In the aftermath of the euro-area sovereign debt crisis, several commentators have questioned the favourable treatment of banks’ sovereign exposures allowed by the current prudential rules. In this paper, we assess the overall desirability of reforming these rules. We conclude that the microeconomic and macroeconomic costs of a reform could be sizeable, while the benefits are uncertain. Furthermore, we highlight considerable implementation issues. Specifically, it is widely agreed that credit ratings of sovereigns issued by rating agencies present important drawbacks, but sound alternatives still need to be found. Should a reform be implemented and a measure of sovereign creditworthiness become necessary, we argue that consideration could be given to the use of quantitative indicators of fiscal sustainability, similar to those provided by international bodies such as the IMF or the European Commission.

1. Introduction

Until the euro-area sovereign debt crisis, sovereign defaults were regarded as a problem of emerging economies. According to Reinhart and Rogoff’s (2011b) dataset, no OECD country defaulted on its domestic debt between 1950 and 2010. Therefore, it is not surprising that sovereign exposures benefit from a special treatment in the current prudential banking regulation, being de facto subject to no concentration limits (i.e. there are no limits on the size of banks’ sovereign exposures as a share of their capital) and to a zero risk weight regime (i.e. there are no explicit capital requirements vis-à-vis credit risk related to exposures to the government).

The sovereign debt crisis has sparked an international debate on the close relationship between sovereign risk and banking crises. It has been argued that since sovereign exposures cannot be considered risk-free, their preferential prudential treatment should be amended accordingly.[1]For example, Nouy (2012), argued that ‘More capital charge against sovereign risk and less incentives for the purchase of sovereign debt should especially be considered in a context where this … Continue reading Some commentators (e.g. Gros, 2013) have pointed out that the problem is particularly acute in the euro area, where governments can no longer order their central banks to inflate away public debt by creating money and purchasing government securities (an option that is instead available to countries that do not belong to monetary unions and retain full monetary sovereignty).

In this paper, looking at the recent literature as well as at real world experience, we provide reasons to be cautious about the balance between the expected benefits of a tighter regulation of banks’ sovereign exposures and the related costs.

First of all, there are several mechanisms that link banks to their domestic sovereigns, and that make their fates strictly intertwined independently of banks’ holdings of sovereign bonds (CGFS, 2011; Angelini et al., 2014).

Second, the fact that banks’ sovereign exposures tend to be large and biased towards the domestic sovereign is not necessarily an inefficiency to be corrected; instead, it could be explained by hedging motives or minimization of transaction costs (Coeudarcier and Rey, 2013).

Third, in a phase of tensions in the sovereign debt market, banks and other domestic intermediaries may have a stabilizing role, counteracting the effects of short-termism and panic selling: their contrarian role in the sovereign bond market may actually contribute to financial stability and reduce the probability of self-fulfilling crises. The Italian and Spanish experiences in recent years are two cases in point.

Fourth, it is too often overlooked that recent regulation has gone a long way towards breaking the perverse banks-sovereign loop that motivates the proposals of prudential regulation reform. The rules on leverage ratios and – in Europe – the supervisory exercises (e.g. the EBA Recommendation on Capital of December 2011 and the 2014 EU-wide stress tests) have already tightened, de facto, the prudential treatment of sovereign exposures. In Europe, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive imposes losses on private creditors before ailing banks can resort to any external financial support, substantially reducing the likelihood of government intervention, and several measures have been taken to strengthen the fiscal framework in order to reduce the likelihood and costs of sovereign crises. Furthermore, the Basel Committee’s oversight body – the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision – while endorsing the new market risk framework stated that the Basel Committee will focus on not significantly increasing overall capital requirements.[2] See the BIS press release, http://www.bis.org/press/p160111.htm.

In the paper, we also provide estimates of the costs of amending the current regulation, both from a microeconomic perspective, by analysing the impact on banks’ balance sheets, and from a macroeconomic one, by considering the effects on sovereign bond markets. We find that the most significant negative unintended effects could stem from the revision of the large exposures regime. The introduction of binding limits on sovereign exposures could force banks to sell sizeable amounts of government bonds. The sheer magnitudes involved could make the exercise a daunting and risky one (see e.g. Constancio, 2015).[3]Furthermore, new regulation could exacerbate the shortage of safe assets owing to the fact that the financial crisis has increased the demand for them and reduced their supply (e.g. Caballero and … Continue reading Should a new regulatory regime significantly impair domestic banks’ ability to act as contrarian investors, there might be a higher risk of self-fulfilling crises, non-linear dynamics, and abrupt re-pricings of sovereign risk with adverse macroeconomic effects.

Concerning implementation, an obvious difficulty, often overlooked in the literature on this subject, is that, should the regulator decide to abandon the zero risk weight regime for sovereign exposures, it would need to find a method to assess sovereign risk. Finding an operational risk measure would be anything but simple because resorting to credit rating agencies is not in our view – for reasons discussed below – a viable option.

Should the need to address this last problem arise, we argue that a central role could be given to the fiscal sustainability measures released by several major international organizations. These measures, which we discuss in more detail below, are not perfect but they do have strong advantages: they capture the fundamental state of a country’s public finances, they are based on sound economic theory, they are well-established and they rely on transparent methodologies.

Finally, in order to avoid pro-cyclical effects, any new regulation should be enforced in ‘normal times’; in a situation in which risks for financial stability are still material, such as the current one in the euro area, one should be wary of taking action that may end up weakening the economy and re-igniting the bank-sovereign loop that we saw in action in 2011-13. The adoption of long phase-in periods may not be sufficient to assuage these concerns, as markets have shown a strong tendency to front-load any regulatory changes.

The paper is structured as follows: first we provide an overview of the special role given to sovereign debt in prudential regulation (Section 2). We then review the reasons put forward in the debate in favour of tighter regulation of sovereign exposures (Section 3), as well as its micro-prudential (Section 4) and macroeconomic impacts (Section 5). Section 6 discusses alternative ways to assess sovereign creditworthiness. Section 7 concludes.

2. The prudential treatment of sovereign exposures for banks

The Basel rules envisage a special treatment for sovereign exposures, in terms of capital requirements as well as liquidity requirements[4]For a more thorough discussion of the regulatory framework of sovereign exposures, we refer the interested reader to Lanotte et al. (2016)..

2.1 Capital regulation

How capital requirements vis-à-vis sovereign exposures are set depends on whether banks classify the exposures in the trading book or in the banking book. The requirements for exposures classified in the banking book are determined by their credit risk, while the requirements for exposures in the trading book are a function of their market risk.

Treatment of sovereign credit risk. – According to the Basel rules, the capital requirements for credit risk can be determined either with a standardized approach or an Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approach developed by the bank itself and authorized by the supervisory authority.

In the standardized approach, the risk weight assigned to a given sovereign exposure depends on the rating assigned to the sovereign by a credit rating agency that is a recognized external credit assessment institution (ECAI) or by an export credit agency (ECA; for instance, COFACE in France, SACE in Italy); if a bank chooses not to use available ratings, or if no rating is available, a 100% risk weight is assigned.

However, there is a specific provision – the so-called carve-out rule – for domestic sovereign exposures: banks are allowed to assign a zero risk weight ‘to exposures to central governments and central banks denominated and funded in the domestic currency of that central government and central bank’.[5] This approach can be extended to the risk weighting of collateral and guarantees.

In the IRB approach, each individual bank computes the capital requirement for the credit risk of sovereign exposures using its own estimates of the probability of default and loss given default. These parameters are fed into a regulatory formula provided by the Basel Committee, which yields the risk weight.

