The recovery of the Eurozone (EZ) economy has made even more pressing the tackling of its debt overhang with the bulk of over 1 trillion Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) concentrated in the more vulnerable economies of the EZ periphery. There is clearly a need to adopt a more radical approach to resolving NPLs than merely augmenting supervisory tools and national legal frameworks. The discussion about the feasibility of country-based or Pan-European Asset Management Companies (AMCs) to tackle legacy NPLs has recently intensified. Yet political objections premised on fears of debt mutualisation, the structural and legal questions surrounding the possible establishment of AMCs, and differing recovery rates and levels of market transparency within the EZ have led to the dismissal of the idea by the European Council. This article discusses the merits and shortcomings of AMCs in tackling NPLs and proposes a comprehensive structure for a Pan-European “bad bank” with virtually ring-fenced country subsidiaries to ensure burden sharing without debt mutualisation. The proposed “bad bank” structure intends to resolve a host of governance, valuation, and transparency problems that would otherwise surround a “bad bank” solution. Also, the proposed scheme is in effecoctive compliance with the EU state aid regime and could lead, if implemented, to the alleviation of the EZ debt overhang to stimulate credit growth.

1. Introduction

The gradual recovery of the Eurozone (EZ) economy has made even more pressing the tackling of legacy Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) in the EZ. Authoritative sources (Aiyar et al. 2015) have pointed out that the huge load of NPLs standing at more than 1 trillion EUR at ECB’s latest estimation is clearly a serious impediment on EZ growth, especially as the bulk of them is concentrated in the more vulnerable economies of the EZ periphery. So far, most countries concerned have been slow in tackling the NPL problem. This has highlighted the need to adopt more radical steps than merely augmenting the supervisory tools and national legal frameworks dealing with NPLs, though the latter have been necessary and essential reforms. It also explains why the discussion about the feasibility of country-based or Pan-European Asset Management Companies (AMCs) that will purchase, securitise, workout, and dispose the bulk of legacy NPLs has intensified since last year (e.g., Bruno et al. 2017; Enria 2017; Haben, Quagliarello 2017; ECB 2016). For their proponents, AMCs offer the fastest and most radical remedy for Eurozone’s NPL problem. Yet political objections premised on fears of debt mutualisation within the EZ, and the structural and legal questions surrounding the possible establishment of a Pan-European Fund or country-based AMCs, led to the dismissal of the idea in the ECOFIN’s informal meeting in Malta in April 2017.Amongst the first contributions to this debate was a proposal by the authors of this note sketching a form of privately funded AMC backed by a fiscal backstop to tackle EZ bank NPLs (Avgouleas, Goodhart 2016). In this note we revisit the issue with a view to painting a more detailed picture of our proposal. But before we set out our proposal it is apposite to summarize the structural and legal obstacles that the process/effort to tackle EZ NPLs through an AMC would face. The structural problems are more, or less, the same that have prevented the creation of a liquid secondary market for NPLs in Europe. They are in summary:

(a) bankruptcy regimes with a pro-debtor bias: this is a shortcoming that is gradually being remedied through the introduction of out-of-court procedures and a code of conduct for NPL settlement, aiding the recovery process;

(b) long recovery times and high recovery costs, which differ on a country-to-country basis, (even if the NPL laws are increasingly being harmonised), due to differing legal and judicial cultures and different degrees of restructuring skills on the business side as well as variable legal infrastructure effectiveness;

(c) low and differing levels of transparency, which, first, create “market for lemons”[1]Akerloff (1970). conditions in the secondary market and intensify bid ask spread discrepancies;

(d) appreciable disparities between net book value (ex provisions) and market value, mostly as a result (a)-(c) factors above which amount to a major disincentive to clean up the pile of NPLs in the EZ, since a sale way below net book value would generate serious capital write offs, [2]For a very comprehensive exposition of this problem see Bruno, B, G. Lusignani, and M. Onado (2017).possibly triggering the bail-in process under the BRRD (Avgouleas, Goodhart 2016);

(e) EZ banks’ low profitability, which, in turn is partly due to the burden NPLs place on bank balance sheets, and in part to a sluggish interest rates. Under these conditions there is little, or no, prospect of accumulating sufficient retained profit to absorb losses from the writing down of NPL values.

