This section of the journal indicates a few and briefly commented references that a non-expert reader may want to cover to obtain a first informed and broad view of the theme discussed in the current issue. These references are meant to possibly provide an extensive, though not exhaustive, insight into the main issues of the debate. More detailed and specific references are available in each article published in the current issue.

Institutions

The realization of a European Banking Union accomplishes a twofold task: first of all, it is an essential step towards the completion of the European and Monetary Union Project, and then, it is the response to the disruption of the 2007-2008 financial crises. The Banking Union currently applies to all the 28 Member States, covering approximately 6000 banks. Also countries not belonging to the euro area may become members, although no non-euro area country has joined it yet.

The foundation of the Banking Union relies on the implementation of the Single Rulebook, which includes provisions for capital regulation, deposit protection, and for banks’ recovery and resolution.

To implement the Banking Union, three pillars are being gradually introduced: these are setting up a Single Supervision Mechanism (SSM), a Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM), and a European scheme for Deposit Insurance (EDIS). This Section will only focus on the establishment of the SSM throughout the Banking Union, in line with the main subject of this Issue. Further details on the Single Rulebook, as well as on the SRM and EDIS can be found on the European Commission website. Angeloni (2016) in this issue provides an overwhelming description of the foundations of the Banking Union, and specifically focuses on the implementation of the SSM.

The Single Supervision Mechanism

The SSM bestows the European Central Bank (ECB) as the central prudential supervisor, ultimately responsible of financial stability and supervision related tasks. Also, the ECB is directly in charge of monitoring the largest banks, whereas national institutions are responsible for the remaining ones.

This single supervision scheme was included in the proposal of the European Commission[1]Available at http://ec.europa.eu/finance/general-policy/docs/committees/reform/20120912-com-2012-511_en.pdf., which conferred specific tasks, in terms of financial stability and banking supervision, to the ECB, thus giving rise to the principle of a Single Supervisory Mechanism. According to this Scheme, officially implemented from January 2014, all the 6000 active banks in the euro area will operate within the supervisory framework defined by the SSM[2]Also banks outside the euro area can partially join the SSM, upon the ECB’s final approval.. Still, supervisory duties can be allocated to different authorities, depending on banks’ size and significance, as discussed later in this section.

The recital of Article 4.2.1[3]Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52012PC0511&from=EN of the 2012 Council Proposal states that the ECB “will be exclusively competent for key supervisory tasks which are indispensable to detect risks for banks’ viability and require them to take the necessary action”.

On March 2013, a political agreement was reached by the European Parliament and Council on the 2012 package. Later in 2013, the European Union formally set forth the creation of the SSM by approving these two regulations: Council Regulation (EU) No. 2014/2013, conferring specific powers and tasks to the ECB, and Regulation (EU) No. 1022/2013 of the European Parliament and Council, establishing a European Supervisory Authority. Article 4 of Council Regulation (EU) No. 1024/2013[4] describes in detail the final specific tasks conferred to the ECB. Among other tasks, the ECB will be in charge of authorizing credit institutions and verify their compliance with existing capital requirements and with provisions on leverage and liquidity. Also, ECB will be in charge of undertaking early intervention measures if banks fail to comply with the above mentioned requirements. Recently, as further described later in this section, a draft regulation, together with a draft guideline for ECB, have undergone a public consultation process.

Although national supervisors will no longer be in charge of financial stability related tasks, they will be assigned with specific and residual tasks that are not contained in the list of tasks to be carried out by the ECB. Also, these national supervisors will perform an integral part of SSM activities by, for instance, preparing and implementing ECB acts, assessing the compliance of new banks’ requests, assisting banks from third countries in the establishment of a foreign branch or subsidiary, and so on.