In the European Union, the Basel rules have been implemented through the Capital Requirements Regulation/Directive (CRR/CRD) package. These packages, the provisions of which are applicable to banks and investment firms regardless of size, mirror the special treatment developed at the international level.

However, when it comes to the sovereign, there are two important differences vis-à-vis the Basel rules, concerning the carve-out rule for banks using the standard approach, and the permanent partial use rule for banks adopting the IRB approach.

As to the carve-out rule, the European framework allows banks to assign a zero risk-weight not just to sovereign exposures denominated and funded in the currency of the corresponding member state, but also to the sovereign exposures denominated and funded in the currencies of any other member state. Consequently, the preferential treatment envisaged for domestic sovereign exposures is applicable to all other European member states.

The ‘permanent partial use rule’ (Article 150, CRR) allows banks adopting the IRB approach to apply the standardized approach to their sovereign exposures – subject to prior authorization by the competent authorities – provided that these exposures are assigned a 0% risk-weight under the standardized approach.

Treatment of sovereign market risk. – In the Basel framework, the treatment of market risks too depends on whether a bank uses internal models or a standardized approach to determine capital requirements.

In the standardized approach, financial assets held in the trading book are subject to two separately calculated charges: i) a capital charge for ‘general market risks’, namely interest rate risks, which is calculated at the portfolio level (where long and short positions in different securities or instruments can be offset); and ii) a capital charge for ‘specific risks’, which is calculated separately for each individual security and is designed to protect against an adverse movement in the price of an individual security owing to factors relating to the individual issuer. In measuring the risk, offsetting is restricted to matched positions in the identical issue (including positions in derivatives).

As far as general market risk is concerned, sovereign exposures are not subject to special treatment. Concerning specific risk, the risk-weight factor is identified using two risk-drivers: 1) external rating; and 2) residual maturity.

However, carve-out rules also apply to specific risks. Paragraph 711 of the Basel rules states that ‘when the government paper is denominated in the domestic currency and funded by the bank in the same currency, at national discretion a lower specific risk charge may be applied’. This provision mirrors the carve-out rule for sovereign credit risk. Accordingly, the risk-weight for these exposures is normally zero.

In the IRB approach, banks face no pre-set regulatory ratios and use their own internal models to compute the capital requirement for the market risk of sovereign exposures.

The European framework is aligned to the Basel framework as to the treatment of sovereign exposures. Unlike for credit risk, the permanent partial use approach is not applicable to positions classified in the trading book.

2.2 Large exposures

In 2014 the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) introduced harmonized rules on large exposures in order to reduce concentration risk (limiting the potential losses stemming from the default of a single client or a group of interconnected clients), overcome the existing divergences between the different national jurisdictions and complement the risk-based rules with a backstop.

Currently, banks are required to limit their exposures to a single counterparty at 25% of their ‘eligible capital’.

However, sovereign exposures are exempt from the application of this limit, provided they receive a 0% risk-weight in the standardized approach for credit risk.

2.3 Liquidity requirements

Sovereign bonds are the main source of collateral for banks. Primary examples of their use are monetary policy operations with the central bank and repos with other commercial banks, including those cleared with a central counterparty (CCP). Therefore, the impact of sovereign strains on banks’ conditions has also to be assessed with respect to liquidity and funding risk.

The Basel Committee has introduced two minimum standards to strengthen the liquidity of banks: i) the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), which aims to increase the short-term resilience of a bank’s liquidity profile by ensuring that it has sufficient unencumbered high-quality liquid assets to withstand a 30-day stress scenario in the form of a severe net cash outflow; and ii) the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR), which supplements the LCR and aims to provide a sustainable maturity structure of assets and liabilities.

The special treatment of government bonds arises in connection with the liquidity buffer: under the Basel III rules on the LCR, sovereign bonds with a standardised risk weight of 0% under the Basel framework (i.e. those rated AAA to AA-) will be eligible to classify as Level 1 liquid assets, without limits or haircuts.

In the EU, where the LCR was introduced as a minimum standard in 2015,[6]The LCR will be introduced in October 2015. The minimum requirement will begin at 60%, rising in equal annual steps of 10 percentage points to reach 100% on 1 January 2019. the delegated act of the European Commission on the LCR classifies as Level 1 liquid assets all securities issued or guaranteed by EU governments, without limitations or differentiations based on rating.

Within the monetary policy framework, government bonds are the most accepted and valuable type of collateral. In the Eurosystem collateral framework the credit quality of government bonds is considered sufficient if they have been rated by a recognized ECAI above the minimum threshold of BBB-. Following their acceptance as collateral, government bonds are priced and risk control measures apply (i.e. haircuts) in order to determine the amount of liquidity to give to the counterparty that is collateralizing its financing operation. Due to their high degree of liquidity, sovereigns fall into the best liquidity category and benefit from lower valuation haircuts compared with other marketable assets. In any case, as for all eligible assets, haircuts for government bonds differ according to the financial characteristics of the asset and its residual maturities, as well as on the basis of the credit quality (haircuts for bonds rated below A- are higher). Although ECAI’s ratings are the most common instrument for assessing the creditworthiness of sovereigns, under the ECB’s rules on collateral the Eurosystem retains the right to determine whether an issue, issuer, debtor or guarantor meets its credit standards on the basis of any information it may consider relevant.

Before concluding this section, it should be pointed out that sovereign risk is already considered – although not fully – in prudential regulation. The December 2011 formal Recommendation adopted by the EBA’s Board of Supervisors asked national supervisory authorities to require banks to strengthen their capital positions by building up a capital buffer against sovereign debt exposures to reflect market prices as at the end of September 2011, at the peak of the sovereign crisis. Similarly, the exercise run in 2014 required banks to hold capital against sovereign positions classified in the banking book.

Moreover, realizing the imperfect nature of the available risk weighting methods, the Basel Committee has introduced a non-risk-based minimum leverage ratio (defined as the Tier 1 capital divided by a measure of exposures) to supplement and backstop the risk-based capital requirements. Under the leverage framework, sovereign exposures are considered at their nominal value; no specific derogation is envisaged. This amounts to introducing capital requirements against these positions: if a capital ratio of 8.5% is assumed, a leverage ratio of 3% is approximately equivalent to a 35% risk weight.[7]Since January 2015 banking groups disclose their leverage ratio. The final calibration and any further adjustments to the definition of the ratio will be completed by the Basel Committee by 2017, … Continue reading

3. Can the sovereign-banks loop problem be addressed via prudential regulation?

As we remarked in the introduction, several criticisms have been raised concerning the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures. It has been argued that tighter rules would discourage banks to hold an ‘excessive’ amount of domestic sovereign bonds. In this way, the perverse feedback loop between the sovereign’s health and that of the domestic banking system would be loosened.

In this section we subject to closer scrutiny the reasons in favour of tighter regulation of sovereign exposures.

- The home country bias in banks’ holdings of sovereign bonds is not necessarily undesirable. – It is not clear, from a theoretical standpoint, what the ‘appropriate’ share of domestic sovereign exposure in a banks’ portfolio should be. It is certainly true that, on average, banks tend to hold a disproportionate amount of domestic sovereign debt with respect to its weight in the world market portfolio, but this is just an instance of the more general home bias phenomenon, ‘a perennial feature of international capital markets’ according to Coeurdacier and Rey (2013); indeed, the home bias of domestic investors concerns several asset classes (most notably shares) and is by no means peculiar to sovereign bonds. Economic theory provides several explanations for this phenomenon; in particular, it can be argued the home bias does not necessarily represent an inefficiency to be corrected, but instead can be seen as a ‘second best’ solution to other market failures. For example, investing in domestic securities may be justified by hedging motives, relatively low information acquisition costs, and a reduced degree of asymmetric information (Coeudarcier and Rey, 2013; Lewis, 1999).

