The current overhang of NPLs in Europe is not exceptional in a historical perspective. However, despite the wealth of experience in NPL resolution accumulated after earlier crisis episodes, resolving Europe’s NPL problem continues to be a thorny issue. Difficulties reflect the chronic nature of the NPL malaise this time round but also the widely differing perceptions about the upside that NPLs may still present. For these reasons, NPL stocks are unlikely to decline fast and the costs of delayed action continue to accumulate. A number of promising resolution schemes – involving specialised asset management companies, specialised servicers, and/or securitisations – have been put forward. To be effective, these schemes will require hard policy choices to be made.

1. Introduction

Across much of Europe, and both within and outside of the Eurozone, non-performing loans (NPLs) continue to loom large almost a decade after the 2008-09 global financial crisis. This NPL overhang is hardly new or unique: high NPL ratios have been observed in the aftermath of many previous financial crises and economic downturns. Moreover, various approaches to cleaning up bank balance sheets have been successfully tried and tested in markets ranging from Malaysia to Sweden. Why then, given this wealth of experience in NPL resolution, is it proving so hard to resolve non-performing loans this time round? And what can be done to clean up the balance sheets of European banks? This short article examines these questions against the background of recent European policy discussions as well as the global experience with NPL resolution over the past two decades.

2. Europe’s NPL challenge in a comparative perspective

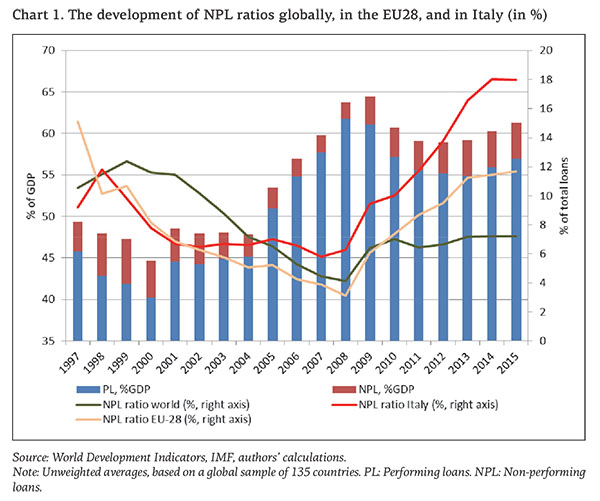

Data on non-performing loans are notoriously difficult to compare across place and time. The definition of what constitutes a non-performing loan varies widely across countries and so does the quality of reporting by banks and their supervisors. With these caveats in mind, a look at the global NPL picture since 1997 is nonetheless insightful. The analysis follows Balgova, Nies and Plekhanov (2016) and is largely based on data reported in the World Development Indicators of the World Bank.

Chart 1 indicates that current NPL levels in the EU are not exceptional on average. The global (unweighted) average NPL ratio in a sample of over 130 countries is around 7.5 per cent, slightly above the average of 7.1 per cent in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe (CESEE) as well as the European Union (EU)’s weighted 5.5 per cent. These averages are well below the peak of around 12 per cent for the global sample in 1999 in the aftermath of the Mexican, Asian and Russian crises. That 1999 peak in fact corresponds to the level of today’s unweighted average in the EU-28 (the picture is broadly similar if we look at median rates).

What is different this time round, however, is the profile of the rise and fall in NPLs. The NPL problem currently is more “chronic” while in the past it tended to be more “acute”. For instance, while the average NPL ratio peaked in 1999 (almost immediately after the Asian and Russian crises) it subsequently fell swiftly and persistently. It eventually bottomed out at 4 per cent just before the 2008 crisis. The pattern was similar in the Nordic countries in the early 1990s. In contrast, the average NPL ratio globally and in many European countries has been edging up gradually but persistently ever since the 2008 crisis. In the EU-28, this rise has been steeper than was the case globally, especially in Italy which is now responsible for about 30 percent of the NPL stock in the Eurozone.