These structural obstacles are complemented by the constraints posed by the EU State Aid laws and the EU Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive’s (BRRD) near complete prohibition of making available public funding to an ailing bank, including resorting to public money to fund bank recapitalisation in resolution, unless, in the latter case, a round or rounds of creditor bail-ins have taken place first.

The interaction of these structural obstacles and the BRRD constraints have also less tangible, but evident, behavioural consequences in the form of regulatory and bank management forbearance (Avgouleas, Goodhart 2016). Where the problem of NPLs is systemic affecting several banks (e.g., Greece, Italy), bank management and their regulators may wish to avoid, at least for a time, the bitter pill of capital write offs in fear of the institutional and systemic consequences that a wave of bank bail-ins could give rise to.

In the remainder of our note we first set out in summary the key benefits and costs for using country-based or Pan-European AMCs to tackle EZ NPLs, and then we give a detailed description of our proposal and how we consider the above challenges could be met by our plan.

2. AMCs and NPL Resolution –Pros and Cons

In a nutshell, the advantages of using AMCs to clean up bank balance sheets are the following:

(a) The solution can be quite radical and may be the best way to provide a fiscal backstop to the banking sector; the ensuing virtuous cycle of renewed bank credit, strengthened economic growth, and increased bank profitability has often worked miracles for NPL resolution and the financial results of AMC “bad banks”. Such burden sharing and attendant financial engineering has been successfully employed in a variety of NPL transfer schemes during the Asian crisis of late 1990s (Arner, Avgouleas, Gibson 2017);

(b) AMCs can secure economies of scale in tackling NPLs, especially where a large part of the AMC’s portfolio comprises corporate NPLs, which, in general, are harder to restructure than receivables NPLs. In specific, AMCs can provide economies of scale in hiring professionals with turnaround skills or negotiating with private equity firms, securing thus higher recovery values;

(c) AMCs can provide economies of scale vis-à-vis the issuance and marketing of tranches of debt collateralised with distressed loans, widening the size of the secondary market for distressed debt and making it more liquid;

(d) Finally, with an AMC it could be easier to implement debt to equity swaps, due to minimum or limited capital requirements, a distinct disadvantage facing banks engaging in this method of debt write offs.

This encouraging picture is not uniform. The use of a country AMC to resolve the Scandinavian banking crisis and the Asian financial crisis proved to be a success. On the other hand, the post-2008 experience in Europe has been more mixed. From the three countries that have used “bad banks” only Ireland’s NAMA shows encouraging signs of final value recovery and that may also be down to the underlying strength of the Irish economy.

The use of AMCs to resolve NPLs can face important challenges which in the main can be summarised as follows:

(a) the governance issue – mostly relating to a fear of cherry picking, or that the bad bank will be used to restructure loans to related parties at favourable terms, or to warehouse and hide worthless assets. Debt to equity swaps may encounter a similar problem resulting in the rescue of “zombie” companies” (IMF, 2016 on the challenges of Chinese scheme);

(b) limited transparency and uncertainty about the quality of bank disclosures and due diligence can give rise to a “market for lemons” situation;

(c) asset valuation – the choice of measures to be employed to calculate NPL value, e.g., market value, book value, net book value, or long-term economic value is a matter of great importance both for the success of the scheme and the distribution of losses. Of course, this is no simple matter as the rate of NPL recovery, especially vis-à-vis corporate and real estate loans, is also dependent on the prevailing conditions of demand in the market and the state of the macroeconomic cycle;

(d) ultimate loss absorption – which party will absorb any losses on liquidation and winding up.