The European experience could also be read as providing a “second best” justification of the sovereign home bias. Indeed, in most European countries the exposure decreased significantly from the inception of the euro to the beginning of the financial crisis, and it increased afterwards (Figure 1). Angelini et al. (2014) and Battistini et al. (2014) argue that redenomination risk was among the key drivers of the pick-up in home country bias: fearing a break-up of the euro area, for financial institutions it made sense to begin to hedge their positions by country rather than by currency. The asymmetry of information argument (the difficulty of assessing correctly the actual financial conditions of foreign sovereign borrowers) may also have plaid a role -

There is no evidence that financial firms’ purchases of domestic sovereign bonds during the crisis did cause or aggravate the Eurozone crisis; in some countries, they may have helped to contain it. – Figure 1 suggests that the increase in home bias was a consequence – rather than a cause – of the crisis. Figure 2 shows that the increase in Italian banks’ exposure to the domestic sovereign coincided with a reduction of the share of Italian government bonds held by non-residents. This evidence, consistent with the redenomination risk hypothesis, prompts the following question: what would have happened if Italian banks and insurance companies had not absorbed the excess supply of sovereign paper generated by the market overshooting at the height of the crisis, in turn driven by self-fulfilling beliefs about the instability of the monetary union? A similar question can be asked for other countries that experienced financial stress over the crisis.

While we clearly lack a counterfactual, possibly if financial institutions in the financially weak countries had not purchased large amounts of domestic sovereign paper at a time when markets were clearly strongly under-pricing it, the euro area crisis could have been substantially worsened.

Remarkably, euro area banks’ behaviour can be explained by pure market motives: they may have acted as ‘fundamentalist’ or ‘contrarian’ investors, making a profit and at the same time contributing to bring prices closer to their fundamental values.[8]At that time the ECB was unable to stabilize sovereign debt markets, depriving the countries under attack of a powerful stabilization mechanism. Indeed, it can be argued that the lack of a central … Continue reading

Figure 1 – Banks’ holdings of domestic government bonds (% of total assets)

Source: based on Eurosystem data

According to this interpretation, which is consistent with the timing and pattern of events documented in Figures 1 and 2, the increase in domestic sovereign exposures by banks in financially weak countries was a reaction to the crisis, and instrumental to preserving financial stability in the euro area.

-

The link between sovereigns and their banks cannot be severed only by changing the prudential regulation. – The fate of banks will be most likely intertwined with that of their sovereign even if the link arising from banks’ direct exposures to the domestic sovereign is severed, owing to the existence of multiple other indirect channels of contagion (CGFS, 2011; Angelini et al., 2014).[9]For example, fears concerning the solvency of a sovereign borrower affect banks’ cost of funding by reducing the value of both explicit and implicit public guarantees on bank liabilities. Moreover, … Continue reading Sovereign distress is associated with macroeconomic turmoil, depresses the economy, and ultimately increases the insolvency rate of domestic households and firms (Bocola, 2015). According to Laeven and Valencia (2013), in the three years after a sovereign default, the median output loss with respect to the potential is over 40%. It is clear that an economic disruption of this proportion will inevitably have adverse consequences for the health of the banking system.[10]Using their broad dataset (spanning 70 countries and more than two centuries of data), Reinhart and Rogoff (2011a) show that sovereign crises do not tend to be followed by banking crises. However, … Continue reading Therefore, the solution to the bank-sovereign loop problem is unlikely to be provided by micro-prudential tools.[11]One could argue that macro-prudential instruments would be more useful. For example, one could impose a macro-financial capital buffer, which is independent of the sovereign bond holdings of each … Continue reading

Figure 2 – Italian general government securities holdings by sector (shares of total government securities outstanding; % points)

Source: based on Bank of Italy data obtained from the Italian financial accounts. - The problem must be tackled at its root, by reducing the likelihood (and the costs) of sovereign and bank distress. Correcting fiscal imbalances and ensuring sound inter-temporal fiscal policy is a key precondition to financial stability and therefore the main route to severe the bank-sovereign link. On this front, important steps have been taken in Europe following the crisis. A threefold strategy has been adopted in order to 1) reduce fiscal imbalances;[12]The European fiscal framework has been enhanced in several dimensions: for example, the Stability and Growth Pact has been amended, reinforcing both its preventive and its corrective arm (most … Continue reading 2) change the bank supervisory and regulatory framework by establishing the single supervisory mechanism (SSM) and the single resolution mechanism (SRM); and 3) establish a sovereign crisis management system to safeguard financial stability within the euro area.[13]In particular, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) will provide financial assistance to euro-area Member States experiencing or threatened by financing difficulties. Under certain circumstances a … Continue reading

Furthermore, there have been important steps, in Europe, in order to decrease the probability of bank failure – and protect the sovereign from liabilities in case of bank failure. The CRDIV/CRR is the main piece of legislation aimed at making banks more resilient: it introduces, among other things, strengthened capital and liquidity requirements. Besides the regulatory side, banks in the EU have been subject to heightened supervision, with initiatives such as EU-wide stress tests and the creation of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). A number of measures are aimed at reducing the size of a public intervention in the event of a bank failure. The relevant pieces of legislation are the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), the revision of the Deposit Guarantee Scheme Directive and the Single Resolution Mechanism at the Euro-Area level. The BRRD requires that, in case recovery or resolution is needed, private creditors have to be subjected to losses before the firm can resort to any external financial support. Also, this external financial support does not (or at least not exclusively) come from the public sector. The national resolution funds and national deposit guarantee schemes, privately funded, will play an important role in providing financing in the event of resolution. In the case of the Euro-Area countries, a mutualised, privately funded single resolution fund has been created.

Summing up, the benefits to financial stability that could stem from a tightening of the prudential treatment of sovereign exposures appear overstated. Furthermore, the idea that the bank-sovereign nexus can be severed in this way is questionable.

4. How large is the potential impact of tighter regulation? Micro-prudential effects

The international debate on the revision of prudential regulation on exposures towards central governments is currently under way and concrete proposals on this issue have not yet been put forward. In what follows we focus on possible revisions of the current regulation in two main fields: 1) capital requirements on credit risk; 2) large exposure discipline.

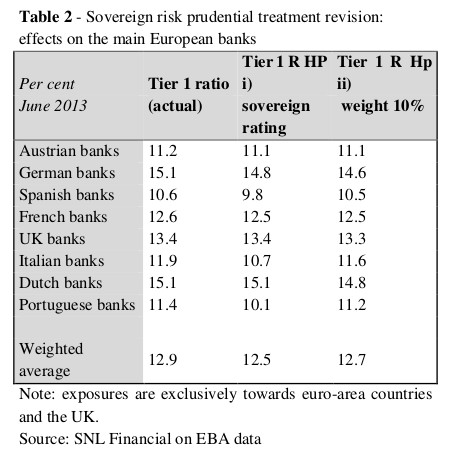

A first look at the data (see Table 1) [14]We consider public data on sovereign exposures, referring to June 2013, for 39 European banking groups, belonging to 8 countries (Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and … Continue reading shows that Italian banks had the highest share of sovereign exposures in total assets (13.1%, more than twice the European average); Portuguese, German and Spanish banks follow, though at a distance (respectively 8.7%, 8.4% and 8%). Furthermore, for the banks in these countries, the share of ‘domestic’ sovereign to total sovereign exposure was especially high, ranging from 77% (Germany) to 93% (Spain), compared with the EU weighted average (72%; see Table 1).