3. Passive muddling through versus active resolution

Although this aspect is often overlooked in policy discussions, various countries managed to ‘passively’ grow out of their NPL problems on the back of a supportive external environment and/or the resumption of rapid credit growth. In such cases, NPL ratios may fall organically as total credit (the denominator of the ratio) expands. Moreover, firms that were not in a position to service their obligations may start generating sufficient cash flow to repay their debts in part or in full. In China, for instance, rapid economic growth has played a major role in supporting a steady decline in the (officially reported) NPL ratio from almost 30 per cent in 2002 to just 1 per cent in 2012. While China also established several specialised asset-management companies to transfer non-performing assets from the balance sheets of the four largest banks, supportive growth conditions and rapid credit expansion arguably made a more important contribution to the drop in NPL ratios.

Unfortunately, a systematic examination of episodes of NPL reductions indicates that cases where an NPL overhang is successfully resolved on the back of a credit boom and a supportive external environment are not common (Balgova et al., 2016). Moreover, such occurrences tend to happen in countries with low per capita income levels, low debt-to-GDP ratios and high inflation, where prospects for prolonged rapid growth are more likely. These factors for instance played a role in driving down NPL ratios in the new EU member states in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

In cases where a passive, organic strategy to grow out of an NPL problem is unlikely to be successful, a more active and decisive form of NPL resolution is needed. Unfortunately, such action is often delayed by a lack of incentives for the main stakeholders involved. In many cases, banks do not have the incentive to resolve NPLs as they expected to recover more than what is priced by the market. Corporate managers do not have an incentive either as widespread corporate restructuring often requires a change in management. Finally, regulators may delay NPL resolution because they are wary of disturbing fragile economic recoveries too soon. For all these reasons, NPL reductions underpinned by policy action typically only start when NPL ratios exceed 22 per cent (Balgova et al., 2016) – a level surpassed in Cyprus and Greece but not in Italy (data as of early 2017).

4. Why is tackling NPLs proving so difficult in Europe?

Large and persistent NPL stocks continue to hamper the post-crisis recovery as they drag on economic growth, even when fully provisioned (as is the case in many European economies), since they absorb managerial time, both in banks and corporates, and render performing loans more expensive. Why has a solution to Europe’s NPL problem been so difficult to pin down? We discuss seven important factors in turn:

First, an important component of a successful NPL resolution scheme is the establishment of a market for distressed debt. However, NPL valuations that attract buyers may be substantially lower than those that tempt banks to sell their exposures. This bid-ask spread reflects differences in discount factors arising from diverging funding costs; different levels of risk aversion; different access to or assessment of data, and different perceptions about the upside in case of improving economic conditions. In particular, with record-low interest rates in the wake of the crisis, the difference between lending rates, which banks often use as a discount factor, and the required return on equity of asset-management companies (typically in the region of 15 per cent) may be particularly high. This leads to wide gaps in estimated net present value even for identical future cash flows. As a result, markets for distressed debt often do not emerge spontaneously and regulatory pressure may be needed to incentivise NPL transfers. Yet, in some cases stricter rules may also discourage NPL sales. For instance, if banks are required to mark-to-market their debt portfolios based on the completed sales of comparable NPLs, they may be further discouraged from participating in NPL sales at lower prices (Fell et al., 2016).

Second, the creation of a market for distressed debt is often hampered by the high cost of due diligence, especially in smaller European countries, with smaller potential volume of NPL sales. This is because NPL investors are often large US companies, with little existing local knowledge about the legal and judiciary system, regulatory resolution framework, or local companies and real estate. Investing in due diligence is costly for these investors, particularly if the prospective NPL market is not large enough to justify it. Standardisation of data prepared for such global NPL investors, and raising the skills of local NPL sellers in preparing and presenting standardised data, can help to overcome these problems and help to attract a larger pool of investors. Standardisation of resolution frameworks across Europe, as much as possible, can also be of help.

