Impaired assets such as non-performing loans (“NPLs”) continue to pose significant problems across the EU. When possible solutions are being considered, “bad banks” or similar impaired asset relief measures are often discussed. However, if they involve support by the State such measures need to be compliant with a set of EU law provisions. This article aims to clarify which interventions are considered to be State aid, and to give an overview of the compatibility conditions that apply to State aid measures. A brief explanation is also given concerning the recent changes brought about by the EU’s new recovery and resolution framework introduced by the Banking Recovery and Resolution Directive (“BRRD”).

1. Introduction

Occurrence of non-performing loans (“NPLs”) is a normal event in the life of a financial institution providing loans, as it cannot be expected that all debtors will always be in a position to repay their loans. Therefore, the management of NPLs should be a standard activity for any credit institution. NPL management without State support should be the normal approach to deal with NPLs in a market economy. Indeed, this is the best way to ensure that banks operate on a level playing field. In addition, if banks have to face the consequence of past lending decisions and cannot shift part of the bill stemming from past lending to the taxpayer, this avoids moral hazard. When such moral hazard is present, credit decisions are distorted and credit is not allocated to the most creditworthy projects; this inefficient allocation of credit hurts the long-term performance of the economy.

The outbreak of the financial crisis, which led to a sudden significant deterioration of financing conditions and evolved into an economic crisis, resulted in a previously unseen proportion of borrowers defaulting on their loans. While some banks and some countries have been less affected by NPLs or were already able to reduce their NPL ratios, the NPL problem still persists in parts of the EU. Indeed, banks with high NPL ratios that are either increasing, stagnating or decreasing much slower than expected, can be found in a number of EU Member States.[1]For detailed statistics on non-performing loans see for example the EBA Risk Dashboard. This publication is available online on: http://www.eba.europa.eu/risk-analysis-and-data/risk-dashboard.

There are multiple ways for banks to deal with NPLs (for example by restructuring loans, enforcing the collateral, or selling NPLs on the secondary market). In normal circumstances, banks deal with their NPLs themselves and will not require interventions by the State. Even in the unfavourable (post-)crisis environment, many banks have been able to significantly reduce their NPL portfolio without public support. For instance, several large Spanish banks[2]For instance, Santander, BBVA, and La Caixa managed their NPLs internally. did not receive public support and dealt with their NPLs by themselves. Likewise, the Italian UniCredit recently raised EUR 13 billion on the market which it will use to hive off a significant portfolio of NPLs.

Nevertheless, since the beginning of the crisis in 2007, as part of a wider strategy and restructuring effort of their banking sectors several EU Member States have deemed public intervention necessary to handle the unprecedented problem of impaired assets. Given market turbulence and uncertainty surrounding the value of such assets, financial interventions by the State were often the only possibility to keep banks afloat and preserve financial stability. In order to safeguard competition and the internal market, EU law however controls the Member States’ interventions. Indeed, as a general rule the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union [3]See: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT. (“TFEU”) prohibits the granting of State aid.

A State intervention has to comply with State aid rules only if it fulfils the following cumulative conditions[4]More guidance on these conditions can be found in the Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) TFEU. This document can be found on DG Competition’s website, … Continue reading:

i. The measure must be granted directly or indirectly through State resources and must be imputable to the State;

ii. The measure has to confer an economic advantage to undertakings;d senior tranche of the secu

iii. This advantage must be selective and distort or threaten to distort competition;

iv. The measure has to affect trade between Member States.

If a public intervention does not fulfil all of the above conditions, it is not qualified as a State aid measure and hence not subject to any compatibility conditions. There have been some public measures to help banks reduce their NPL ratios where the European Commission (“the Commission”) concluded that they did not constitute State aid, for instance because the State charged a market conform price, such that the public measures did not confer an economic advantage to the banks that make use of them. Recent examples of such “aid-free” measures include the Hungarian “bad bank” (MARK)[5]See Commission decision of 10 February 2016 in case SA.38843. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/260961/260961_1733345_231_2.pdf – where NPLs and real estate are bought at market price – and the Italian debt securitisation scheme (GACS)[6]See Commission decision of 10 February 2016 in case SA.43390. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/262816/262816_1744018_70_2.pdf where the State charges a market conform fee to guarantee the investment-grade-rated senior tranche of the securitisation of NPLs.

Alternatively, if a public intervention is granted at terms which are more favourable than what a private investor would grant, it qualifies as State aid and the measure needs to be notified to the Commission who will assess whether it is compatible with the internal market. Member States may only implement the measure after the Commission has given its formal approval.[7]This requirement is laid down in Article 108 (3) of the TFEU. While State aid is in principle prohibited by the TFEU, certain exceptions are foreseen under which Member States may implement public support measures. Given the unprecedented nature and the enormous scale of adverse effects of the crisis, the exception under Article 107(3)(b) of the TFEU that State aid may be given “to remedy a serious disturbance in the economy of a Member State” was invoked to approve State aid to banks at the beginning of the crisis. To increase transparency and lay down detailed compatibility requirements, the Commission established a framework compiling the temporary rules in response to the financial crisis[8]The documents that make up this framework can be found on DG Competition’s website, see: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/legislation/temporary.html which has been regularly revised and adopted to the changing conditions since then. The so-called “Crisis Communications”[9]In particular it concerns: the 2008 Recapitalisation Communication, the 2009 Impaired Assets Communication, the 2009 Restructuring Communication, the 2010 Prolongation Communication, the 2011 … Continue reading which are the core of this framework continue to serve as a basis for the Commission’s assessment of State aid measures for banks.

