The final step in the repair of the EU banking sector is cleaning up legacy assets. Otherwise, all of the work we have done to strengthen banks’ capital and assess the quality of their assets will not have the desired positive impact on new lending into the real economy.

Progress is in train but has been slow to date. Although asset quality issues are particularly relevant in some Member States, this is a single market problem and coordinated action is vital for success.

The ongoing effort of supervisors in pushing banks to take action requires that the supporting infrastructure is in place. This means fixing legal systems, which will take time, and addressing market failures in the secondary market for non-performing loans (NPLs), which can be done now. There are legitimate questions about how this should be done, which are addressed in this paper, but those should not be a cause for delay. Whether it be a single European Asset Management Company or a coordinated blueprint for national governments to enact is less important than taking coordinated action urgently.

1. The process of repair – Legacy assets as the last step in the repair of the EU banking sector

European banks have increased their ratios of capital of the highest quality by almost 500bp since December 2011, from an aggregate 9.2% core tier 1 ratio in December 2011 to 14.1% CET1 ratio in September 2016. Common equity has soared since 2011, with increases of €180bn in the period from December 2013 to December 2015. Major EU banks’ capital ratios are now comparable to their US peers. Extensive asset quality reviews (AQRs) have been carried out in most EU countries in order to identify problematic assets and strengthening banks’ provisioning policies.

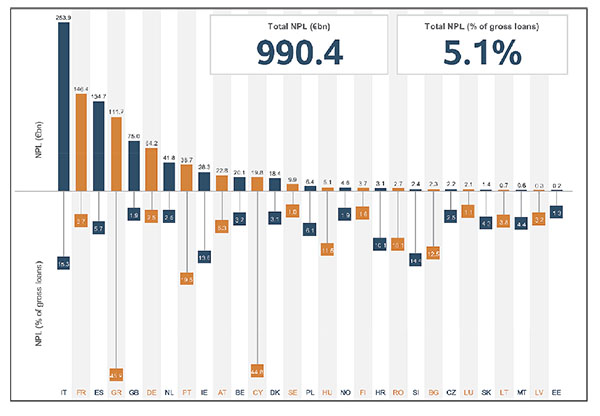

Capital strengthening and the identification of problem assets have been pivotal in restoring confidence in EU banks, but they are not quite enough for the complete repair of the banking sector. The last and, at this stage, crucial step is cleansing balance sheets. This is now imperative because of the scale of the NPL problem across the EU and its impact on economic recovery as capital is trapped in non-performing investments rather than financing the economy. Also, high levels of NPLs are a significant drag on bank profitability and capital generation, raising concerns as to the long term viability of business models. According to the most recent data, the stock of NPLs currently stands at about one trillion euros and the average NPL ratio of 5.1%, with ten Member States reporting average NPL ratios of over 10%.

While there are differences in NPL levels across jurisdictions, three channels of contagion suggest this is a single market problem. The first is the absolute volume of NPLs in the EU, including in its largest economies. The second is the direct and indirect exposure of large EU banks to NPLs across borders. The third relates to banks’ inability to resume new lending in some jurisdictions, which hinders the functioning of the transmission channel of monetary policy and holds back economic growth across the single market.

2. The need for a comprehensive response

In the Report on the dynamics and drivers of non-performing exposures in the EU banking sector, issued by the EBA in 2016, we argued that a comprehensive strategy and a wide range of actions are necessary for tackling the NPLs legacy.

The first area relates to ongoing supervisory pressure on banks to pro-actively tackle NPLs. Banks have to develop a strategy for dealing with NPLs, strengthen their internal procedures, improve their arrears management, and more generally make NPL management active, efficient and informed. Supervisory guidance is needed on collateral valuation, including valuation methodology and possibly minimum requirements for re-valuation as well as on effective arrears management and NPL resolution governance inside banks. The Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) of the ECB has recently made important progress in this area. In general regulatory and supervisory incentives should be in place to promote rapid reduction in NPL levels.