4.1 Tighter capital requirements

As explained above, the European rules on banks’ capital requirements allow banks to set aside no capital against sovereign exposures denominated and funded in the currencies of any member state (sovereign carve-out). To explore possible alternatives we carry out our analysis both on the standardized approach, by assuming different risk weights, and on the IRB methodology.

As regards the standardized approach, two alternative options are explored: (1) removing the sovereign carve-out, forcing banks to apply a risk weight for the calculation of RWA which reflects the actual rating assigned to that country;[15]We considered the ratings assigned by Standard & Poor’s as of June 2013 (the same reference date as the data). (2) Applying a flat 10% weight to banks’ sovereign exposures towards all countries, regardless of rating.[16]This hypothesis has been taken from ESRB (2015).

Table 2 gauges the effect of the two alternative policy options on capital ratios. We start from the Tier 1 ratio as of June 2013 and then assess the effects stemming from the application of risk weights linked to effective ratings (hypothesis i) or a common flat weight of 10% (hypothesis ii).

On an aggregate basis, both options would imply a modest reduction in the weighted average Tier 1 ratio (40 and 20 basis points, respectively).[17]Consistent results have been found by the ESRB (2015) though data refer to end-2011. However, aggregate figures hide significant cross-country heterogeneity. Under the first option, Portuguese, Italian and Spanish banks’ average Tier 1 ratio would be reduced by 130, 120 and 80 basis points, respectively. Other jurisdictions would face smaller effects (for instance, Germany -30 basis points) or no effect at all (Netherlands, United Kingdom, France and Austria). The results for Portugal, Italy and Spain are due to their sovereign’s rating, combined with the ‘home bias’ issue.

The alternative hypothesis (10% flat risk weight) would entail a large decrease in capital ratios for those banks whose sovereign exposure is higher in absolute amount; in particular, German and Italian banks would face a reduction in their average capital ratios of 50 and 30 basis points respectively.[18]Data from the ECB Comprehensive Assessment, updated as of June 2014, show that the average Tier 1 ratio for the 15 main Italian banking groups would be reduced by 160 basis points under the first … Continue reading

As regards internal models approach, we simulated the effects of IRB methodology approach on a subsample of Italian banks and – under different hypotheses of losses given default and maturity – the results are quite similar to those under the standardized approach.

4.2 A tighter large exposures regime

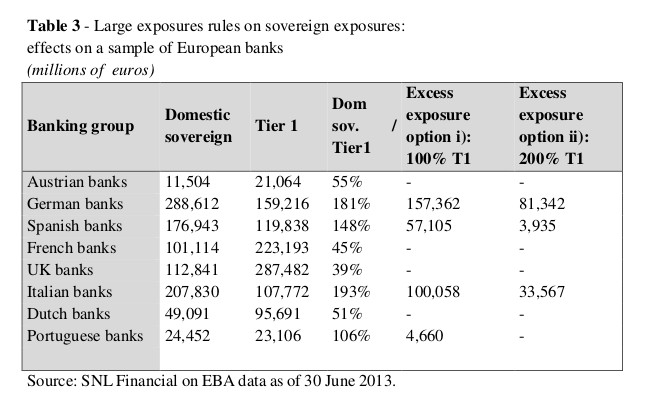

To assess the impact of the large exposures rules on sovereigns we consider the same dataset used in paragraph 4.1, focusing on banks’ domestic sovereign exposure.

We considered the nominal value of sovereign exposures and calculated the excess with respect to 100% (first option) and 200% (second option) of Tier 1.

As shown in Table 3, the application of large exposures limits would have a sizable impact for some countries. Notably, under the most restrictive option, German, Italian and Spanish banks would have to reduce their holdings of sovereign bonds by 157, 100 and 57 billion euros respectively[19]The excess exposures refer to some banks in the national banking system involved. (note that these figures concern only the largest banks).

5. How large is the potential impact of tighter regulation? Macroeconomic effects

5.1 A revision of risk weights

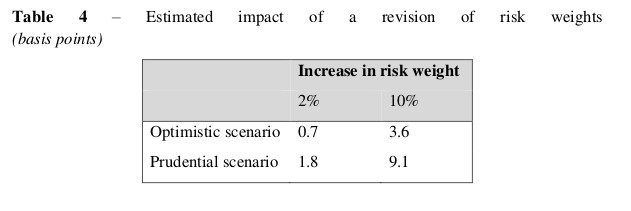

An increase in the prudential risk weights applied to sovereign exposures would also have an impact on the sovereign bond market.

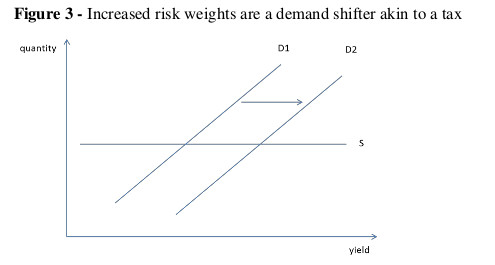

Consider a stylized partial equilibrium model of supply and demand for sovereign bonds. On the demand side, we assume that sovereign bonds behave as a normal good, that is, the higher their yield (ceteris paribus) the higher the quantity demanded (this is not a innocuous assumption: experience gained during the sovereign debt crisis suggests that it may break down under exceptional circumstances). We also postulate that the supply of sovereign bonds is perfectly inelastic. This is plausible over the short run because institutional and political constraints often make it difficult for governments to adjust significantly their budgets and their cash needs within a short period of time. Recent empirical evidence suggests that, in any case, the supply of government bonds has a low interest rate sensitivity (Grande, Masciantonio and Tiseno 2014).

An increase in sovereign risk weights reduces the net yield a bank obtains on a sovereign bond. Such an increase forces the bank to hold more capital, that is, to tilt the composition of its liabilities towards more expensive sources of financing. The added cost of capital can be thought of as a parallel demand shifter: if a bank demanded a certain amount of sovereign bonds for a given gross yield before the rise in sovereign risk weights, it will keep demanding the same quantity of bonds only if their gross yield rises by an amount equal to the added cost of capital. In other words, the increase in risk weights will behave like a tax, as illustrated in Figure 3, where S is the inelastic government supply, D1 is the demand for bonds before the increase and D2 is the demand after the increase. As is well known from the microeconomic theory of taxation, the burden of a tax is higher for the more inelastic side of the market. Under our assumptions, the burden is entirely absorbed by the government.

If one wants to move from a qualitative to a quantitative assessment of a revision of regulatory risk weight one needs an estimate of the elasticity of demand and of the increase in the cost of capital (the additional yield required by banks to compensate for the increase in their cost of financing government bond holdings).[20]Details can be found in Lanotte et al. (2016).

One can estimate a baseline elasticity of demand of around 40%, based on the assumption that demand by non-banks will be unaffected by the reform. However the latter hypothesis could prove excessively optimistic. In particular, the insurance sector could also be affected by prudential reforms and decrease its demand for domestic sovereign bonds, similarly to the banking sector (see below for more details). Furthermore, demand by other sectors could react very slowly to changes in yield. For example, there is ample empirical evidence that portfolio rebalancing by households is quite infrequent (e.g. Guiso et al., 2001). Consequently, the household sector could react to an increase in government bond yields only with a considerable lag. Overall, it is not possible to rule out that the demand by other sectors will be nearly inelastic, at least over the short-to-medium term. To take these risks into account, we consider the opposite scenario in which the demand by other sectors is assumed to be inelastic.