Since the outbreak of the crisis, EU Member States have implemented and have been implementing various types of aid measures with the Commission’s approval to a very large extent both in terms of number of beneficiaries and aid amounts.[10]The State aid scoreboard which reports aid expenditure made by the Member States, contains a dedicated table on State aid to financial institutions in the years 2008-2015, by type of aid instrument … Continue reading These public interventions have taken the form of recapitalisations, impaired asset relief measures (hereinafter also referred to as impaired asset measures), guarantees on liabilities, and other liquidity measures. Impaired asset relief measures are aimed at “free[ing] the beneficiary bank from (or compensat[ing] for) the need to register either a loss or a reserve for a possible loss on its impaired assets and/or free[ing] regulatory capital for other uses”.[11]Impaired Assets Communication, recital 15. Such measures typically take the form of either a sale whereby the impaired assets are removed from the bank’s balance sheet (see Section ) or of a (partial) State guarantee on the impaired assets that remain on the bank’s books (see Section ).

The nature of banks’ impaired assets has changed since the beginning of the crisis. Initially, it were mainly securities, namely structured credit products (like ABS, CDO, etc.) whose value became uncertain and became illiquid. In a second phase, real estate bubbles burst in certain Member States (Ireland, Spain, etc.), such that real estate loans became non-performing on a massive scale. The last wave of increasing NPLs, which is partly the consequence of the protracted recession in some Member States, affects loans to corporates, SMEs, households etc. The Commission has clarified that Member States may set up impaired asset relief measures only for impaired assets where there is uncertainty concerning their value (which in turn depends on uncertain recovery rates), such that their market price is incorporating an increasing illiquidity premium and risk premium, and therefore the market price drops below what can be considered their real economic value (“REV”)[12]For more detail on the concept of REV, see the explanation in Section ..

When the value of securities drops or when loans become non performing, banks have to adjust the book value (either directly if they are recorded at fair value or indirectly by booking provisions or impairments) of these assets which usually results in significant losses. Banks that want to reduce their exposure to such assets through a sale are sometimes unable to do so because markets have become illiquid and/or because a sale would result in even higher losses than the reduction in value already booked in the accounts. Finally, impaired assets may also be subject to higher risk weights so that they consume more capital at a moment when the bank’s capital position may already be under pressure.

Impaired asset relief measures, often combined with private or State recapitalisations, are a possible tool to remove (or reduce) the risk and uncertainty from a bank’s balance sheet. This approach can also be applied to deal with NPLs in the current context, provided that the relevant EU legal frameworks are respected.

In Section 2 of this contribution we aim to clarify when public interventions are considered to be State aid. In Section 3 we discuss asset transfers to asset management companies while Section 4 covers the situation of asset guarantees. In both sections, we first explain under which conditions the respective measures amount to State aid and then discuss the key compatibility requirements applicable to them. Section 5 then gives an overview of the additional State aid compatibility rules (not covered in the previous sections) that apply to impaired asset measures and explains the rationale behind these requirements and their application in practice. In Section 6 we summarize the recent changes that have been introduced by the Banking Recovery and Resolution Directive[13]Directive 2014/59/EU of 15 May 2014. Available online on: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0059 . (“BRRD”) which became applicable on 1 January 2015. Finally, in Section 7 we draw some conclusions.

2. The definition of State aid in the context of impaired asset measures

As explained in the introduction, not all public interventions constitute State aid. Therefore, it always needs to be established first whether an impaired asset measure actually qualifies as State aid. Since the qualification as State aid is based on a set of cumulative conditions, it is sufficient that one of those conditions is not fulfilled for a measure to be aid-free. In most cases, impaired asset measures are financed directly with public resources and the first condition for a measure to qualify as State aid is met.[14]For simplicity, the condition of imputability to the State will not be discussed in this article. When public interventions are made in favour of selected banks it can be assumed that there is a risk of distortion of competition vis-à-vis banks that do not benefit from such measures. Likewise, given that many banks are active in several Member States, an effect on trade can usually not be ruled out.

However, in some cases it may be less clear whether the remaining condition for State aid, namely that the measure confers an economic advantage on the beneficiary undertaking, is also fulfilled. For this purpose, the so-called market economy operator principle[15]Commission Notice on the notion of State aid, Section 4.2. (commonly referred to as MEO or MEOP) has been developed. The underlying idea is to compare the behaviour of the State or of public bodies to the behaviour of similar private economic operators under normal market conditions. According to the MEO principle, there is no advantage if the State has acted like a normal private party would have done in similar circumstances.

This can be applied to any type of economic transaction in which public actors are involved. For example, in case of a capital injection, the MEO principle translates to whether, in similar circumstances, a private investor of a comparable size operating under normal market conditions could have been prompted to make that given investment on the same terms. Analogically, when assessing loans or guarantees, the relevant question to pose would be whether the State is applying the same conditions as a private creditor or a private guarantor would apply. Finally, when a public body sells an asset, the relevant question to pose is whether a private vendor in a similar situation would have sold the asset at the same or at a better price.[16]Commission Notice on the notion of State aid, recital 74. If the MEO principle is not respected, i.e. if the State acts differently than a private economic operator, then the transaction grants an economic advantage to the recipient undertaking and if all of the other conditions are fulfilled it amounts to State aid.

It is important to note that, this assessment should be made on an ex ante basis, taking into account only the information available at the time when the intervention was decided upon. The rationale behind this is that business decisions under normal market conditions are also solely founded on information that is accessible upfront. Thus, respecting this principle ensures that the comparison is made on realistic terms.[17]Commission Notice on the notion of State aid, recital 78..

3. Existence of aid and cap on transfer price in case of asset transfers to an AMC

One way to address the problems related to troubled assets such as NPLs is to permanently remove them from the bank’s balance sheet. This can be done by transferring the assets to a separate legal entity established for this sole purpose, a so-called asset management company (“AMC”) which is also commonly referred to as “bad bank”. Via this asset transfer, the AMC typically acquires the ownership of NPLs (and in most cases also collaterals of NPLs that have already been repossessed by the bank) and pays a purchase price to the selling bank in return. An AMC can be set up to buy impaired assets from one bank or from several or all banks within a Member State (e.g. NAMA in Ireland, SAREB in Spain). The AMC is often owned, funded or guaranteed by the State in which case it meets the condition of State resources and imputability to the State as explained above. In the rest of this section, we will assume that this condition is fulfilled. As illustrated in Figure 1, the losses that the bank realises by transferring the assets to the AMC amount to the difference between those assets’ net book value (NBV in Figure 1) and the transfer price (TP in Figure 1).