In addition, bank management’s and owners’ incentives are crucial, especially since regulatory “coercion” may not be able to offer immediate results or at least not without running the risk of firesales. Either the bank’s management is incentivised to sell or it is forced to sell. While the latter may be achieved through a host of supervisory tools attached to the bank recovery and resolution plans and stress tests, as well as BRRD’s early intervention regime, a less enforced approach may secure higher market prices. On the other hand, unsurprisingly, especially where the deterioration of the loan book is mostly due to macroeconomic factors, shareholders (who presumably will resent being wiped out) and management (who presumably will be replaced) will obviously be less than happy to cooperate willingly. Of course, BRRD’s early intervention regime and some other provisions of EU regulatory regime offer wide supervisory discretion, up to and including changing management, with a view of replacing it with one presumably more energetic in tackling NPLs. But without resolving the underlying problems the supervisor must also be determined to push the bank into resolution. This of course entails (under the BRRD) a bail-in possibly in more than one bank, a feared prospect for regulators due to the capacity for systemic disruption when NPLs are spread system-wide, or anticipated problems to fund the bank post-resolution.

Bank management can be incentivised to sell if the price is closer to net book value, book value ex provisions, rather than the normally much lower market price, a gap that may in fact worsen in the case of forced selling leading to firesales. Profit and loss (P&L) agreements can resolve the issue of the final division of losses but they will not constitute a clean break for the bank’s balance sheet. Any future losses resulting from P&L arrangements act as a contingent liability inhibiting balance sheet growth for some time. Our earlier proposal considered capped P&L agreements to tackle this matter directly and avoid creating unlimited contingent liabilities. Another approach would be to make the banks hold an equity stake in the member state AMCs which would also help to increase the cushion that would be available before private bondholders are hit, allowing the banks to avoid facing extensive clawbacks. Nonetheless, bundling all banks in the same bracket regardless of their volume of NPLs and portfolio riskiness (objectively measured by reference to the recovery rate of NPLs) would raise moral hazard concerns.

3. The Proposal

3.1 AMC Rationale

In the absence of willing buyers at prices that would not be very far from banks’ estimations of the asset’s value, all recommendations for quick liquidation of NPLs in the current environment of low bank profitability would just deliver European banks straight into the hands of the resolution authorities, or worse into liquidation, despite the rapid modernisation of NPL tackling procedures through amendments to insolvency law and the adoption of requisite codes of conduct. We believe that this gap between expectations for rapid NPL resolution in the EZ and reality can be bridged through a specially designed AMC scheme.

AMCs, in general, have an encouraging record in tackling NPLs, notwithstanding the distributional concerns associated with the problem of valuations. Given the high level of corporate NPLs in the EBU and specialized turnaround (and possibly private equity) skills required to work-out such credits, AMCs also offer the distinct advantage of offering economies of scale in tackling corporate NPLs and creating liquid secondary markets for distressed debt. Yet only four countries use them in the EU (Ireland, Spain, Germany, and lately Italy). Moreover, a pan-European bad bank could ensure diversification of losses and peer pressure for the rapid resolution of NPLs. At the same time, we acknowledge that the “market for lemons” problem is asymmetrical from country to country and legislative reform is not sufficient to resolve it. In addition, costs of recovery can be uneven on a country by country basis, preventing the formation of a fully-fledged Pan-European bad bank. We also accept that, objections based on burden-sharing arguments are not going to go away, whatever the legal argument against them, as they are essentially part of the predominant (and unwritten) doctrine underpinning the EMU so far, i.e., that the fallen pay the price for their fall.

So, the circumstances call for an effective compromise solution. To this effect, we suggest that the following ideas can provide the best solution to the EBU bad-bank conundrum.

