Banking Union, accessible under https://www.evm.dk/english/news/2015/15-05-11-banking-union

Pauly, L. (2009). The Old and the New Politics of International Financial Stability, Journal of Common Market Studies 47, pp. 955–975.

Rodrik, D. (2000). How Far Will International Economic Integration Go?, Journal of Economic Perspectives 14, pp. 177–186.

Schoenmaker, D., (2011). The Financial Trilemma, Economics Letters 111, 57-59.

Schoenmaker, D., (2013). Governance of international banking: the financial trilemma, Oxford University Press.

Schoenmaker, D., (2015). Firmer Foundations for a Stronger European Banking Union, Bruegel Working Paper, 2015/13.

Turner, A., (2009). The Turner Review: A Regulatory Response to the Global Banking Crisis. London: Financial Services Authority.

Véron, N., (2015). Europe’s radical Banking Union, Bruegel essay series.

Zettelmeyer, J., Berglöf, E., and De Haas, R., (2012). Banking Union: The view from emerging Europe, in Beck, Thorsten (ed) Banking Union for Europe: Risks and Challenges, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The term ‘outs’ refers to the 9 European Union countries outside Banking Union as of January 2015, namely Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sweden and the United Kingdom. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | However, a differentiation emerges, as non-euro countries are not members of the ECB’s Governing Council that is charged with adopting supervisory decisions drafted by the Supervisory Board. |

| ↑3 | http://www.reuters.com/article/ecb-banks-tests-idUSL6N0S23TB20141012 |

| ↑4 | Accessible under: http://vienna-initiative.com/type/quarterly-deleveraging-monitors/ |

| ↑5 | It should be noted that Barclays is divesting its retail banking activities in Italy, Spain and Portugal and is thus reducing its presence in the Banking Union Area (FT, 2015). |

| ↑6 | In this context, Estonia sees, for example, the two Swedish subsidiaries as systemically important (accessible under https://www.esrb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/2015-12-02_ESRB_notification_Eesti_Pank.pdf?9f2dcdc41d0b84b7226e67323033cb56). |

| ↑7 | Note that Article 6(1) of the SRM Regulation forbids discrimination against entities on national grounds. |

| ↑8 | http://www.government.se/sweden-in-the-eu/eu-policy-areas/economic-and-financial-affairs/ |

| ↑9 | http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-12-02/eu-skepticism-rife-in-denmark-as-referendum-polls-signal-nej- |

| ↑10 | http://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-cenbank-idUSKCN0RO22B20150924#3HLqIKc7c1qM4KjW.97 |

| ↑11 | The exit clause means that non euro-area European Union members, unlike the euro-area members, are actually allowed to terminate their participation in the Banking Union. |