Despite this task allocation, the Article 6 of the Council Regulation (EU) 1024/2013, on “Cooperation within the SSM”, lays out specific guidelines for implementing cooperation between central and peripheral supervisors. Among others, this article distinguishes between two different sets of banks. Larger and more significant banks, depending on their size, role in the economy, and cross-border activities, will be in fact under the direct supervision of ECB. Less significant institutions will be instead under the supervision of the National Competent Authorities (NCAs). As reported by Angeloni (2016) in this issue, under this single mechanism with a dual direct mandate, 122 banking groups, accounting from 80% of euro banks’ assets, are directly supervised by the ECB. The remaining 3500 banks are instead subjected to NCAs.

The establishment of a single supervisory body will also change the way cooperation occurs between home and host banks’ supervisors. More specifically, banks from the outside the euro area will be subject to both the ECB supervision, acting as a host authority, and the home regulator supervision. Hence, the ECB will have to closely cooperate with foreign national supervisors. To this purpose, Regulation 1024/2013 claims that the ECB and the competent authorities of other Member States shall agree upon a memorandum that includes cooperation guidelines.[4]More specifically, the introductory comment (14) on page 2 claims that “The ECB and the competent authorities of Member States that are not participating Member States (‘non-participating Member … Continue reading As for euro area banks instead, the ECB will act as both the home and host supervisor.

As for the options and discretion that can be exercised by the ECB, the impact assessment carried out by the Supervisory Board, as stressed by Angeloni (2016) in this issue, originated two new legal instruments, which were subject to a public consultation in November 2015. The first, legally binding instrument is a Public Consultation on a draft regulation of the European Central Bank on the exercise of options and discretions available in Union law[5]Available at https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/legalframework/publiccons/pdf/reporting/pub_con_draft_regulation_options_discretions.en.pdf?c1addc53eb2856b5805b1e75a6adb3af, that defines the leading principles for those significant credit institutions under the direct supervision of the ECB in terms of own funds, capital requirements, large exposures, and liquidity provisions. The second instrument is a Public Consultation on a draft ECB Guide on options and discretions available in Union law[6]Available at https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/legalframework/publiccons/pdf/reporting/pub_con_options_discretions_guide.en.pdf?f21cdb7b53b7fa1265e88c4643d09c10, setting out the guidelines for ECB in its exercising the options and discretions, when performing the supervisory tasks within the SSM, as set forth in Regulation (EU) 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council1 (CRR) and in Directive 2013/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council (CRD IV). In this way, this guide aims at ensuring a coherent, effective, and transparent approach as well as at assisting the Joint Supervisory Team in assessing individual requests and/or decisions that involve the exercise of option/discretion. More specifically, these guidelines refer to the application of CRR and CRD IV Regulation, thus providing best practices and standards for the evaluation of, among others, own funds, capital requirements, large exposures related issues. As stressed by Angeloni (2016) in this issue, both these instruments are expected to become fully enforced during spring 2016.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Available at http://ec.europa.eu/finance/general-policy/docs/committees/reform/20120912-com-2012-511_en.pdf. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Also banks outside the euro area can partially join the SSM, upon the ECB’s final approval. |

| ↑3 | Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52012PC0511&from=EN |

| ↑4 | More specifically, the introductory comment (14) on page 2 claims that “The ECB and the competent authorities of Member States that are not participating Member States (‘non-participating Member States’) should conclude a memorandum of understanding describing in general terms how they will cooperate with one another in the performance of their supervisory tasks under Union law in relation to the financial institutions referred to in this Regulation. The memorandum of understanding could, inter alia, clarify the consultation relating to decisions of the ECB having effect on subsidiaries or branches established in the nonparticipating. Member State whose parent undertaking is established in a participating Member State, and the cooperation in emergency situations, including early warning mechanisms in accordance with the procedures set out in relevant Union law. The memorandum should be reviewed on a regular basis.” |

| ↑5 | Available at https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/legalframework/publiccons/pdf/reporting/pub_con_draft_regulation_options_discretions.en.pdf?c1addc53eb2856b5805b1e75a6adb3af |

| ↑6 | Available at https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/legalframework/publiccons/pdf/reporting/pub_con_options_discretions_guide.en.pdf?f21cdb7b53b7fa1265e88c4643d09c10 |

Numbers

Multinational Banking

Figure 1

Source: ECB, Structural Financial Indicators. Total branches in destination countries are defined as the sum of branches of domestic banks, branches of banks from other EU member states, and branches of banks from all areas other than the EU.