The second area relates to structural issues such as the efficiency of the judicial system, insolvency procedures and out of court restructuring. It is clear that the lengthier the recovery procedures, the wider the ask/bid spread, with an adverse effect on the banks’ incentives to dispose of NPLs. Recent experiences show that reforms in this area can prove a key ingredient for a successful resolution of asset quality problems: the judicial system could be strengthened through improvements in the process, as well as adaptation of regulatory framework; judicial systems could be relieved through a more frequent usage of out-of-court restructuring; accounting and tax regimes can also be reviewed with the objective of positively affect the incentives for banks to deal promptly with NPLs.

The last area relates to the importance of a functioning secondary market in loans to facilitate the disposal of NPLs.

3. Restarting secondary markets in NPLs

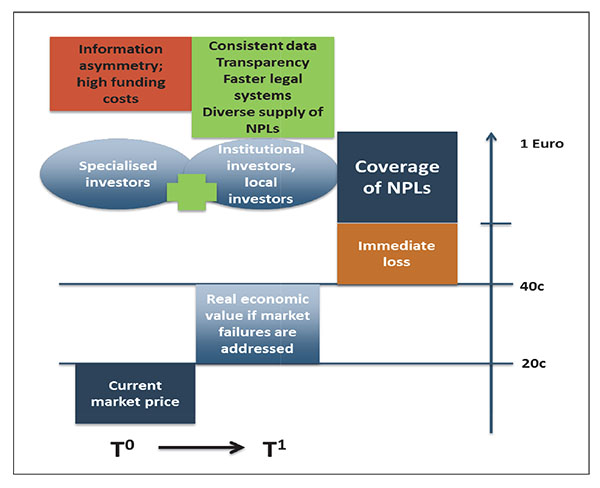

NPL transactions are almost a textbook example of market failure. First, the absence of easily accessible, comparable data on loan, debtor and collateral characteristics generates asymmetric information. Second, an inter-temporal pricing problem occurs since, at present, markets are illiquid and shallow. There is thus a first mover disadvantage to sell into the market.

Forcing banks to write off or dispose non-performing loans in a very short period of time in the absence of a deep and liquid secondary market for impaired assets and with remaining structural impediments may lead to an inefficient gap between bid and ask prices. In such conditions, and in the absence of efficient market clearing prices, forced NPL sales may create financial stability concerns amidst questions about the viability of the sector as a whole. This could also imply a redistribution effect from banks to the few specialized investors operating in the market.

The following corrective actions could address these failures and improve the efficiency of the secondary market:

a) addressing incentives for banks management to take action on NPLs;

b) improving price discovery via

- higher quality, quantity and comparability of data available to investors;

- transparency of existing NPL deals;

- simplification and standardisation of legal contracts;

c) addressing the inter-temporal pricing problem by overcoming current market illiquidity issues. This would entail stepping into the market at a price reflecting the “real economic value” (REV) or future efficient clearing price rather than current market price, with a view to selling into a deeper and more liquid market at a later date.

Purely private sector solutions are not sufficient given the scale of the problem and the market failures prevailing at the moment. Historical examples of success in the disposal of non-performing assets demonstrate the key role of the official sector in kick-starting the market, at least for some segments. In several cases, this has involved governments, or special purpose entities sponsored by public authorities, directly taking over impaired assets or supporting with guarantees their sale to private investors.

4. A possible European scheme

To date, a patchwork of national solutions has been trialed, all different in approach and determining an uneven speed of adjustment. In several success cases, an asset management company (AMC) has proved an effective tool to accelerate the process of repair in bank balance sheets. A common European approach, or a coordinated blueprint for government sponsored AMCs, could provide the following benefits: clarity and simplicity for both banks and investors in understanding the criteria for application of the EU framework for state aid and the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) rules; enhanced credibility of the initiative whilst ensuring that due process is followed in the implementation phase; lower funding costs and higher operational efficiency; critical mass on both the supply and the demand side, pooling assets at the AMC and attracting new investors.