Under the MEO test, no advantage is conferred to the bank selling the assets if the State as a buyer (via the AMC) has acted like a market economy purchaser operating under market conditions would have done in a similar situation. What a private buyer would be willing to currently pay is the current market price (MP in Figure 1) of the asset. To comply with the MEO principle, the transfer price that the State-supported AMC pays to the bank should therefore not exceed the current market price of that asset. In practice, since impaired assets are often non-traded assets for which the price can therefore not be directly observed on stock exchanges or liquid OTC markets, the market price often needs to be estimated for the purposes of carrying out the MEO analysis, as explained in more detail further below.

If the purchase price does not exceed the current market price, the asset transfer does not confer any advantage on the vendor bank and the measure does not constitute State aid within the meaning of the TFEU. On the other hand, if the transfer price exceeds the current market price, i.e. the AMC pays more than what a private investor would currently pay for those assets, an advantage is present. This advantage is equal to the amount by which the transfer price exceeds the current market price, and constitutes the State aid contained in the measure as shown in Figure 1.[18]Impaired Assets Communication, footnote 2 to recital 20 (a), recital 39.

The market price of the assets typically targeted by impaired asset measures may be quite distant from their net book value (NBV in Figure 1). Certain market prices are severely depressed due to lack of transparency and uncertainty regarding the value of the assets (and/or the underlying collateral in case of loans). Therefore, purchasing impaired assets above their market price, thereby granting State aid, may be necessary to allow the bank to remove this source of uncertainty in its balance sheet at a price which is not unduly low compared to the cash flows which can be expected from the those assets.

The previous paragraphs discussed the identification and quantification of State aid. In the following paragraphs, the requirements for any aid identified to be compatible with the internal market will be explained. For an impaired asset purchase by a State-supported AMC, the Impaired Assets Communication has introduced a specific compatibility requirement – on top of the requirements applicable to restructuring or liquidation aid – in the form of a cap on the purchase price which would be paid by the State-supported AMC for the impaired assets. This cap is set at the “real economic value” of the purchased assets. The REV is defined as the “underlying long-term economic value of the assets, on the basis of underlying cash flows and broader time horizons”.[19]Impaired Assets Communication, recital 40. Overall, the Commission considers that the REV is “an acceptable benchmark indicating the compatibility of the aid as the minimum necessary”[20]Impaired Assets Communication, recital 40.. The REV is an estimation of the asset value by disregarding the unexpected distresses caused by the crisis. In contrast to the market price, the REV does not include the additional risk premium which private investors require because of the high uncertainty surrounding the value of the concerned assets and because of their illiquidity. The REV is a prudent estimation of the future cash flows which can be generated by the assets, net of all workout costs, and discounted using an interest rate including a certain risk premium. As market conditions improve over time, the market price should in theory converge towards the REV.

The reason for capping the purchase price of the impaired assets at REV is that an asset transfer should not relieve a bank from losses that are foreseeable. Losses that are expected to occur should be borne by the bank and its shareholders, and not be shifted to the AMC, and hence indirectly to the tax payer. Indeed, impaired asset measures such as asset transfers should only protect banks from unexpected losses (so called “tail risk” in statistics jargon).

Since the purchase price paid by the AMC must not exceed the REV of the transferred assets, the amount of State aid that a Member State can grant under the form of an asset transfer to an AMC it supports is capped at the difference between the REV and the market price of the assets.[21]However as an exception to this general principle, recital 41 of the Impaired Assets Communication notes that Member States may in some circumstances decide that it is necessary to use a transfer … Continue reading

In order to be able to assess a proposed impaired asset measure, the Commission needs to be able to quantify both the market price and the REV. Thus, valuation plays a crucial role in determining whether a given State intervention is compatible with EU law or not. Under normal circumstances, the market price may quite straightforwardly be established in case of a directly observable trading price in a liquid market, in case of pari passu transactions or in case of competitive tender procedures in which private parties also participate.[22]Notion of State Aid Notice, recitals 84, 86-96. Otherwise, benchmarking to directly comparable transactions may serve valuation purposes well.[23]Notion of State Aid Notice, recitals 85, 97-100.

However, for the type of assets subject to an impaired asset measure, there is most of the time no liquid market and no directly comparable transaction taking place at the same moment. In those circumstances, to establish the market price, the Commission may use adjusted benchmarking, namely to adjust the price observed for the sale of assets that have some similarities with the assets covered by the impaired asset measure. The adjustment is based on the difference of the characteristics and quality of the two sets of assets,[24]Notion of State Aid Notice, recitals 85, 101. This approach was for instance applied in case of the Hungarian “bad bank” MARK, which focused on commercial real estate loans.[25]Assets were to be purchased by MARK at a transfer price determined by the formulae that the Commission approved to result in a price that did not exceed the market price, therefore the measure was … Continue reading For the loans collateralised by offices in Budapest, there were some transaction prices observable for such real estate. Conversely, it was more difficult to value loans collateralised by assets located in geographical areas where there were very few transactions. The market price was established via different formulae for the different asset classes to reflect the different characteristics of each of them.

Regarding the REV, it needs to be determined on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the type of the assets and the underlying collateral (and the geographical location of the latter in case of real estate), the expected cash flows, various costs (including servicing costs, funding costs, taxes, maintenance costs), the long-term macroeconomic outlook, and by applying a discount factor that correctly reflects the risks and provides an adequate remuneration for the AMC.[26]Impaired Assets Communication, recitals 40-43 and Annex IV..