Third, banks have clear incentives to offload the worst exposures as part of a resolution package. Banks, as the originators, have far more inside information about loan quality than outside investors. The presence of asymmetric information creates a classic market failure where the package of NPLs on offer at any given price is of a quality below what is needed to justify that price. This may call for a solution in which banks retain some of the downside associated with the non-performing loans after sale. In addition, uniform valuation principles should be applied to increase transparency. This, however, may be easier for straightforward loans, such as real-estate projects, than for more idiosyncratic borrowers such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which for instance make up a large proportion of Italian bad loans.

Fourth, the role of an “upside” is typically overlooked. If NPLs remain on banks’ own balance sheets, banks retain an upside in case of an organic, demand-driven resolution of the NPL problem. In contrast, if loans are sold to a special-purpose vehicle at a fixed price, any upside will rest with the buyer. An upside due to a strengthening economic outlook is often regarded as likely by banks or policymakers, in some cases based on earlier experiences (notably in Central and South-Eastern Europe). For instance, recent studies indicate that sustained economic growth of just 1.2 per cent would be sufficient to let Italian NPLs steadily decline (Mohaddes et al., 2017). At first sight this appears to be imminently achievable. Yet, the last episode when Italy’s economy sustained a rate of growth in excess of 1.2 per cent for 3 years or more (1994-2001) ended 16 years ago. This puts the odds of a favourable growth dynamic that would take care of the NPL problem into perspective. The example also highlights why any solutions to a chronic NPL problem may remain elusive: the potential upside of a “muddling through” approach may appear more appealing to banks, and perhaps also their regulators, than is warranted based on facts.

Fifth, banks continue to experience difficulties in raising fresh capital from private sources (Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2016). In Europe in particular, the low profitability of banks in mature banking systems (often with excess capacity) makes it hard for banks to replenish capital. This stands in stark contrast with banks in South-East Asia in the 1990s that could use retained profits to bolster their capital ratios (Bruno et al., 2017), or in Japan in 2003, where banks were able to access fresh capital at short notice (Farrant et al., 2003). Note also that schemes in which banks retain some downside of NPL resolution are likely to require additional fresh capital to underpin contingent or direct liabilities (unless, of course, NPLs are sufficiently provisioned).

Sixth, and related to the previous point, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) imposes strict restrictions on the use of public funds in bank recapitalisations. The long run aim of the directive is to reduce moral hazard and make a repeat accumulation of bad debts less likely. In the short run, however, it limits options for state-sponsored recapitalisation even in countries where there may be enough fiscal space. And even if such recapitalisation could deliver ex-post profits to the taxpayer.

Seventh and finally, asset management companies (AMC), special purpose vehicles (SPVs), and specialised NPL servicers tend to bring higher value where they can best leverage their work-out expertise. In case of AMC or SPVs this is typically in the case of real estate or real-estate-backed loans, or in case of fragmented debt, whereby one company borrows from multiple banks. Synergies in the case of other corporate (and retail) loans may be more limited – yet corporate loans account for a major part of the NPL stock in a number of European countries. Specialised NPL servicers, both local and regional, may nevertheless turn out to be essential, since widespread NPL resolutions create a large demand for corporate restructuring, foreclosure, collateral sales and other relevant skills. Such skills are often in short supply in specific countries and represent a major bottleneck for a sustainable NPL resolution.

5. Required features of resolution schemes

A strategy for dealing with NPLs typically involves four components: tightening of supervisory policies; insolvency reforms; skills capacity building; and the development of markets for distressed debt (Aiyar et al., 2015; Garrido et al., 2016). The first three components are crucial and yield dividends over the longer term. The effect of transferring distressed debt to specialised asset management or servicing companies is more immediate and much of the policy debate has focused on such companies.