3.2 AMC Structure

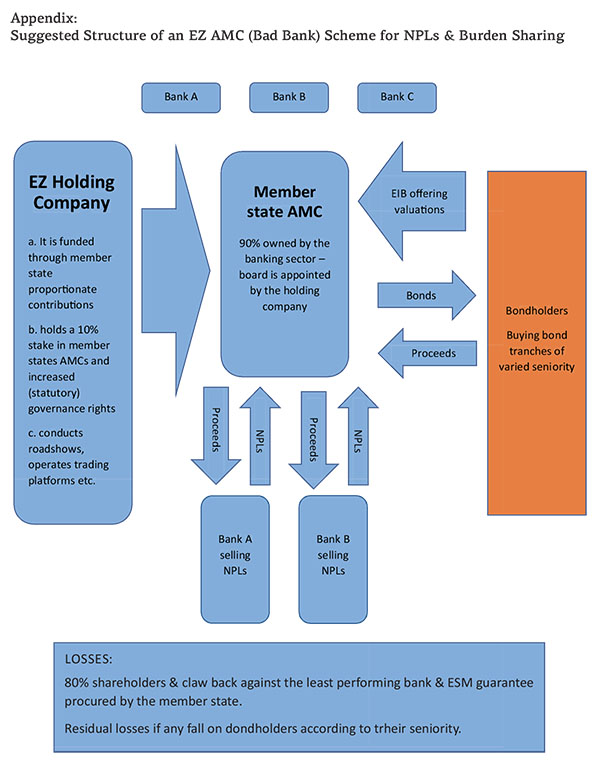

In our opinion the most effective approach to tackle NPLs through an AMC scheme would involve the formation of a pan-European holding company that would preside over quasi-ring-fenced country-based AMCs. The holding company would have as initial shareholders all EBU member states with a share-capital participation that would be a factor of a symbolic, but not totally insignificant, participation of (say 1 billion EUR) multiplied by the share of NPLs to total loans of the country’s banking sector multiplied by a factor that represents the country’s share of the EBU GDP. E.g., if we assume that Greece represents 2% of the EBU GDP and its level of NPLs is 45%, the Greek participation should be 1billion EUR x 45/50 = 900 million EUR. On the other hand, if we assume that Germany represents 40% of EBU GDP and its level of NPLs as certified by the competent supervisor, probably the single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) is 5%, the participation of Germany in the pan-European holding AMC would be 1billion EUR x 5/2.5= 2billion EUR. The holding company would set up country-based AMCs as subsidiaries. The initial shareholders of country AMCs would be the Holding Company participating as a private investor (but with increased governance rights) at a minimum of 10% of member state AMCs’ issued share capital. Namely, it would participate in the same way as, by analogy, a private equity limited partner with its potential losses firmly capped. The Holding Company’s participation to the member state AMCs would represent, at a minimum, the country’s participation in the holding company). All member state banks wishing to do business with the AMC would participate to the AMC’s initial share capital with a share-capital contribution (each) of a minimum x 1 times the country’s participation in the holding company, less if their share of NPLs over total loans is lower than the national average, more if their share is higher than the national average. The losses or profits of each AMC would be cleared at the national level. The board of the holding company would have the responsibility for appointing the board of country AMCs, holding an open tender. The three supervising institutions (SSM, the Commission, and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) would have to be informed of requisite appointments). Country AMCs would have to appoint the European Investment Bank (EIB) as an advisor to implement the valuation method advised below.

To avoid excessive upfront recapitalisations as well as unmanageable long-term losses to the AMCs and thus offer incentives to both bank management to sell the NPLs and private investors to buy debt issued by the AMCs, we suggest the following valuation approach. The NPLs would be transferred to the AMC at a price that is the weighted average (33% each) of the net book value (i.e., book value ex provisions), the long-term economic value of the asset as calculated by the EIB (LTEV),[3]The LTEV variable suggested here is already employed in the valuation of NPLs transferred by Irish banks to the country’s AMC the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA), which was set up in the … Continue reading and the market value of the assets to be transferred. The triple weighting is of course bound to provide a marked uplift in terms of transfer price. But it also reflects the fact that in some cases, e.g., Italy, the economy has posted anaemic growth rates since 2008 and before, so any economic boost would result in a substantial rise in market prices. Other countries, like Greece, Cyprus, Portugal, have lost a considerable portion of their GDP and any return to growth is bound to lift asset prices and thus valuations to substantially higher levels than current market prices.