Concerning the additional yield, it is the product of three factors:

where  is the increase in the risk weight applied to sovereign exposures,

is the increase in the risk weight applied to sovereign exposures, is the target capital ratio (which is usually higher than the minimum enforced by regulations),

is the target capital ratio (which is usually higher than the minimum enforced by regulations),  is the cost of equity and

is the cost of equity and  is the return on debt.

is the return on debt.

We assume, in line with the existing evidence,[21]Details can be found in Lanotte et al. (2016). that the target capital ratio is  , the cost of equity faced by the banking sector is

, the cost of equity faced by the banking sector is and that the average cost of debt is around 4.5%. By putting these estimates together we obtain that the banks’ demand shifter is

and that the average cost of debt is around 4.5%. By putting these estimates together we obtain that the banks’ demand shifter is

Given these figures, the estimated impact on Italian government bond yields, is reported in the following table – we present results for two different values of (2% and 10%), but as

is linear in

it will suffice to rescale our figures to compute the effect of revisions with different magnitudes.

Several caveats concerning these estimates are in order.

First, the estimates are derived from a comparative static exercise and therefore represent a comparison between two steady states. Our framework is silent about the transitional dynamics, which might be highly non-linear. Especially for those countries whose banking systems hold a high share of domestic sovereign debt, the key risk is that a change in regulation might feed-back on investors’ beliefs about debt sustainability. In other terms, our comparative statics exercise assumes a partial equilibrium in which the riskiness of government bonds is exogenously given (does not change). This assumption would cease to hold if the reform and the ensuing portfolio adjustments increased the riskiness of government bonds. In this case, the impact of the reform could be much larger than in the prudential scenario. As already mentioned, the burden of the increase in risk weights falls mainly on the government because of its inelastic supply schedule. However, in the transition there would be capital losses for banks, as yields increase (and prices decrease). Banks might also decide to deleverage in order to address at least part of the capital shortfall arising from the revision of sovereign risk weights. Both effects would have significant macroeconomic implications, causing further credit tightening and reducing economic growth.

Second, even after the transition phase, the new equilibrium would probably be less stable than under the current rules, as banks would have less incentives to act as long-term investors, keeping prices in line with fundamentals. The probability of self-fulfilling crises, which is inherent in government bond markets (Calvo, 1988; Ardagna et al., 2007; Giordano et al., 2013; De Grauwe and Yi, 2013) would also increase. Coeteris paribus, exogenous tensions in market conditions would cause larger increases in sovereign bonds. This additional effects are not included in our calculations.

Third, even the relatively cautious assumption that non-banks will not alter their holdings of government bonds (the prudential scenario) could prove over-optimistic. In particular, the insurance sector, which also holds significant amounts of government bonds (especially domestic), [22]Insurance companies held about 260 billion euros of Italian sovereigns bonds as of September 2014. could be affected by the application of new rules (similar to those for banks) under the Solvency II regime. If this is the case, the bulk of the sovereign bonds sold by banks and insurance companies would have to be bought by the household sector, by foreign investors and by other financial intermediaries. This in turn could lead to a crowding out of households’ demand for deposits and other bank liabilities, with negative effects on bank lending to the real economy – an effect that is not captured by the simple framework outlined above.

Fourth, estimates based on past data may be of limited help to forecast the impact of an increase in the supply of government bonds which is quite unprecedented in size.

5.2 A revision of concentration limits

We now turn to the possible impact of the introduction of concentration limits on sovereign exposures. We analyse three hypothetical values for the cap on the ratio between the exposure towards a single sovereign and capital (100%, 150% and 200%).[23]The cap could be introduced on risk-weighted exposures rather than on raw exposures.

To do this we use the same conceptual framework laid out in Section 5.1: conceptually, the fact that the concentration limit is binding means that a kink is introduced in the demand curve (the curve becomes less steep above the kink;[24]Note that the slope is still positive after the kink because it is the sum of a flat demand by banks and an upward sloping demand by non-banks. see Figure 4).

The exposure of Italian banks to Italian sovereign bonds is around 200% of Tier 1 capital (see previous sections). So, for example, with a 100% concentration limit (one of the values in the range we consider), the introduction of the cap would force the banks to shed 50% of their holdings of sovereign bonds.[25]This, of course, is an approximation. An exact calculation should be done on a micro level and then aggregated. However, the 50% figure is also obtained from calculations done on a sample of large … Continue reading This would amount to around 200 billion euros, or 13% of GDP.

Using a methodology similar to the one adopted in Section 5.2, we obtain the estimated impact of the introduction of the cap on government yields under the same two scenarios discussed above. Results are reported in the following table.

As before, these estimates overlook potentially dangerous transitional dynamics and the increased risk – in the new equilibrium – of self-fulfilling changes in the riskiness of government bonds that could make the impact much greater.

Furthermore, there are factors that could bias the estimates, both to the upside and to the downside. On the one hand, our partial equilibrium approach does not allow us to take into account the fact that introducing concentration limits would force banks residing in other countries as well to hold more diversified sovereign exposures and thus the demand for Italian bonds from abroad would probably increase and partially offset the decrease in domestic demand. On the other hand, the estimated elasticity we have used could be too low. For example, Grande, Masciantonio and Tiseno (2014) highlight that under some model specifications the elasticity is estimated to be around 0.03% (instead of 0.02%); such an increase in elasticity would make the impact 50% greater.

6. Implementation issues

Reforming current prudential rules on sovereign risk would require, among other things, the development of a new methodology for quantifying capital requirements.

There would be a number of difficulties in relying on credit ratings to build plausible risk weights for sovereigns (IMF, 2010). First of all, downgrades are not timely: rating agencies prefer not to change ratings frequently and, when the downgrade arrives, it is often sharp (two or more notches). This ‘too-late too-much’ behaviour reduces the information content of ratings and induces pro-cyclicality in prices. Second, using ratings for regulatory purposes creates well-known ‘threshold effects’, especially when a bond exits from the investment grade category. This adds to the pro-cyclicality of rating changes. Indeed, a downgrade may abruptly reduce institutional demand and market liquidity, triggering further sales. Third, ratings do not provide a quantitative risk measure (i.e. a default probability or an estimated monetary loss in case of default), but an ordinal ranking. In the case of sovereign ratings, their accuracy is further undermined by the fact that a sovereign default is a rare event, so that extrapolation from the past is difficult.

It is therefore not surprising that national and supranational authorities currently tend to reduce reliance on ratings in regulation, along the lines suggested by the Financial Stability Board as a follow up to a specific request of the G20 Leaders (FSB, 2010).

Given the substantial limitations affecting credit ratings, it might be preferable to assess sovereign creditworthiness by means of standard fiscal sustainability indicators. As a matter of fact, several indicators have been developed to capture the size of the change in public policies that is needed in order to achieve long-run fiscal sustainability.[26]Conceptually, a country’s public debt is sustainable if it is not larger than the discounted value of the government’s current and future primary surpluses, that is, if the current level of debt … Continue reading Some of them are endorsed by international institutions, such as the S2 indicator regularly computed by the European Commission (European Commission, 2012).[27]Put simply, S2 is equal to the immediate and permanent increase in a government’s structural budget balance that is just sufficient to satisfy its inter-temporal budget constraint. This constraint, … Continue reading

Long-run fiscal sustainability indicators would have a series of advantages if used as a measure of sovereign risk: they are based on a country’s fundamentals and they are not influenced by short-run fluctuations of financial markets or of the economy; they (at least some of them) are firmly grounded in economic analysis;[28]For example, the S2 indicator is based on the inter-temporal budget constraint of the government, which has to hold in equilibrium in most theoretical micro-founded infinite-horizon macroeconomic … Continue reading they rely on very sophisticated and data-intensive demographic and macroeconomic projections; they are computed by independent bodies for several countries using a common methodology. Notice also that fiscal sustainability indicators are not more complex to compute than ratings: indeed, rating agencies use basically the same information and add difficult to assess qualitative judgments.