A distressed debt market may have (privately-funded) bad banks at its core or it may rely on a securitisation scheme (Bruno et al., 2017). For a securitisation scheme to work, market participants need to share fairly upbeat assumptions about the recovery rates of currently non-performing loans. These assumptions need to be not only shared but also realistic – to avoid the pitfalls of subprime mortgage securitisation in the run-up to the 2008 crisis. In this regard, it is imperative to collect historical evidence on recovery rates from a variety of NPL episodes across countries and time periods. If they validate the model assumptions, securitisation can be a promising approach, in particular if governments can buy or guarantee junior tranches.

Most of the current policy proposals are structured in a way that banks fully forego any upside associated with NPLs on their books. In certain proposals, banks also retain some of the downside in the form of clawback provisions. Such provisions are designed to address the aforementioned asymmetric information problem by incentivising banks not to offload predominantly hopeless loans (see, for instance, Haben and Quagliariello, 2017). In practice, however, clawback provisions may be challenging to implement. They may of course also reduce the incentives of the SPV to put effort into loan workout.

An alternative approach is to leave the banks some upside potential, in order to help bridge the gap between bid and ask prices in the market. This can take the form of a (minority) equity stake by a bank in the AMC or SPV. While such equity stakes can provide banks with additional incentives to transfer NPLs – and in particular NPLs that may be viable and benefit from AMC workout expertise – they may also increase the amount of fresh capital that the banks need to raise (as part of this capital would indirectly be used to underpin the purchase of equity in AMCs). This capital may (in part) come from public sources, provided this can be compliant with the BRRD.

Finally, whatever the structure of the distressed debt market, the issue of the composition of NPLs in Europe remains. AMCs may be well suited for real-estate loans or other debt with strong collateral, or to ensure managing control in distressed companies with fragmented debt. However, even when transferred to the balance sheets of special purpose vehicles, loans of small and medium-sized businesses remain a heavy burden on these firms’ balance sheets and therefore a drag on economic recovery. Straight write-off of such exposures, in case of viable companies, may in some cases be an economically and socially more attractive option – albeit, once again, one that would require higher amounts of fresh capital upfront, both for banks and for restructuring of such viable companies.

Alternatively, there are views that a public and centralised asset management company could be set up at the level of the Eurozone (Beck and Trebesch, 2013) to deal with the legacy of the Eurozone crisis in case private schemes are unable to overcome the information asymmetries and other problems associated with a private market in non-performing debt. Such an international asset management company may be better at exploiting economies of scale (as national schemes are no longer necessary) and at dealing with cross-border NPLs. In addition, a Eurozone solution could be defended on the grounds that banks in this zone have a common regulator and access to a common lender of last resort while national authorities can do little to incentivise banks to deal with NPLs (Beck, 2017).

Critics of such a scheme have pointed out that it may bring about moral hazard as NPLs are unevenly spread across the Eurozone countries, while the burden is equally shared between taxpayers. Such a scheme would, of course, also not help to reduce the significant NPL burden of many countries outside the Eurozone, especially in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe (CESEE). Additional measures would need to be taken in this region, in particular since the smaller absolute size of their NPL markets renders attracting private NPL investors even more challenging, while at the same time more necessary, given that limited fiscal space mostly rules out public solutions.

Many CESEE countries have coordinated their actions on NPL resolutions through the so-called Vienna Initiative platform[1]A public-private platform for coordinating private banks, international financial institution, and home and host authorities in CESEE., and its NPL Initiative[2]See http://npl.vienna-initiative.com/. This initiative focuses on three major areas: (i) increasing transparency of NPL resolution frameworks, by creating credible action plans for NPL resolution in each country, including a range of legal reforms (such as bankruptcy laws and out-of-court restructurings), tax reforms, and regulatory reforms; (ii) capacity building (workout professionals, judiciary, insolvency professionals); and (iii) knowledge sharing on best practices in NPL resolution, through the NPL Initiative website, a regularly published NPL Monitor as well as regular cross-regional discussions.