Formal public support could be offered in the shape of a European backed AMC (ideally with “segments” by asset class). Public support could be used to provide capital (say to 8% of total purchasing power), which would in turn crowd in private funding. A hypothetical example would be an AMC purchasing up to a quarter of total outstanding NPLs (about EUR 250 bn) could be capitalised to the tune of EUR 20bn. The solution must be in line with BRRD and State aid rules. Further it should avoid any risk mutualisation of legacy assets.

Banks with NPLs ratios above a given threshold (e.g., 7% NPL ratio) would be required to transfer certain specified assets to the AMC by supervisors. This would require the standardisation of data according to pre-agreed formats (e.g., provided by the EBA).

The process for establishing the AMC would be the following.

Firstly stress tests are used to identify the total envelope of potential state aid for each bank. Such a stress test could take a number of forms ranging from a full balance sheet assessment against complex adverse macro scenarios to more targeted assessments, such as the impact of increasing provisions to meet stressed market price target (e.g. x cents in the euro) levels over a three year timespan. The stress test may also, in isolated cases, identify the need for the immediate resolution of some banks – for instance for banks failing in the baseline scenario.

The State aid envelope calculated in the stress test identifies the theoretical amount of state aid that would be allowed for each bank’s precautionary recapitalisation. This theoretical state aid envelope would determine how much state aid could be used to facilitate the transfer of NPLs. The actual amount of State aid would, in line with existing practice in the application of State aid rules, be equal to the difference between the current market prices and real economic value of the assets actually transferred (i.e., the net present value of future cash flows under the assumption that the asset is held until maturity).

An assessment of real economic value vs current market prices is carried out and banks transfer some agreed segments of their NPLs to the AMC at the real economic value, under due diligence from the AMC and accompanied by full data sets available to potential investors. At the time of the transfer to the AMC, the bank bears losses equal to the possible difference between the book value and the real economic value. The assets are irrevocably transferred at the point of sale.

The transfer of assets to the AMC would hit in the first place the existing shareholders to the extent that the net book value of NPLs is above the transfer price to the AMC. This may be accompanied by a liability management exercise and some bail in of junior debt to equity as determined by European Commission under State aid rules but the extent of this may be considered also in relation to the exercise of future warrants as outlined below.

If within a specified time frame the real economic value remains above the market price, the AMC would be compensated by calling upon a guarantee issued by the government of the Member State where the bank transferring the assets is headquartered. To ensure that banks keep skin in the game and avoid moral hazard issues a mechanism could be introduced to ensure an appropriate compensation of the government.

The mechanism would take the form of a parallel issue of equity warrants to national governments at the time of the asset sale to the AMC, with a penal strike price which would be triggered if the (actual or estimated) sale price at the predefined date remains below the transfer price.

While the AMC could sell the assets at any point in time, there would be a limited timeframe (e.g. three years) for achieving the real economic value and reducing the additional impact of the sale on banks. If that value is not achieved within the timeframe or the assets remain unsold the bank must take the full market price hit, covered if necessary by warrants exercised by the national government as state aid with the full conditionality that accompanies that.

The warrants ensure banks still have skin the game and, as they are issued to national government, also ensure that the AMC capital is fully protected and any eventual cost must be borne by shareholders and if necessary national governments. This element is important also to avoid that a European scheme entails any element of mutualisation of risks, which would not be politically acceptable at this stage. The objective is that the State aid element embodied in the difference between market price and real economic value should reflect only the removal of market imperfections and therefore any price improvement due to increased confidence or economic growth would accrue to the AMC.

5. A critical review of the EBA proposal – incentives, weaknesses and alternative designs

Our original proposal was designed as a sketch, to promote debate and we are aware that many details are missing.

Some criticisms have been well intended but mis-placed. For example, a number of commentators raised the risk of mutualisation of responsibility for legacy assets that would arise by placing NPLs in a common EU AMC. This is not the case. One of the important innovations of the design was precisely to garner all the of benefits that European action offers:- credibility, critical mass; cheaper funding costs – but under no circumstances allowing mutualisation as the AMC was in turn guaranteed by national governments, each remaining responsible for losses generated by banks headquartered in its jurisdiction. Nonetheless, we clearly have a perception problem to deal with.