Figure 2 Notes

For the National Asset Management Agency (“NAMA”) see Commission decisions of 26 February 2010 in case N725/2009, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/234489/234489_1086237_117_2.pdf;

of 3 August 2010 in case N331/2010, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/237101/237101_1177824_52_2.pdf;

of 29 November 2010 in case N529/2010, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.C_.2011.040.01.0005.01.ENG&toc=OJ:C:2011:040:TOC;

of 29 July 2014 in case SA.38562, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/252347/252347_1584913_91_2.pdf.For SAREB see Commission decisions of 28 November 2012 in case SA.33734, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/244293/244293_1400377_199_2.pdf;

of 28 November 2012 in case SA.33735, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/244292/244292_1400504_213_2.pdf;

of 28 November 2012 in case SA.33735, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/244807/244807_1400359_165_4.pdf;

of 28 November 2012 in case SA.35253, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/246568/246568_1406507_239_4.pdf;

of 20 December 2012 in case SA.34536, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/247029/247029_1413168_96_4.pdf;

of 20 December 2012 in case SA.35488, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/247030/247030_1413141_80_6.pdf;

of 20 December 2012 in case SA.35489, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/247032/247032_1423221_82_2.pdf;

of 20 December 2012 in case SA.35490, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/247031/247031_1413139_210_3.pdf.For DUTB see Commission decisions of 18 December 2013 in case SA.33229, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/245268/245268_1518816_267_7.pdf;

of 18 December 2013 in case SA.35709, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/248544/248544_1522897_264_2.pdf;

of 13 August 2014 in case SA.38228, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/251840/251840_1583043_100_2.pdf;

of 16 December 2014 in case SA.38522, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/252220/252220_1625594_223_2.pdf.

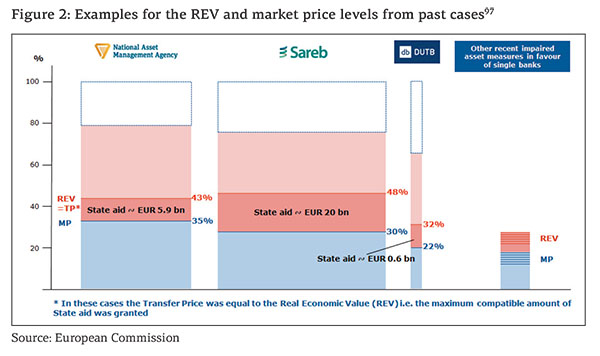

Figure 2 shows some historical examples of asset transfers approved by the Commission, comparing the level of the estimated market price and the REV to the gross book value, as well as reflecting the relative amounts of assets transferred. Apart from the three AMCs (i.e. NAMA, SAREB and DUTB) set up to buy impaired assets from several banks in the respective Member State, the Commission also approved several AMCs that only dealt with the impaired assets of individual banks. From these past cases one may draw the conclusion that on average the REV is usually 10 to 15 percentage points above the market price. However both values range widely across cases if expressed as a proportion of the gross book value. This observable difference in the respective levels illustrates that neither the estimated market price nor the REV may be grasped by uniform percentages. Ensuring consistency in the Commission’s approach requires assessing and taking into account all the important characteristics named above in each case that largely varies depending on the assets concerned, across Member States and the stage of the economic recovery as well. Based on the evidence available until now, these past REV valuations seem to be a rather correct estimation of the actual proceeds from the purchased impaired assets.

Conducting a valuation exercise that fulfils the requirements listed above may take a significant amount of time. This has given rise to complaints and criticism by Member States and beneficiaries alike, who would like the Commission to be able to determine the market price and the REV in a few days or weeks. While determining the REV for large portfolios of assets may indeed be time- and resource-consuming, it is an essential step in the process to ensure that Member States do not pay too much for the assets. It is the best way to ensure that the use of taxpayer money is minimized. Above all, any private market economy operator, before considering buying such type of illiquid and non-transparent assets would also require a detailed due diligence of the assets to determine their value before making any purchase.[27]Alternatively, if investors cannot perform such a due diligence they would require significant discounts to compensate for the uncertainty, leaving the banks who sell the assets with even greater … Continue reading In practice, the valuation exercise by the Commission services can be accelerated if it can draw from databases set up in the framework of other – regular or irregular – in-depth valuations such as the supervisory asset quality review (“AQR”). In this way, synergies can be realized leading to a reduction in the time and efforts spent on the valuation while maintaining the necessary degree of in-depth analysis.

4. Existence of aid and attachment point in case of asset guarantees

Asset guarantees form the second type of impaired asset relief measures. Contrary to asset transfers, the impaired assets remain in the bank’s balance sheet but the State commits to bear part of the losses in case of non-performance. Typically, the first losses will be fully borne by the bank. The State guarantee will kick-in and leads to payment to the bank only if the cumulative losses on the guaranteed portfolio exceed an amount defined in the guarantee contract (the “attachment point”). Thanks to the State guarantee, potential losses to be borne by the bank are capped, or at least reduced. In return, the bank pays a guarantee fee to the State.

The assessment whether such a measure constitutes State aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU follows the same logic as the one for asset transfers. The MEO principle is applied to test whether there is an advantage conferred upon the bank. In the case of asset guarantees, it translates to whether a normal market economy operator would provide a guarantee to the bank under the same terms. The important elements to consider in this context are the exposure of the State and the amount of the guarantee premium paid by the bank. Regarding the exposure of the State, one has to compare the attachment point with the likely cumulative losses which the guaranteed assets will generate over time. The likelihood that the measure involves State aid is lower if, based on the assessment of the likely losses of the guaranteed assets, the likelihood that the attachment point is reached is very low. Regarding the level of the guarantee fee, the higher it is, the lower the likelihood that the measure involves aid. If the likelihood that the attachment point is reached is very low and if the State receives a market-conform remuneration for the guarantee, the Commission would conclude that no advantage is granted to the bank, and therefore the measure is aid-free. However, if the outcome of the MEO assessment is that a private guarantor would only provide such a guarantee for a higher fee or would not provide it at all, the intervention constitutes State aid.