One objective way to find the current market value could be through holding an auction under which the bank will sell to interested buyers a sample of assets similar to the assets about to be transferred to the AMC. Namely, the bids for the pre-transfer auctions would refer to actual transfers and not submission of fictitious bids, as was the case with Libor rate setting in the pre-2012 period. The fact that LTEV valuations would be conducted by the EIB could secure objectivity in the calculation of this key stabilising variable.

Overall the objective of the AMC would be to buy the asset at a price that wouldn’t trigger a requirement for extensive capital injections, so that, if possible, the impact on bank capital of relevant losses would be manageable, or could be amortized and absorbed in conjunction with other measures currently adopted to boost EU bank capital.

3.3 Burden-Loss-sharing

Following the winding up of the AMC operations any residual losses to the AMC would first be absorbed by its shareholders (i.e., the banks and the Pan-European AMC). The AMC could employ structured P&L agreements with banks. These agreements could provide the following claw back clause. When the losses from NPLS sold by a specific bank (or banks) exceed the average level of losses the AMC has experienced in its overall NPL portfolio, then that bank (banks) would have to make further payments to the AMC, amortized over a period and capped by the amount that the money loss emanating from the specific bank’s NPLs proportionately exceeded the amount the AMC would have lost if the specific bank’s (banks’) NPLs had scored the same levels of recovery as the portfolio average. This is a good way to penalize a bank (or banks) whose portfolio of transferred NPLs fall below AMC average in terms of recovery values. Such structured P&L arrangements would contain the worst offenders and thus they would counter moral hazard. In addition, they would maximize banks’ incentives to engage in honest conduct with the AMC.

80% of any further residual losses in the country-based scheme would be covered by an ESM guarantee that the country could procure at any time under the indirect bank recapitalization instrument (broadly defined, i.e., loans certainly include contingent future loans: guarantees) and under the so-called “precautionary recapitalisation” process, i.e., without triggering the BRRD conditions. The indirect “precautionary” recapitalisation facility is explicitly envisaged under the current ESM regulations. These arrangements would leave AMC’s private bondholders with very limited exposure to

AMC losses, thus, they significantly boost AMC’s chances to find private bond finance to fund its purchase of bank NPLs.

However, philosophical problems relating to moral hazard and the Too-Big-To-Fail concerns would remain. Thus, we suggest that banks selling NPLs to the AMC – other distressed financial instruments ought to be excluded from the scheme – could be subject to a structural conditionality to cede business and branches, if the authorities thought it necessary. Such conditionality would tackle fears of reinforcing big banks and the TBTF subsidy though the AMC scheme. It could also be a sufficient measure to conform with the EU state aid framework and open-up Eurozone banking markets to new contestants/entrants.

3.4 The distribution of competences between the Pan-European Holding Company and member state AMCs

The Holding Company should be a fund jointly owned by the participating member states set up to run for an initial period of five years. There is no reason for it to be an inter-governmental or EU agency. While it would seem logical that the Holding Company should be an ESM subsidiary, such a move might trigger fears of debt mutualisation. In addition, the ESM may have a conflict of interests given that it would provide guarantees to each member state-based AMC through the member state concerned. Thus, the holding company would have to be a separate corporate body that is wholly owned by the participating EZ member states.

The board of the Holding Company would report to the SSM, the EU Commission, and the ESM every 6 months. The reports could be made public. Each member state would be able to exercise the percentage of voting rights that would correspond to its stake in the Holding Company’s share capital.