Partly because of the NPL Initiative’s efforts, NPL ratios in CESEE have dropped by almost a percentage point in the year to June 2016 when they stood at 7.1 per cent. This downward trend has continued in 2017. Most of this drop has been the result of private NPL sales. But more needs to be done, particularly by addressing skill shortages. Given that most of the NPLs in CESEE region are in the corporate rather than retail sector, skills in the area of corporate restructuring and wind-down are a particular bottleneck. A way to address this is through the faster development of dedicated local or regional NPL servicers, which could exploit economies of scale in dealing with corporate restructurings and wind-downs.

6. Conclusion

In Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, a long-term effort to resolve large NPLs (partly coordinated through the regional Vienna and NPL Initiative platforms) has recently started to bear fruit. The efforts were based on the implementation of transparent action plans developed by the authorities, often in collaboration with international financial institutions, banks and the real sector. These actions included reforms in legal, regulatory and fiscal areas, followed by a decisive regulatory push. Given that limited fiscal space mostly constrained public-funded solutions, the key condition for falling NPLs was the ability to attract international and local NPL investors to these countries. Transparency of action plans and the availability of relevant data helped and continues to be crucial in these efforts.

Since most NPLs in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe are in the corporate segment, a sustainable resolution not only requires removing NPLs from banks’ balance sheets, but also a lengthy process of corporate restructurings and wind-downs, which is still ahead of us. For the success of the latter, building up skills and capacities of workout professionals, judiciary and insolvency professionals will be key. In that respect, developing specialised NPL servicers, both local and regional, will be essential to optimise the use of scarce specialized human resources in this part of the world.

References

Aiyar, S., Bergthaler, W., Garrido, J., Ilyina, A., Jobst, A., Kang, K., Kovtun, D., Liu, Y., Monaghan, D., and Moretti M. (2015). A Strategy for Resolving Europe’s Problem Loans. IMF Staff Discussion Note No 15/19, Washington, DC, International Monetary Fund.

Avgouleas, E., and Goodhart, C. (2016). An Anatomy of Bank Bail-ins: Why the Eurozone Needs a Fiscal Backstop for the Banking Sector. European Economy – Banks, Regultion, and the Real Sector, 2, 75-90.

Balgova, M., Nies, M., and Plekhanov, A. (2016). The economic impact of reducing non-performing loans. EBRD Working Paper No. 193, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, London.

Beck, T., and Trebesch, C. (2013). A bank restructuring agency for the Eurozone – cleaning up the legacy losses. VoxEU.org, 18 November.

Beck, T. (2017). An asset management company for the Eurozone: Time to revive an old idea. VoxEU.org, 24 April.

Bruno, B., Lusignani, G., and Onado, M. (2016). A securitisation scheme for resolving Europe’s problem loans. Mimeo, 7 December.

Cucinelli, D. (2015). The Impact of Non-Performing Loans on Bank Lending Behaviour: Evidence from the Italian Banking Sector. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 8, 59-71.

De Haas, R., and Knobloch, S. (2010). In the wake of the crisis: dealing with distressed debt across the transition region. EBRD Working Paper No. 112, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, London.

Farrant, K., Markovic, B., and Sterne, G. (2003). The Macroeconomic Impact of Revitalising Japanese Banking Sector. Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, Winter 2003.

Fell, J., Grodzicki, M., Martin, R., and O’Brien, E., (2016). Addressing market failures in the resolution of non-performing loans in the euro area. Financial Stability Review, November, European Central Bank, Frankfurt.

Garrido, J., Kopp, E., and Weber, A. (2016). Cleaning up Bank Balance Sheets: Economic, Legal, and Supervisory Measures for Italy. IMF Working Paper No. 16/135, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

Haben, P., and Quagliariello, M. (2017). Why the EU needs an asset management company. Centralbanking.com, 20 February.

Mohaddes, K., Raissi, M., and Weber, A., (2017). Can Italy Grow Its Way Out of the NPL Overhang? A Panel Threshold Analysis. IMF Working Paper No. 17/66, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | A public-private platform for coordinating private banks, international financial institution, and home and host authorities in CESEE. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See http://npl.vienna-initiative.com/ |