They also have their own shortcomings. First, they typically (even if not always) focus on a ‘central’ scenario, neglecting the risk that such a baseline scenario might not materialize. Among the more prominent risk factors are the negative shocks to growth or market interest rates, and the risks arising from a fragile and over-exposed financial sector (which could require financial support from the public sector in some circumstances). Even more difficult to quantify (but crucial in the case of sovereign borrowers, as noted above) is the political risk, which partly depends on institutional factors, including the presence, or otherwise, of appropriate budgetary rules and procedures.

Second, they are unable to capture liquidity risk. As remarked by the ECB (2014): ‘governments can encounter the risk of a liquidity crisis even if they are not experiencing any solvency problems’. The events of 2011-13 have shown clearly that short-term fiscal risk may depend crucially on investors’ beliefs. If investors coordinate on an ‘unsustainability equilibrium’, owing among other things to the perceived lack of a backstop by a central bank, the equilibrium may become self-fulfilling. A role may also be played by the maturity, indexation, and currency denomination of the outstanding debt (obviously, long-term domestic-currency-issued debt poses fewer refinancing risks in the short-to-medium run), as well as by the investor base (domestic lenders being probably a more stable source of funding than foreigners). These factors are not considered by standard sustainability indicators.

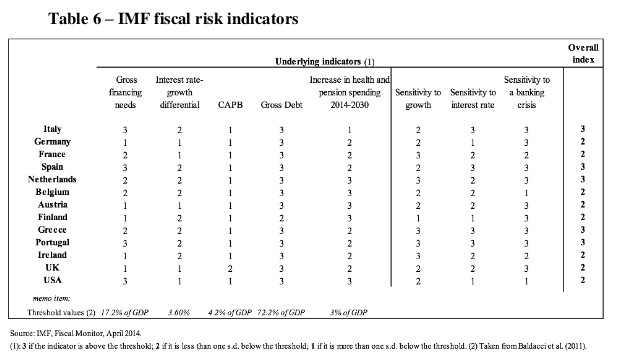

Early warning indicators of fiscal risk recently introduced by the IMF (for details on the methodology, see Baldacci et al., 2011; the latest application is in IMF, 2014) and by the EU commission (see Berti et al., 2012; European Commission, 2012) avoid the main pitfalls of credit ratings and may usefully complement the more established long-run fiscal sustainability indicators. Such indicators are supported by the ECB (2014), according to which ‘early warning indicators for fiscal stress can be important tools for budgetary surveillance in order to allow economic policy time to counteract adverse developments and to help prevent the occurrence of major crises in the first place’ and ‘there is a strong case for the usefulness of such early warning indicators in general,’ even if they have some limitations.

Early warning indicators are based on a wide array of variables. For example, the IMF indicators include variables that are frequently used in analyses of public debt sustainability: the cyclically-adjusted government deficit, the gross public debt, the gross financing needs of the public sector, the interest rate growth differential, and the long-run increase in pension and health spending. Compared with standard long-run sustainability analyses, the inclusion of the government’s gross financing needs can be seen as providing a rough proxy of the short-term refinancing risks. The IMF indicator also includes measures of the impact on the debt-to-GDP ratio of lower than expected growth, an increase in market interest rates, and a bail-out of the banking sector multiplied by the probability of a banking crisis (computed from CDS prices).

For each variable, a threshold value is chosen to maximize the predictive power of the variable as a one-year-ahead leading indicator of a fiscal crisis. This is done by looking at the behaviour of the variable in the period before a crisis. A crisis is in turn identified as a period in which a default/restructuring happens, the country enters an IMF-supported programme, the inflation rate exceeds 35%, or the sovereign spread exceeds 1000 basis points or is more than 2 standard deviations from its historical country mean.

As a final step an aggregate indicator is built, which depends on how many variables are above their ‘stress threshold’ and by how much; variables with greater predictive ability have more weight in the final outcome. Table 6 shows the output of the procedure as taken from the IMF Fiscal Monitor of April 2014. The last column of the table displays the values for the aggregate indicator. The IMF indicator and the related sub-indicators are continuous variables, taking values between 0 and 1, even if the IMF summarizes this information in its publications using three different brackets, with integer values from 1 to 3 denoting low, medium and high risk. Of course, the number of buckets could be increased. A similar indicator for EU countries, called the S0, is regularly published by the European Commission (see Berti et al., 2012).

Indicators in this family are promising because they are more transparent, more oriented towards fundamentals and therefore far less pro-cyclical than credit ratings; if used together with long-run fiscal sustainability indicators, they can provide useful additional information. Moreover, as the indicators generally do not change abruptly, relating risk weights to these factors should be much less destabilizing than linking them to ratings, which sometimes jump by several notches at once.[29]The IMF indicator is not perfect: first of all, the indicator retains some elements of judgment when it comes to the last three indicators: these are based on definitions of ‘negative shocks’ … Continue reading

7. Conclusions

The debate on the reform of the prudential rules on banks’ sovereign exposures is still under way. While current rules are of course neither perfect nor written in stone, the present paper provides a word of caution about the potential benefits and costs of tighter regulation in this area.

Concerning the benefits, one should keep in mind that increasing capital charges on sovereign exposures can hardly be a sufficient safeguard against ‘tail events’ such as sovereign defaults. Indeed, not only regulation does not seem to be a major cause of the observed ‘home bias’ of financial institutions, but also, at a deeper level, the role of the sovereign in a modern economy is so pervasive and crucial that sovereign debt turmoil inevitably translates into severe economic damage. Sovereign debt tensions usually cause widespread defaults in the household and corporate sectors, financial market tensions, and ultimately have a severe impact on the banking sector. Therefore, a change in regulation aiming at insulating a banking system from the default of its domestic sovereign is unlikely to achieve its target.

Furthermore, we highlight that there are already elements of the current prudential framework that take sovereign riskiness into consideration: the leverage ratio regime considers sovereign exposures; the 2011 EBA Recommendation on Capital asked banks to build capital buffers against their sovereign exposures; and stress testing exercises, such as those performed in 2014 in the European Union, explicitly considered stressed scenarios applied to sovereigns and asked banks to strengthen, where necessary, their capital buffers against sovereign exposures.

As to the possible costs, we provide estimates, for a wide sample of major EU banks and under different reform scenarios, of the possible effects of the revision of the current prudential treatment of sovereign exposures. We find that the effects of removing the current zero risk weight may be manageable if weights are moderate, but that imposing tight concentration limits on sovereign exposures could have significant effects.