The previous paragraphs discussed the identification and quantification of State aid. Below, the requirements for any aid identified to be compatible with the internal market are explained. For an impaired asset guarantee, as for impaired asset purchases, the concept of REV should be applied. Therefore, asset guarantees must never cover the entire potential loss associated with a certain asset. The first losses should be fully borne by the bank; the guarantee shall only cover losses that exceed the attachment point. In line with the concept of REV, the attachment point should be set such that all the existing and likely losses are borne by the bank, i.e. by the first loss tranche. The State guarantee should only protect the bank against unlikely losses. In addition, in order to provide adequate incentives for the bank to reduce losses to the minimum even after the attachment point is reached, the bank shall also bear a given percentage of the losses that exceed the attachment point (residual loss-sharing or “vertical slice” retention by the bank), as illustrated in Figure 3. For an example of a guarantee with two tranches, see the State guarantee provided to Royal Bank of Scotland under the Asset Protection Scheme of the United Kingdom.[28]See Commission decision of 14 December 2009 in case N 422/2009 and N 621/2009, the full text of this decision can be found on: … Continue reading.For an example with three tranches, see the guarantee granted by Belgium on a portfolio of EUR 21 billion of assets.[29]See Commission decision of 12 May 2009 in case N255/2009 and N274/2009, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/231121/231121_1040770_72_1.pdf .

5. Additional State aid compatibility requirements applicable to impaired asset measures

When an impaired asset relief measure qualifies as State aid as explained above, it has, on top of the cap at REV, to respect a number of conditions in order to be declared compatible with the internal market by the Commission. Impaired asset relief measures are a form of restructuring aid and therefore have to meet the requirements of the Commission’s 2009 Restructuring Communication and of the 2013 Banking Communication. First, such measures can only be approved by the Commission on the basis of a restructuring plan that demonstrates how the bank’s long-term viability will be restored. Second, there needs to be a sufficient degree of burden sharing to limit the aid amount to the minimum possible. Thirdly, to ensure the level playing field with banks that do not receive State aid, additional measures limiting the distortions of competition need to be introduced. These three conditions are explained more in detail in the following paragraphs.

To comply with the Restructuring Communication, the restructuring plan must demonstrate how the bank intends to restore its long-term viability without State aid as soon as possible.[30]Restructuring Communication, recital 9. This condition is crucial to assure that State aid is not given to artificially keep banks alive that do not have a sustainable business model. Indeed, not only would this be a waste of taxpayers’ money and endanger financial stability, but it would also disrupt competition in the banking sector (in the event that the bank cannot be restored to viability, the restructuring plan should indicate how it can be wound up in an orderly fashion – in such case specific requirements for liquidation aid apply). The restructuring plan should identify the causes of the bank’s difficulties and the bank’s own weaknesses and outline how the proposed restructuring measures remedy the bank’s underlying problems.[31]Restructuring Communication, recital 10. The bank’s problems may among others concern its assets (e.g. significant drop in value due to their risk and stressed markets), its liabilities (e.g. overreliance on short-term market funding that suddenly dried up), or its cost base (e.g. which may have grown faster than its revenues, especially once the crisis hit). The Restructuring Communication requires that “restructuring should be implemented as soon as possible and should not last more than five years”[32]Restructuring Communication, recital 15..

Long-term viability is achieved when a bank is able to cover all its costs including depreciation and financial charges and provide an appropriate return on equity, taking into account the risk profile of the bank. The restructured bank should be able to compete in the marketplace for capital on its own merits in compliance with relevant regulatory requirements.[33]Restructuring Communication, recital 13. Long-term viability also requires that any State aid received is either redeemed over time, as anticipated at the time the aid is granted, or is remunerated according to normal market conditions, thereby ensuring that any form of additional State aid is terminated.[34]Restructuring Communication, recital 14. The sale of an ailing bank to another financial institution can contribute to the restoration of long-term viability, if the purchaser is viable and capable of absorbing the transfer of the ailing bank.[35]Restructuring Communication, recital 17. In such a situation, it should however be ensured that by selling the ailing bank, the buyer does not benefit from State aid.

In order to limit the amount of State aid to the minimum necessary, several conditions need to be respected before any State aid can be authorised. First, the 2013 Banking Communication requires that “[…] outflows of funds must be prevented at the earliest stage possible. Therefore, from the time capital needs are known or should have been known to the bank, the Commission considers that the bank should take all measures necessary to retain its funds“[36]2013 Banking Communication, recital 47.. For this reason, banks may among others not pay dividends or coupons, not make any acquisitions, and not engage in aggressive commercial practices. Second, the 2013 Banking Communication invites Member States to submit a capital raising plan, either before or together with the submission of the restructuring plan. According to the Communication the former plan “should contain in particular capital raising measures by the bank and potential burden sharing measures by the shareholders and subordinated creditors of the bank“.[37]2013 Banking Communication, recitals 29-30.

Banks should first try to finance the restructuring costs with their own resources and hence limit the amount of required State aid. For this reason, the restructuring plan should contain cost-cutting measures. In addition, the plan should also propose the sale of non-core activities as this not only generates resources but also reduces risk-weighted assets and hence results in lower capital requirements. To ensure that banks retain their capital rather than pay it out, for instance in the form of dividends or debt buybacks, the Commission puts restrictions on such transactions. Since the entry into force of the 2013 Banking Communication, burden sharing implies that an impaired asset relief measure – as any State recapitalisation – can only be granted after the shareholders and junior debtholders have contributed to cover the capital shortfall[38]2013 Banking Communication, recital 44.. In practice, this means that shareholders are written down or diluted while junior debtholders are converted (to equity) and/or written down. This burden sharing helps to absorb losses and/or contribute to restore the capital base thereby reducing the amount of required State aid.[39]The 2013 Banking Communication contains two exceptions to the burden sharing requirements. Burden sharing is not required where it would cause disproportionate results or where it would endanger … Continue reading In addition, it addresses the moral hazard problem that arises from bailing-out banks with public funds by shifting a significant part of the cost to the bank’s owners and junior debtholders.