Other criticisms were more practical. One such was that effort to establish an EU AMC is simply too complex, the scale being unmanageable. We think this depends on the design. We were always clear that the EU AMC may not cover all asset classes not cover all NPLs, but would pick up a critical mass of specific NPLs from relevant portfolios. Moreover, a series of asset class specific AMCs could address the scale problem. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to question how the challenges of operating an EU wide AMC weigh against the benefits of lower funding costs and critical mass that the AMC offers.

Much of the feedback, however, focused on the warrant mechanism. In particular, it has been argued that the potential dilution effect, and associated uncertainty, for equity holders could generate challenges in funding and equity raising.

Our original proposal was designed to identify a system of incentives which was beneficial – or not too detrimental – for any stakeholders, compatible with the current regulatory framework and avoiding moral hazard. A key objective outlined in the original AMC proposal was to achieve a clean break for the bank, with a full sale bringing NPL levels down in a single shot and allowing its management to focus on restoring the sustainability of the business model.

We are not entirely convinced that the proposal would be so detrimental to bank funding, as the warrant would figure alongside other contingent liabilities in the balance sheet of the bank and could be priced fairly accurately if sufficient information on the transfer process is provided to investors. However, other approaches are possible. The simplest way is to ensure a clean sale at conservative prices that may be below the real economic value, but to accompany this with immediate recapitalisation. This entails full burden sharing at the point of sale but eliminates uncertainty. The flip side is that uncertainty is avoided at the expense of crystallising investors’ concerns up front. To compensate for this, a possible upside for the bank could be envisaged, if compatible with State aid rules, in case the final sale price net of servicing costs turns out to be higher than the transfer price. This upfront solution could prove more challenging also for national governments, which might have to step in if the bank is unable to raise the necessary funding in private markets. Alternative options include compulsory insurance purchase by banks, the provision of bonds (or tranches of securitised instruments) to banks in exchange for NPLs, with interest held in escrow accounts until the final sale is completed, and the issuance of contingent convertible instruments (CoCos).

Also, an immediate burden sharing of the junior bond-holders could reduce the incentives for banks and authorities to proceed with the transfer of the assets. If, as we believe, there is a failure in the NPL secondary market, junior bondholders would be affected without any possibility to benefit from the recovery of the prices once the markets become deeper and more liquid. Therefore, some mechanisms – conversion of bonds into equity or write-up clauses – could reduce the redistribution effect and leave some upside also for the bondholders.

There is also the option of doing nothing and leaving the response to purely private solutions. On the latter, however, we note that it does not facilitate the rapid cleansing of the balance sheet of the EU banking sector, which is clearly needed. The inaction so far shows, in our view, that the public sector involvement is necessary. A more attractive alternative is therefore the use of a blueprint for national AMCs, where the scheme would be applied consistently across country but with AMCs established at the national level

6. A common blueprint for national AMCs

The questions over whether a single European AMC would be appropriate vs a blue print for national AMCs appears largely caught up in concerns over mutualisation, or risk sharing, of legacy assets and concerns about unnecessary centralisation of functions at the EU level.

The subsidiarity test, a cornerstone of the European institutional set-up, clearly allocate the burden of proof to those proposing that certain policies are pursued at the Union level. In their 1993 report, Making Sense of Subsidiarity, Begg et al[1]Making Sense of Subsidiarity: How Much Centralization for Europe? Monitoring European Integration By David Begg and et al.November 1, 1993 propose that centralisation is likely to be desirable in the presence of two simultaneous failures of decentralisation:

- First, that non-cooperative policy-making yields results that are significantly worse than cooperative policy-making; and

-

Second, that agreements to cooperate without centralising are not very credible.

They also ask that those proposing centralisation are aware of the risk of diminished accountability. In the case of NPLs it is clear that uncoordinated and sometimes non cooperative policy making is not delivering the necessary progress in addressing the outstanding stock of NPLs, to the detriment of the single market economy. Moreover, existing mechanisms for cooperation, as we have at the EBA, already exist but have not prevented a variety of solutions, and different speed of policy reaction, according to the preferences of national governments and authorities. So some form of centralised policy seem to be necessary.