Figure 2

Source: ECB, Structural Financial Indicators. Total foreign branches in destination countries are defined as the sum of branches of banks from other EU member states and branches of banks from all areas other than the EU.

Figure 3

Source: ECB, Structural Financial Indicators.

Figure 4

Source: ECB, Structural Financial Indicators and MFI Balance Sheet. Ratio between total assets of branches from other Euro Area countries and total assets of MFIs in destination countries.

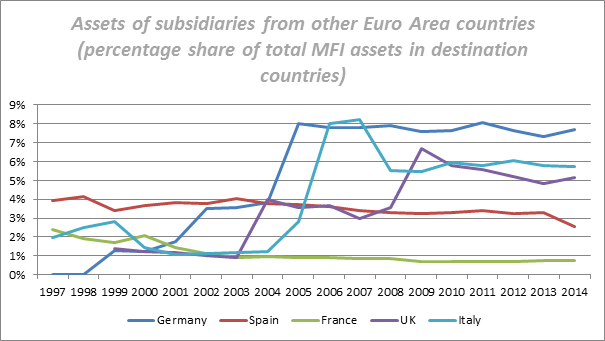

Figure 5

Source: ECB, Structural Financial Indicators and MFI Balance Sheet. Ratio between total assets of subsidiaries from other Euro Area countries and total assets of MFIs in destination countries.

Cross-border banking

Figure 6

Source: ECB, Balance Sheet Item. Loans (end of period, outstanding amount) by national MFIs vis-à-vis MFIs resident in the Euro Area (changing composition) as a share of total loans of national MFIs in originating countries.

Figure 7

Source: ECB, Balance Sheet Item. Loans (end of period, outstanding amount) by national MFIs vis-à-vis non-MFIs resident in the Euro Area (changing composition) as a share of total loans of national MFIs in originating countries.

Figure 8

Source: ECB, Balance Sheet Item. Deposit liabilities (end of period, outstanding amount) to national MFIs from MFIs resident in the Euro Area (changing composition) as a share of total deposit liabilities received by national MFIs in destination countries.

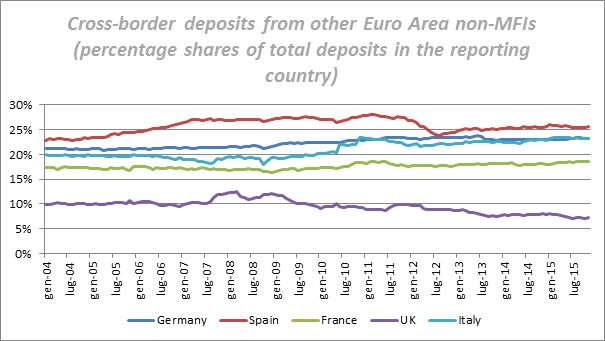

Figure 9

Source: ECB, Balance Sheet Item. Deposit liabilities (end of period, outstanding amount) to national MFIs from non-MFIs resident in the Euro Area (changing composition) as a share of total deposit liabilities received by national MFIs in destination countries.

A Bird Eye (Re)View of Key Readings

This section of the journal indicates a few and briefly commented references that a nonexpert reader may want to cover to obtain a first informed and broad view of the theme discussed in the current issue. These references are meant to possibly provide an extensive, though not exhaustive, insight into the main issues of the debate. More detailed and specific references are available in each article published in the current issue.

Institutions

To provide SMEs with an adequate credit flow and access to finance, especially during the recent economic crises, European and national legislators intervened in different ways, with direct financing measures, (public or private) credit guarantees, fostering securitisation of SMEs loans, and adjustments on capital requirements related to SMEs loans.