In the beginning, the Holding Company would not be able to borrow money to downstream liquidity to its country subsidiaries but that restriction could be altered by a decision of the 2/3 of Holding Company shareholders. Voting in this case would be based on the principle of one share one vote. In the case that the board of the holding company cannot reach a decision on one of the matters it considers (other than leveraging its balance sheet), its articles should provide that in that case all shareholders’ voting rights are automatically transferred to the EU Commission, the ESM, and the ECB whose decisions would have to be taken by a two thirds majority of their own votes bypassing the company’s shareholders. This power should exist to discourage standstills and encourage consensus building.

Each country-based AMC would have the freedom to decide how to meet its financing needs given that this would also be dictated by the quality of its portfolio of assets. The funding strategy would be determined through a resolution of the AMCs’ shareholders in a process where the vote would be by majority and the holding company would not enjoy supra-voting rights, as in the case of board appointments. On the other hand, the holding company would ensure that each country-level (ring-fenced) subsidiary operates under the same conditions of governance, transparency, disclosure, and valuations. In addition, the holding company could establish and control FinTech platforms, given their ability to safely hold and disseminate due diligence reports, to effect direct sales of assets from the AMCs to any interested investors, augmenting the integrity and reliability of the platform.

Such centralisation of rules and operations presents distinct advantages. First, it secures comparability of operations and performance. Comparability of performance would of course expose NPL recovery problems generated by any odd legal and regulatory regimes. It would also eliminate any excuses on behalf of national authorities and bank management to create a functional secondary market for NPLs. Secondly, it would ameliorate governance and transparency discrepancies, since the matter of valuations would be handled by the EIB, and the AMC’s management would be a matter for the Pan-European AMC to decide and not of country authorities and bank AMC shareholders. In case of strong disagreements with the latter the three supervising institutions (the SSM, the Commission, and the ESM) could have the final word. Third, centralisation would augment the accountability of the management of AMCs. Fourth, the combined impact of centralisation of decision-making process and operations would take the sting of moral hazard and unequal governance away from the provision of an ESM guarantee to the country-based AMCs.

3.5 Legal Considerations

AMC transactions with going concern banks need not meet the BRRD requirements. NPLs could be transferred to the AMC by banks that have neither entered the resolution or pre-resolution stage. But another obstacle would remain: the EU state-aid rules under article 107 TFEU. Inevitably, such injection of public funds would indeed amount to some form of state assistance but could be allowed under certain circumstances under Article 107(3)(b) of the TFEU. In general, EU state aid rules have been applied to the EU banking sector with various degrees of flexibility. The suggested here ESM guarantee is not a permanent transfer and of course, it may never be triggered. If the ESM guarantee is offered (via the state) to the country AMCs on commercial terms, earlier decisions of the EU Commission on state aid by means of guarantees offered by the state on commercial terms become relevant.[4]See EU Commission, Press Release, “State aid: Commission gives final approval to existing guarantee ceiling for German HSH Nordbank”, 3 May 2016. The rationale of earlier Commission decisions on … Continue reading

However, the 2013 Commission Communication on State Aid Rules in the banking sector declared that state aid to assist with a capital shortfall should be preceded by all possible measures to minimise the cost of remedying that shortfall, including burden-sharing by shareholders and subordinated creditors. Micossi et al. 2016 point out that the Communication is the exception in the Commission’s State Aid jurisprudence and, in any case, it should not be construed independently of the Treaty Principle of Proportionality. Moreover, the Banking Communication itself (para. 45) offers an ‘exception rule’ from burden-sharing, which can be derogated when implementing burden-sharing measures would endanger financial stability or could lead to disproportionate results.

But while Advocate General Wahl in the Kotnik case,[5]Opinion of Advocate General Wahl, case C-526/14, Tadej Kotnik and Others v Državni zbor Republike Slovenije, 18 February 2016. the 2013 Communication expressing the view that the only binding legal rule is Article 107 the Court of Justice laid down instead some guidance on how the Communication should be interpreted holding it as binding.[6]Court of Justice of the European Union, case C-526/14, Tadej Kotnik and Others v Državni zbor Republike Slovenije 19 July 2016. In specific, the Court held that[7]Ibid.:

The burden-sharing measures are designed to ensure that, prior to the grant of any State aid, the banks which show a capital shortfall take steps, with their investors, to reduce that shortfall, specifically by raising equity capital and obtaining a contribution from subordinated creditors since such measures are likely to limit the amount of the State aid granted.