As explained in recitals 29 and 30 of the Restructuring Communication, State aid can distort competition among banks both within and between Member States. For this reason, it is necessary to take measures limiting the distortions of competition in addition to the bank’s overall restructuring (which usually already entails closure of non-viable activities and adjustment of the pricing of new production to make it profitable) and the burden sharing by its investors (which addresses the moral hazard problem of State aid). The nature and form of such measures is dependent on the aid amount and the circumstances under which it was granted and the characteristics of the market(s) where the beneficiary bank operates.[40]Restructuring Communication, recital 30. For the assessment of the first criterion, the Commission considers both the absolute amount of aid and its size in relation to the bank’s risk-weighted assets.[41]Restructuring Communication, recital 31. As regards, the second criterion, the Commission takes into account the bank’s market share and considers whether effective competition is preserved.[42]Restructuring Communication, recital 32.

Three main categories of measures to limit distortions of competition, and hence to safeguard a level playing field among banks, can be distinguished. First, structural measures include the divestment of subsidiaries, branches, portfolios of customers, etc. and can also consist of putting constraints on the bank’s activities (e.g. limiting certain types of activity or in certain markets). Second, a number of behavioural measures are commonly imposed on the bank. This type of measures among others concerns acquisition bans, restrictions on pricing (to ensure State aid is not used to offer clients better rates than the bank’s competitors), and the prohibition to refer to the received State aid in its marketing. This category can also entail restrictions on management remuneration[43]See recitals 38-39 of the 2013 Banking Communication in this respect: “38. […] any bank in receipt of State aid in the form of recapitalisation or impaired asset measures should restrict the … Continue reading and other corporate governance requirements. Third, market opening measures can be required with a view to facilitating market entry and eventually to result in a more competitive, open market. Such measures may be taken at Member State level rather than at bank level.

Since the entry into force of the 2013 Banking Communication, these conditions need to be complied with before the aid is granted. For impaired asset relief measures this means that all of the abovementioned requirements need to be fulfilled at the moment of the asset transfer or the starting date of the guarantee. For this reason, the bank’s restructuring plan needs to be approved upfront by the Commission.[44] 2013 Banking Communication, recital 50. Restructuring plans can be drawn up at the level of the individual beneficiary bank or at the level of the merged entity in case several banks are being restructured and will be merged in a consolidation process. For instance, in Spain a number of Cajas was merged first and a restructuring plan was drawn up for the new entity.

6. Recent changes of the EU legal framework introduced by the BRRD and SRMR

In 2014, the European Parliament and the Council adopted the BRRD and the Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation (“SRMR”)[45]Regulation (EU) 806/2014 of 15 July 2014. Available online on: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014R0806 with the aim of ending “too big to fail” and creating a framework within which bank failures can be handled without the excessive use of taxpayers’ money. In line with this objective, the new legislative regime makes the application of the so-called bail-in tool the default approach by which it imposes losses and resolution costs primarily on the bank’s shareholders and creditors, thus limits the extent to which State resources may be used to finance restructuring.[46]For a summary of the recovery and resolution framework see also the accompanying press releases which can be found on: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-12-570_en.htm and … Continue reading

Under the BRRD, as a general rule the granting of “extraordinary public financial support”[47]Under Article 2(1)(28) of the BRRD, “extraordinary public financial support means State aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, or any other public financial support at supra-national … Continue reading, under which term State aid within the meaning of the TFEU falls, triggers resolution of the beneficiary bank.[48]Under Article 32 (1) of the BRRD, three cumulative conditions have to be met in order to place an institution under resolution, namely that (a) the institution is failing or likely to fail, (b) there … Continue reading However, Article 32(4)(d) BRRD also provides for three important exceptions[49]Article 32 (4) of the BRRD: “For the purposes of point (a) of paragraph 1, an institution shall be deemed to be failing or likely to fail in one or more of the following circumstances: […] … Continue reading under which granting extraordinary public financial support will not lead to resolution. Besides providing State guarantees on central bank liquidity assistance or on newly issued liabilities, the exception set out in Article 32(4)(d)(iii) BRRD, “an injection of own funds or purchase of capital instruments at prices and on terms that do not confer an advantage upon the institution”, commonly referred to as precautionary recapitalisation, is of particular relevance from the perspective of impaired asset relief measures.

Alternatively, Member States may grant State aid in the form of liquidation aid to banks that do not meet the conditions for resolution[50]Namely because the third condition for resolution that taking a resolution action is necessary in the public interest (Article 32(1)(c) of the BRRD) is not fulfilled. Pursuant to Article 32(5) of the … Continue reading in order to facilitate market exit by orderly winding them down while preserving financial stability.

In the context of a precautionary recapitalisation, public support has to be “limited to injections necessary to address capital shortfall established in the national, Union or SSM-wide stress tests, asset quality reviews or equivalent exercises conducted by the European Central Bank, the European Banking Authority or national authorities“[51]Article 32(4)(d) of the BRRD.. This means that incurred or likely losses cannot be covered, i.e. the State aid may only cover the additional capital shortfall stemming from the adverse scenario of the stress test, while capital needs stemming from the AQR and the baseline scenario have to be covered by private means.[52]See for example footnote 12 of Commission decision of 4 December 2015 in case SA.43365. The full text of this decision can be found on: … Continue reading Another important condition is that precautionary recapitalisation may only be granted after the Commission has granted its approval,[53] Article 32(4)(d) of the BRRD. i.e. the requirements concerning the restructuring plan and burden sharing described in Section need to be fulfilled upfront. Precautionary recapitalisations were approved by the Commission for example in the case of National Bank of Greece[54]See Commission decision of 4 December 2015 in case SA.43365. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/261565/261565_1733770_121_2.pdf and Piraeus Bank[55]See Commission decision of 29 November 2015 in case SA.43364. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/261238/261238_1733314_89_2.pdf .