The reduction in banks’ sovereign exposures could lead to increases in sovereign yields. Our computations suggest that in normal times the effect could be moderate, but the estimates are highly uncertain, as they depend on several factors. First and foremost, we assume that the reaction of investors to the available supply of sovereign bonds is linear, whereas one cannot exclude (as highlighted by several empirical and theoretical contributions) the possibility of non-linearities and multiple equilibria. These could materialize in the presence of market tensions. Historical experience has shown that the demand curve can suddenly invert its slope: during the eurozone debt crisis foreign investors fled certain sovereign debt markets in spite of rising yields. This suggests that impairing domestic financial institutions’ ability to purchase domestic sovereign bonds during a panic-induced crisis, when bond prices tend to move suddenly away from fundamentals, may make the financial system more fragile. Another factor affecting the estimates is the dimension of the base of investors buying the bonds shed by banks. The role of the insurance sector would probably be limited. In many EU countries this sector already holds significant amounts of domestic government bonds and it could be forced also to sell sovereign bonds if new rules similar to those for banks were introduced.

In terms of policy implications, this leads to the conclusion that the net benefits of a reform are elusive and might well be negative. The main way to loosen the close ties between sovereigns and banks as much as possible is to strengthen the soundness of public accounts and, in Europe, to fully develop banking union. If, this notwithstanding, a revision of the current regulatory framework is pursued, it should be based on a comprehensive approach that captures all the relevant aspects, and utmost attention should be paid to its implementation. As is commonly acknowledged, even by advocates of tighter regulation, any new rules should be phased in very gradually, but the tendency of markets to frontload regulatory changes could undo even a long phase-in period.

Should rules on sovereign exposures be revised, it would be necessary to identify methodologies alternative to credit ratings to assess sovereigns’ creditworthiness. Not only are the credit ratings applied to sovereigns subject to the well-known problems common to ratings in general (Financial Stability Board, 2010), but they also suffer from specific limitations. We therefore suggest that a measure of sovereign creditworthiness be based on well-established and analytically sound fiscal sustainability indicators, already published on a regular basis – and with a methodology that it is consistent across countries – by several international institutions (such as the IMF and the European Commission). The literature on public debt sustainability suggests several different quantitative approaches to building metrics of sovereigns’ creditworthiness. Such approaches are worth pursuing from a regulatory policy standpoint as well.

References

Angelini P, Grande, G., and Panetta, F. (2014). The negative feedback loop between banks and sovereigns. Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), n. 213, Banca d’Italia.

Ardagna S., Caselli, F., and Lane, T. (2007). Fiscal Discipline and the Cost of Public Debt Service: Some Estimates for OECD Countries. B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, 7(1), 1-35.

Barclays (2014). Sovereign risk weights for European banks. Cross Asset Research.

Balassone, F., and Franco, D. (2000). Assessing fiscal sustainability: a review of methods with a view to EMU, in Fiscal Sustainability – Essays Presented at the Public Finance Workshop Held in Perugia, 20-22 January 2000, Banca d’Italia.

Balassone, F., Cunha, J., Langenus, G., Manzke, B., Pavot, J., Prammer, D., and Tommasino, P. (2009). Fiscal sustainability and policy implications for the euro area. ECB Working Paper, n. 994.

Baldacci, E., I. Petrova, N. Belhocine, G. Dobrescu, and S. Mazraani (2011). Assessing Fiscal Stress. IMF Working Paper, n. 11/100.

Battistini, N., Pagano, M., and Simonelli, S. (2014). Systemic risk, sovereign yields and bank exposures in the euro crisis. Economic Policy, 29, 203–251.

Berti, K., Salto, M., and Lequien, M. (2012). An early-detection index of fiscal stress for EU countries. European Economy – Economic Papers, n. 475.

Bocola, L. (2015). The Pass-Through of Sovereign Risk. Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Caballero, R.J., and Farhi, E. (2014). The Safety Trap. NBER Working Paper, n. 19927.

Calvo, G.A. (1988). Servicing the Public Debt: The Role of Expectations. American Economic Review, 78(4), 647-61.

CGFS – Committee on the Global Financial System (2011). The impact of sovereign credit risk on bank funding conditions. CGFS Papers, n. 43.

Cottarelli, C. (2014). Fiscal sustainability and fiscal risk: an analytical framework, in Cottarelli, C., Gerson, P., Senhadji, A. (eds), Post-crisis fiscal policy, MIT press, Boston, Mass.

Cottarelli, C., and Escolano, J. (2014). Debt dynamics and debt sustainability, in Cottarelli, C., Gerson, P., Senhadji, A. (eds), Post-crisis fiscal policy, MIT press, Boston, Mass.

Coeurdacier, N., and Rey, H. (2013). Home Bias in Open Economy Financial Macroeconomics. Journal of Economic Literature, 51(1), 63-115.

De Grauwe, P., and Ji, Y. (2013). Self-fulfilling crises in the Eurozone: An empirical test. Journal of International Money and Finance, 34(C), 15-36.

European Commission (2012). Fiscal sustainability report. European Economy, n. 8, Brussels.

European Commission (2013). Vade mecum on the Stability and Growth Pact. European Economy Occasional Papers, n. 151, Brussels.

European Central Bank (2014). Early warning indicators for fiscal stress in European budgetary surveillance. Monthly Bulletin, November.

ESRB – European Systemic Risk Board (2015). Report on the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures.

FSB – Financial Stability Board (2010). Principles for Reducing Reliance on CRA Ratings.

Giordano, R., Pericoli, M., and Tommasino, P. (2013). Pure or Wake-up-Call Contagion? Another Look at the EMU Sovereign Debt Crisis. International Finance, 16(2), 131–16.

Grande, G., Masciantonio, S., and Tiseno, A. (2014). The elasticity of demand for sovereign debt. Evidence from OECD Countries (1995-2011). Temi di Discussione (Working Papers), n. 988, Banca d’Italia.

Gros, D. (2013), Banking Union with a Sovereign Virus: The self-serving regulatory treatment of sovereign debt in the euro area. CEPS Policy Brief, n. 289.

Guiso, L., Haliassos, M., and Jappelli, T. (2001). Household portfolios: An international comparison, in Guiso, L., Haliassos, M. and Jappelli, T. (Eds.), Household Portfolios, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

IMF (2010). Global Financial Stability Report, October.

IMF (2014). Fiscal monitor, April.

Laeven, L., and Valencia, F. (2013). Systemic Banking Crises Database. IMF Economic Review, 61(2), 225-270.

Lanotte, M., Manzelli, G., Rinaldi, A.M., Taboga, M. and Tommasino, P. (2016). Easier said than done? Reforming the prudential treatment of banks’ sovereign exposures. Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), n. 326, Banca d’Italia.

Lewis K. K. (1999). Trying to Explain Home Bias in Equities and Consumption. Journal of Economic Literature, 37(2), 571-608.

Nouy, D. (2012). Is sovereign risk properly addressed by financial regulation?. Banque de France Financial Stability Review, n.16, 95-105.

Reinhart, C. M., Rogoff, K. S., Savastano, M. A. (2003). Debt Intolerance. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 34(1), 1-74.

Reinhart, C.M., and Rogoff, K.S. (2011a). From Financial Crash to Debt Crisis. American Economic Review, 101(5), 1676-1706.

Reinhart, C.M., and Rogoff, K.S.(2011b). The Forgotten History of Domestic Debt. Economic Journal, 121(552), 319-350.