Clearly, this requirement is met by obliging banks to become shareholders in the AMC with the clear risk that their participation may be written off to absorb losses. But authorities may deem that to meet the burden sharing requirement banks participating in the suggested scheme may conduct rights issues to increase their equity capital buffers while selling their NPLs to the AMCs.

On the other hand, things are less clear as regards the conversion/write off of subordinated creditors. On this issue the Court gave a rather ambivalent interpretation, which, on the one hand, explicitly acknowledged that it is legal and legitimate for member states to refrain from bailing-in subordinated creditors outside the BRRD framework, and, on the other, it states that all such cases will be examined ad hoc and such exemption may make a state injection of funds fall foul of the state aid prohibition.[8]The Court’s exact wording is as follows: ‘As regards measures for conversion or write-down of subordinated debt, the Court considers that a Member State is not compelled to impose on banks in … Continue reading In our view the Court’s ambivalent statement on the matter should be read in conjunction with para. 45 of the Commission Banking Communication about exceptional circumstances. This combined reading leads to the conclusion that exempting subordinated creditors from sharing the burden of any NPL losses under the scheme will not endanger the legality of the scheme.

Accordingly, we believe that the hybrid Euro-AMC scheme suggested here will not fall foul of EU State Aid rules. The scheme secures a substantial amount of burden sharing (the paramount requirement of the EU communication and of the Enria 2017 plan) and the magnitude of the disturbance and the impact of the continuous debt overhang on the economies of the Eurozone countries concerned is such as to warrant the suggested measures.

Finally, the nature of any transfers via the ESM under the “precautionary recapitalisation” scheme would within the spirit of Art. 125 TFEU as authoritatively interpreted by the Court of Justice of the EU in the Pringle case.[9]Thomas Pringle v Government of Ireland, Ireland and The Attorney General Judgment of the Court of 27 November 2012, CJEU Case C-370/12, esp. paras 136-137. Reiterated in the more recent Peter … Continue reading

4. Conclusion

Most Eurozone leaders regard Pan-European AMCs with suspicion as there is a general fear of their redistributive outcomes. So, to clean up bank balance sheets without pushing Eurozone banks into bail-in centred recapitalisations, necessitated by the present dearth of investor interest in EZ bank equity, we have considered the possibility of a hybrid Euro-AMC. The holding company approach we have suggested secures the capping and minimisation of any fiscal transfers while it lays down the groundwork for a future EBU fiscal backstop for the banking sector which to us seems both desirable and inevitable, as much as it is legal under the Pringle reading of Art. 125 TFEU. In addition, the use of AMCs would act as a catalyst for attracting new private entrants and boosting liquidity in the euro-market for distressed bank debt. Sales of NPLs to a member state AMCs would free up capital for new lending, relieving Eurozone periphery’s debt overhang. Moreover, radical balance sheet cleaning up and the near elimination of banks’ future exposure would be good news for the market and could encourage fresh injections of equity investment in the EZ banks concerned. A final benefit is that the suggested AMC scheme could, indirectly, relieve current pressure placed on the ECB in the context of sometimes controversial bank bond purchase programmes.

Aiyar, S., Bergthaler, W., Garrido, J.M., Ilyna, A., Jobst, A., Kang, K., Kovtun, D., Monaghan, D., and Moretti, M. (2015). A Strategy for Resolving Europe’s Problem Loans. IMF Discussion Note.

Akerloff, G. (1970). The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84, 488-500.

Arner, D.W., Avgouleas, E., and Gibson, E. (2017). Overstating Moral Hazard: Lessons from 20 Years of Banking Crises. WP HKU Law School. March.

Bruno, B, Lusignani, G., and M. Onado, M. (2017). A Securitisation Scheme for Resolving Europe’s Problem Loans. Mimeo.