Finally, for banks that are failing or likely to fail but for which resolution is not triggered (e.g. because it is not deemed to be in the public interest), the 2013 Banking Communication foresees the possibility of granting liquidation aid.[56]2013 Banking Communication, Section 6. The aim is to facilitate the market exit of such banks by orderly winding them down in the framework of the applicable national insolvency proceedings while mitigating the disturbance in the financial stability of the Member State concerned. The main requirements for liquidation aid are that shareholders and junior debt holders of the bank bear full losses and that the bank ceases to be an independent market player either by discontinuing any operation on the relevant market or by being fully integrated into another market player. As indicated in the latter case, the sale of part or the entirety of asset and/or viable businesses, for example the transfer of the deposit book, does not preclude the granting of liquidation aid. Nonetheless, the general principle of the EU State aid rules that aid must be limited strictly to the minimum necessary needs to be respected in any case.

7. Conclusion

Several EU Member States have, as part of a wider strategy and restructuring effort of their banking sectors, taken impaired asset relief measures. The State aid rules applicable to such impaired asset relief measures were drafted and adopted early 2009, at a time when several European banks, burdened by the rapidly decreasing and more and more uncertain value of structured credits, like US RMBS, asked support from their governments. Nowadays, some European banks are burdened by a different type of assets, namely plain vanilla corporate, SME, mortgage and consumer loans. However, the rationale and concepts on the basis of which the Impaired Asset Communication was built continue to be relevant and appropriate to assess any new impaired asset relief measure. For instance, it makes full sense to continue capping the purchase price of impaired assets at REV, which, as explained, is the present value of the future cash flows which can be expected from the assets, net of all workout costs. If the State was paying more than that price for the assets, it would be unlikely to recover the money injected. From the definition of REV, one can also conclude that, if a Member State would introduce reforms which, in practice, are able to shorten and to reduce the cost of workout of NPLs, this would by construction increase the REV of the assets. It would also most probably increase their market price, since private investors would also be able to recover more money from the processing of the NPLs. The concepts of REV and estimated market price – which are at the basis of the State aid analysis of impaired asset relief measures – are therefore not at all a disincentive to implement structural reforms facilitating and reducing the cost of processing NPLs, to the contrary.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | For detailed statistics on non-performing loans see for example the EBA Risk Dashboard. This publication is available online on: http://www.eba.europa.eu/risk-analysis-and-data/risk-dashboard. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For instance, Santander, BBVA, and La Caixa managed their NPLs internally. |

| ↑3 | See: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT. |

| ↑4 | More guidance on these conditions can be found in the Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) TFEU. This document can be found on DG Competition’s website, see: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/modernisation/notice_aid_en.html. |

| ↑5 | See Commission decision of 10 February 2016 in case SA.38843. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/260961/260961_1733345_231_2.pdf |

| ↑6 | See Commission decision of 10 February 2016 in case SA.43390. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/262816/262816_1744018_70_2.pdf |

| ↑7 | This requirement is laid down in Article 108 (3) of the TFEU. |

| ↑8 | The documents that make up this framework can be found on DG Competition’s website, see: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/legislation/temporary.html |

| ↑9 | In particular it concerns: the 2008 Recapitalisation Communication, the 2009 Impaired Assets Communication, the 2009 Restructuring Communication, the 2010 Prolongation Communication, the 2011 Prolongation Communication and the 2013 Banking Communication. |

| ↑10 | The State aid scoreboard which reports aid expenditure made by the Member States, contains a dedicated table on State aid to financial institutions in the years 2008-2015, by type of aid instrument and can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/scoreboard/index_en.html |

| ↑11 | Impaired Assets Communication, recital 15. |

| ↑12 | For more detail on the concept of REV, see the explanation in Section . |

| ↑13 | Directive 2014/59/EU of 15 May 2014. Available online on: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0059 . |

| ↑14 | For simplicity, the condition of imputability to the State will not be discussed in this article. |

| ↑15 | Commission Notice on the notion of State aid, Section 4.2. |

| ↑16 | Commission Notice on the notion of State aid, recital 74. |

| ↑17 | Commission Notice on the notion of State aid, recital 78. |

| ↑18 | Impaired Assets Communication, footnote 2 to recital 20 (a), recital 39. |

| ↑19, ↑20 | Impaired Assets Communication, recital 40. |

| ↑21 | However as an exception to this general principle, recital 41 of the Impaired Assets Communication notes that Member States may in some circumstances decide that it is necessary to use a transfer price that exceeds the REV of the assets. In such cases, the amount of State aid is larger which the Commission can only accept if far-reaching restructuring measures are taken. Furthermore, conditions need to be introduced allowing the recovery of this additional aid at a later stage, for example through claw-back mechanisms. |

| ↑22 | Notion of State Aid Notice, recitals 84, 86-96. |

| ↑23 | Notion of State Aid Notice, recitals 85, 97-100. |

| ↑24 | Notion of State Aid Notice, recitals 85, 101. |

| ↑25 | Assets were to be purchased by MARK at a transfer price determined by the formulae that the Commission approved to result in a price that did not exceed the market price, therefore the measure was aid-free. |

| ↑26 | Impaired Assets Communication, recitals 40-43 and Annex IV. |

| ↑27 | Alternatively, if investors cannot perform such a due diligence they would require significant discounts to compensate for the uncertainty, leaving the banks who sell the assets with even greater losses. |