Weidmann, J. (2013). Stop encouraging banks to load up on state debt. Financial Times, 1 October 2013.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | For example, Nouy (2012), argued that ‘More capital charge against sovereign risk and less incentives for the purchase of sovereign debt should especially be considered in a context where this asset class can no longer be considered as a low-risk or risk-free asset class’. Weidmann (2013) observed that ‘a reassessment of the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures of financial institutions is crucial’ in order to break the inter-linkage between sovereigns and banks and to complement European banking union, and that ‘the current regulation’s assumption that government bonds are risk-free has been dismissed by recent experience’. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See the BIS press release, http://www.bis.org/press/p160111.htm. |

| ↑3 | Furthermore, new regulation could exacerbate the shortage of safe assets owing to the fact that the financial crisis has increased the demand for them and reduced their supply (e.g. Caballero and Fahri, 2014). In Europe, this could prolong the current slowdown. Indeed, while in normal conditions one could hope that banks would reinvest the resources obtained by selling government bonds in loans to firms and households, this would be no longer true in a ‘safety trap’ à la Caballero and Fahri (2014): banks would instead simply strive to hoard the fewer safe assets that are left in the market. |

| ↑4 | For a more thorough discussion of the regulatory framework of sovereign exposures, we refer the interested reader to Lanotte et al. (2016). |

| ↑5 | This approach can be extended to the risk weighting of collateral and guarantees. |

| ↑6 | The LCR will be introduced in October 2015. The minimum requirement will begin at 60%, rising in equal annual steps of 10 percentage points to reach 100% on 1 January 2019. |

| ↑7 | Since January 2015 banking groups disclose their leverage ratio. The final calibration and any further adjustments to the definition of the ratio will be completed by the Basel Committee by 2017, with a view to migrating to a Pillar 1 treatment on 1 January 2018. In the EU, the European Commission’s delegated act on the leverage ratio, published on 10 October 2014, identifies all the components needed for its calculation. The monitoring period began on 1 January 2015 and will last 3 years before the final calibration. |

| ↑8 | At that time the ECB was unable to stabilize sovereign debt markets, depriving the countries under attack of a powerful stabilization mechanism. Indeed, it can be argued that the lack of a central bank with such powers in the euro area was among the reasons for the market overreaction (De Grauwe and Yi, 2013). This interpretation is supported by the effectiveness of the mere announcement of the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme in bringing the crisis to an end. |

| ↑9 | For example, fears concerning the solvency of a sovereign borrower affect banks’ cost of funding by reducing the value of both explicit and implicit public guarantees on bank liabilities. Moreover, as sovereign securities are typically used as collateral in repos with central banks and other counterparties, the depreciation of those financial instruments reduces banks’ funding availability. Finally, since the sovereign rating de facto often represents a ceiling on the rating of domestic companies, a sovereign downgrade is generally followed by a lowering of the ratings of other domestic borrowers (Adelino and Ferreira, 2014). |

| ↑10 | Using their broad dataset (spanning 70 countries and more than two centuries of data), Reinhart and Rogoff (2011a) show that sovereign crises do not tend to be followed by banking crises. However, this lack of correlation should be interpreted with caution. For example, in their regressions the authors do not distinguish between externally-held and domestically-held public debt. Most default episodes in their sample concern the former, which is arguably easier for the domestic economy to withstand. The dataset includes only 8 domestic public debt default episodes in western Europe, none of which happened after 1948. |

| ↑11 | One could argue that macro-prudential instruments would be more useful. For example, one could impose a macro-financial capital buffer, which is independent of the sovereign bond holdings of each institution, but is proportional to some measure of the country’s fiscal sustainability. While this approach appears promising, discussing and developing it is clearly outside of the scope of the present paper. |

| ↑12 | The European fiscal framework has been enhanced in several dimensions: for example, the Stability and Growth Pact has been amended, reinforcing both its preventive and its corrective arm (most notably, the ’Six pack’ has given operational content to the debt rule already present in the Maastricht treaty). Furthermore, member countries have strengthened their national budgetary processes and institutions by means of the ‘Fiscal compact’ and the ‘Six Pack’ (see European Commission, 2013). The member countries have also put in place a surveillance mechanism to identify potential macroeconomic and financial risks early on and correct the imbalances that are already in place (the Macroeconomic imbalances procedure, MIP). |

| ↑13 | In particular, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) will provide financial assistance to euro-area Member States experiencing or threatened by financing difficulties. Under certain circumstances a ESM programme may also be backed by ECB operations in secondary sovereign bond markets, with the goal of “safeguarding an appropriate monetary policy transmission and the singleness of the monetary policy” (Outright Monetary Transactions; OMTs). No ex ante quantitative limits are set on the size of Outright Monetary Transactions. |

| ↑14 | We consider public data on sovereign exposures, referring to June 2013, for 39 European banking groups, belonging to 8 countries (Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and United Kingdom). We concentrate on banks’ exposures exclusively towards euro-area countries and the United Kingdom. See Lanotte et al. (2016) for details. |

| ↑15 | We considered the ratings assigned by Standard & Poor’s as of June 2013 (the same reference date as the data). |

| ↑16 | This hypothesis has been taken from ESRB (2015). |

| ↑17 | Consistent results have been found by the ESRB (2015) though data refer to end-2011. |

| ↑18 | Data from the ECB Comprehensive Assessment, updated as of June 2014, show that the average Tier 1 ratio for the 15 main Italian banking groups would be reduced by 160 basis points under the first option and 40 basis points under the second. These effects are broadly in line with those displayed in Table 2. |

| ↑19 | The excess exposures refer to some banks in the national banking system involved. |

| ↑20, ↑21 | Details can be found in Lanotte et al. (2016). |

| ↑22 | Insurance companies held about 260 billion euros of Italian sovereigns bonds as of September 2014. |

| ↑23 | The cap could be introduced on risk-weighted exposures rather than on raw exposures. |

| ↑24 | Note that the slope is still positive after the kink because it is the sum of a flat demand by banks and an upward sloping demand by non-banks. |

| ↑25 | This, of course, is an approximation. An exact calculation should be done on a micro level and then aggregated. However, the 50% figure is also obtained from calculations done on a sample of large banks. |

| ↑26 | Conceptually, a country’s public debt is sustainable if it is not larger than the discounted value of the government’s current and future primary surpluses, that is, if the current level of debt and the current fiscal stance are such that the inter-temporal budget constraint of the government is satisfied. A short introduction to the issue can be found in Balassone and Franco (2000), Balassone et al. (2009), Cottarelli (2014) and Cottarelli and Escolano (2014). Of course, the debt-to-GDP ratio per se is not a reliable sustainability indicator. As documented by Reinhart and Rogoff (2003), among others, several sovereign defaults happened at relatively low debt levels (e.g. below 50% of GDP) and there are cases in which very high debt levels (e.g. Japan today or in England in the 18th century) have been sustained without causing market tensions. |

| ↑27 | Put simply, S2 is equal to the immediate and permanent increase in a government’s structural budget balance that is just sufficient to satisfy its inter-temporal budget constraint. This constraint, in turn, requires that the sum of the outstanding public debt and of the net present value of government primary expenditures be less than or equal to the net present value of government revenues. |

| ↑28 | For example, the S2 indicator is based on the inter-temporal budget constraint of the government, which has to hold in equilibrium in most theoretical micro-founded infinite-horizon macroeconomic models. |

| ↑29 | The IMF indicator is not perfect: first of all, the indicator retains some elements of judgment when it comes to the last three indicators: these are based on definitions of ‘negative shocks’ with respect to the baseline that are somewhat arbitrary. Second, the indicator of the cost of bank bailout is a function of market data and therefore risks being biased and pro-cyclical. Finally, the way in which these shocks are translated into a value between 1 and 3 is model based but not very easy to explain. The first two limitations could be addressed by substituting the three ‘fiscal risk’ sub-indices with others that were included in a previous version of the indicator, namely, the fraction held by foreigners and the average maturity of debt. These variables are objective, publicly available, and clearly related to roll-over risk. |