Our original proposal was designed specifically to avoid any mutualisation by tracing all potential losses to the scheme back to national governments, in the form of a guarantee. On the contrary, potential gains from the scheme would be shared by all contributing governments. Nonetheless, even this high level of protection against mutualisation appears to meet insurmountable political difficulties. Moreover, the dimension of an EU AMC and the diversity of assets it would receive from various Member States, whilst offering considerable advantages of economies of scale and critical mass for stimulating the secondary market for NPLs, would also create technical challenges. For instance, the different legal settings in Member States might impose that the servicing function is outsourced to companies operating at the national level.

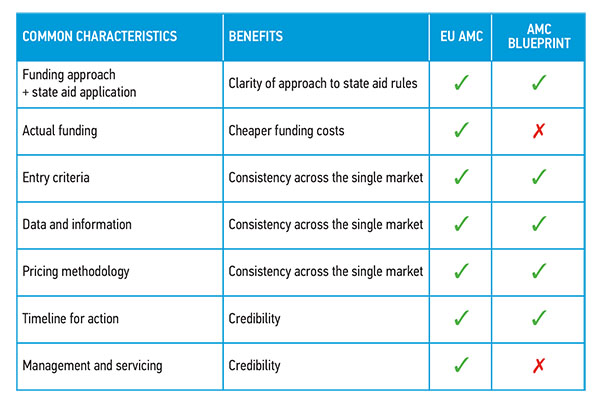

Whilst we remain convinced that a single EU-wide AMC offers the best option for cleaning up NPLs quickly and in the most neutral manner, the most important objectives could be achieved also by developing a common blueprint for AMCs, to be established at the national level, under the management and responsibility of local authorities. The scorecard below compares the benefits of a Single AMC with a blueprint for national AMCs. These approaches should be juxtaposed with the counter factual of doing nothing and sticking with the hodge-podge of differing national approaches that are currently in play, which do not confer the advantages set out here in addressing the NPL problem across the EU banking sector as a whole.

A common EU AMC would provide clarity on State aid rules and consistency of approach. It would in this context enhance credibility, also by removing any uncertainty about political interference in national approaches. A truly common EU AMC would also attract significantly reduced funding costs, which would not materialise with various national approaches.

A common blueprint would however, have two distinct benefits over a common EU AMC. The first relates to perception as it would dispel any misunderstanding about mutualisation of risk for legacy assets across countries. The second is allowing greater flexibility by country depending on the individual circumstances. But this in turn should be set against the trade-off between flexibility on the one hand, and consistency, clarity and credibility on the other.

In short a common EU blueprint for national AMCs offers a reasonable sub set of benefits of a single EU AMC to achieve the objectives of addressing market failures in the secondary market for NPLs, making it a very good second best policy in and hastening the cleansing of balance sheets of the EU banking sector.

7. Conclusions

Our proposal for an AMC aims to address market failures in the secondary market for NPLs. It deals with information asymmetry and the intertemporal pricing problem in a way that, in our view, respects existing rules on state aid and resolution, without mutualisation among EU Member States.

The proposal keeps shareholders on the hook for economic losses but offers viable banks an opportunity to speedily remove problem assets from the balance sheet at an efficient clearing price, albeit with some dilution of shareholders if that price is eventually not realised. The guarantees provided by national government, which is accompanied by warrants to maintain some skin in the game for existing shareholders, avoid any burden sharing across Member States and contains the moral hazard entailed by the State aid. A more efficient secondary markets in NPLs also facilitates supervisory pressure on banks to reduce NPLs and hastens exit from the market of banks that are not viable under efficient market conditions.

An EU solution to NPLs, either as a single AMC or a blueprint for national AMCs, has the added benefits of improving clarity for investors and reducing funding costs. It could create a critical mass in supply and demand of NPLs to further facilitate the market. As a key step in the process of repair for the EU banking sector, it will remove one key impediment to economic recovery across the EU.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Making Sense of Subsidiarity: How Much Centralization for Europe? Monitoring European Integration By David Begg and et al.November 1, 1993 |

|---|