| ↑28 | See Commission decision of 14 December 2009 in case N 422/2009 and N 621/2009, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/233798/233798_1093298_30_2.pdf |

| ↑29 | See Commission decision of 12 May 2009 in case N255/2009 and N274/2009, the full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/231121/231121_1040770_72_1.pdf |

| ↑30 | Restructuring Communication, recital 9. |

| ↑31 | Restructuring Communication, recital 10. |

| ↑32 | Restructuring Communication, recital 15. |

| ↑33 | Restructuring Communication, recital 13. |

| ↑34 | Restructuring Communication, recital 14. |

| ↑35 | Restructuring Communication, recital 17. |

| ↑36 | 2013 Banking Communication, recital 47. |

| ↑37 | 2013 Banking Communication, recitals 29-30. |

| ↑38 | 2013 Banking Communication, recital 44. |

| ↑39 | The 2013 Banking Communication contains two exceptions to the burden sharing requirements. Burden sharing is not required where it would cause disproportionate results or where it would endanger financial stability. Until now, the latter exception has not been applied while the former has only been used in a few cases. |

| ↑40 | Restructuring Communication, recital 30. |

| ↑41 | Restructuring Communication, recital 31. |

| ↑42 | Restructuring Communication, recital 32. |

| ↑43 | See recitals 38-39 of the 2013 Banking Communication in this respect: “38. […] any bank in receipt of State aid in the form of recapitalisation or impaired asset measures should restrict the total remuneration to staff, including board members and senior management, to an appropriate level. That cap on total remuneration should include all possible fixed and variable components and pensions, and be in line with Articles 93 and 94 of the EU Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV). The total remuneration of any such individual may therefore not exceed 15 times the national average salary in the Member State where the beneficiary is incorporated or 10 times the average salary of employees in the beneficiary bank. Restrictions on remuneration must apply until the end of the restructuring period or until the bank has repaid the State aid, whichever occurs earlier. 39. Any bank in receipt of State aid in the form of recapitalisation or impaired asset measures should not in principle make severance payments in excess of what is required by law or contract.” |

| ↑44 | 2013 Banking Communication, recital 50. |

| ↑45 | Regulation (EU) 806/2014 of 15 July 2014. Available online on: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32014R0806 |

| ↑46 | For a summary of the recovery and resolution framework see also the accompanying press releases which can be found on: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-12-570_en.htm and http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STATEMENT-14-119_en.htm; and the publication on frequently asked questions which can be found on: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-14-297_en.htm |

| ↑47 | Under Article 2(1)(28) of the BRRD, “extraordinary public financial support means State aid within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, or any other public financial support at supra-national level, which, if provided for at national level, would constitute State aid, that is provided in order to preserve or restore the viability, liquidity or solvency of an institution or entity referred to in point (b), (c) or (d) of Article 1(1) or of a group of which such an institution or entity forms part”. |

| ↑48 | Under Article 32 (1) of the BRRD, three cumulative conditions have to be met in order to place an institution under resolution, namely that (a) the institution is failing or likely to fail, (b) there is no reasonable prospect that any alternative private sector measures, would prevent the failure of the institution within a reasonable timeframe and (iii) a resolution action is necessary in the public interest. As a general rule, receiving extraordinary public financial support triggers the qualification as failing or likely to fail (see Article 32 (4) of the BRRD cited under footnote 122), thus is taken into account in relation to the first condition, and triggers resolution only if the other two conditions are also met. |

| ↑49 | Article 32 (4) of the BRRD: “For the purposes of point (a) of paragraph 1, an institution shall be deemed to be failing or likely to fail in one or more of the following circumstances: […] (d) extraordinary public financial support is required except when, in order to remedy a serious disturbance in the economy of a Member State and preserve financial stability, the extraordinary public financial support takes any of the following forms: (i) a State guarantee to back liquidity facilities provided by central banks according to the central banks’ conditions; (ii) a State guarantee of newly issued liabilities; or (iii) an injection of own funds or purchase of capital instruments at prices and on terms that do not confer an advantage upon the institution, where neither the circumstances referred to in point (a), (b) or (c) of this paragraph nor the circumstances referred to in Article 59(3) are present at the time the public support is granted. In each of the cases mentioned in points (d)(i), (ii) and (iii) of the first subparagraph, the guarantee or equivalent measures referred to therein shall be confined to solvent institutions and shall be conditional on final approval under the Union State aid framework. Those measures shall be of a precautionary and temporary nature and shall be proportionate to remedy the consequences of the serious disturbance and shall not be used to offset losses that the institution has incurred or is likely to incur in the near future. Support measures under point (d)(iii) of the first subparagraph shall be limited to injections necessary to address capital shortfall established in the national, Union or SSM-wide stress tests, asset quality reviews or equivalent exercises conducted by the European Central Bank, EBA or national authorities, where applicable, confirmed by the competent authority.” |

| ↑50 | Namely because the third condition for resolution that taking a resolution action is necessary in the public interest (Article 32(1)(c) of the BRRD) is not fulfilled. Pursuant to Article 32(5) of the BRRD “a resolution action shall be treated as in the public interest if it is necessary for the achievement of and is proportionate to one or more of the resolution objectives referred to in Article 31 and winding up of the institution under normal insolvency proceedings would not meet those resolution objectives to the same extent”. |

| ↑51 | Article 32(4)(d) of the BRRD. |

| ↑52 | See for example footnote 12 of Commission decision of 4 December 2015 in case SA.43365. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/261565/261565_1733770_121_2.pdf |

| ↑53 | Article 32(4)(d) of the BRRD. |

| ↑54 | See Commission decision of 4 December 2015 in case SA.43365. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/261565/261565_1733770_121_2.pdf |

| ↑55 | See Commission decision of 29 November 2015 in case SA.43364. The full text of this decision can be found on: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/261238/261238_1733314_89_2.pdf |

| ↑56 | 2013 Banking Communication, Section 6. |