Court of Justice of the European Union (2016). Case C-526/14, Tadej Kotnik and Others v Državni zbor Republike Slovenije. July.

Daniel, J, Garrido, J., and Moretti, M. (2016). Debt-Equity Conversions and NPL Securitization in China—Some Initial Considerations. 16/05 IMF Technical Note.

Enria, A (2017). European banks’ risks and recovery – a single market perspective, Presentation to the ESM, January.

EU Commission (2013). Communication from the Commission on the application of State aid rules to support measures in favour of banks in the context of the financial crisis (‘Banking Communication’). August.

European Parliament (2017. Briefing: Non-performing loans in the Banking Union: state of play. PE 602.072, April.

Fell, J., Grodzicki, M., Martin, R., and O’Brien, E. (2016). Annex B: Addressing Market Failures in the Resolution of Non-Performing Loans in the Euro Area. ECB, Financial Stability Review, November.

Haben, P., and Quagliarello, M. (2017). Why the EU Needs and Asset Management Company. Central Banking, March 1-7.

Micossi, S., Bruzzone, G., and Cassella, M. (2016). State aid, bail-in, and systemic financial stability in the EU. Voxeu.org, June.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Akerloff (1970). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For a very comprehensive exposition of this problem see Bruno, B, G. Lusignani, and M. Onado (2017). |

| ↑3 | The LTEV variable suggested here is already employed in the valuation of NPLs transferred by Irish banks to the country’s AMC the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA), which was set up in the wake of the country’s bailout by the Eurozone and ensuing re capitalisation of its banking system. It is derived as a combination of market value and an uplift of 0-25% to reflect the long-term economic value of the asset when conditions in the market and the financial system normalize and the reasonably expected future yield of the asset based on historical performance. The weighted average uplift has been 8.2%. NAMA has bought NPLs from the Irish banks at an average discount of 57% of face value. |

| ↑4 | See EU Commission, Press Release, “State aid: Commission gives final approval to existing guarantee ceiling for German HSH Nordbank”, 3 May 2016. The rationale of earlier Commission decisions on the supply of an asset protection guarantee to Nordbank by its majority shareholders, the Landen of Hamburg and Schleswig Holstein, centered on the fact that the guarantee was offered on commercial terms. The latest decision requires drastic asset disposals. While the decision refers to state aid offered before the implementation of the BRRD and it is probably not the right precedent, the commercial terms language may not be ignored. |

| ↑5 | Opinion of Advocate General Wahl, case C-526/14, Tadej Kotnik and Others v Državni zbor Republike Slovenije, 18 February 2016. |

| ↑6 | Court of Justice of the European Union, case C-526/14, Tadej Kotnik and Others v Državni zbor Republike Slovenije 19 July 2016. |

| ↑7 | Ibid. |

| ↑8 | The Court’s exact wording is as follows: ‘As regards measures for conversion or write-down of subordinated debt, the Court considers that a Member State is not compelled to impose on banks in distress, prior to the grant of any State aid, an obligation to convert subordinated debt into equity or to affect a write-down of the principal of that debt, or an obligation to ensure that that debt contributes fully to the absorption of losses. In such circumstances, it will not however be possible for the envisaged State aid to be regarded as having been limited to what is strictly necessary. The Member State, and the banks who are to be the recipients of the contemplated State aid, take the risk that there will be a decision by the Commission declaring that aid to be incompatible with the internal market. The Court adds however that measures for conversion or write-down of subordinated debt must not go beyond what is necessary to overcome the shortfall of the bank concerned.’ Ibid. |

| ↑9 | Thomas Pringle v Government of Ireland, Ireland and The Attorney General Judgment of the Court of 27 November 2012, CJEU Case C-370/12, esp. paras 136-137. Reiterated in the more recent Peter Gauweiler and Others v Deutscher Bundestag (CJEU, Case C-62/14), paras. 135-136. |