This journal section indicates a few and briefly commented references that a non-expert reader may want to cover to obtain a first informed and broad view of the theme discussed in the current issue. These references are meant to provide an extensive, though not exhaustive, insight into the main topics of the debate. More detailed and specific references are available in each article published in the current issue.

On the relevance of climate change risks

Understanding the effects of climate change on the financial system has emerged as one of the forefront issues globally (Hong et al., 2019, 2020). Climate change is believed to increase the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, raise average temperatures, and rising sea levels. Importantly, climate change already impacts economic and financial outcomes, which might have negative repercussions on financial systems. Correlated risks from climate change shocks could have effects beyond individual banks and borrowers to the broader financial system and economy. In this regard, in the pricing of residential mortgages does not incorporate climate change risks, a sudden correction could result in large-scale losses to banks, leading to reduced lending supply and jeopardizing financial stability. The subsequent declines in wealth could amplify the effects of climate change on the real economy, thus producing knock-on effects on financial markets (Nguyen et al., 2021).

Financial institutions must assess their vulnerabilities to relevant climate risks, as well as risks’ likely persistent and breadth, to be able to continue meeting the financial needs of households and companies when hit by disruptions caused by climate change. Remarkably, considering climate risks is relevant from the regulatory point of view. In this vein, the Federal Reserve created a dedicated supervision climate committee to observe the risks of climate change to individual banks. Likewise, the Bank of England expects its banks to understand and assess the financial risks related to climate change (Nguyen et al., 2021).

The recent studies are focused on exploring the ex-post effects of acute hazards, e.g., storms, floods, wildfires, on banks. In this regard, North and Schüwer (2018) show that natural disasters weaken financial stability. Similarly, Issler et al. (2020) find an augment in mortgage delinquency and foreclosure after wildfires. Ouazad and Kahn (2021) find that lenders are more likely to approve mortgages that can be securitized after hurricanes. Unlike acute hazards, the chronic ones -e.g., slow increases in sea levels- introduce the possibility that losses may arise from natural disasters. Despite the risk of chronic hazards causing losses, economists still know little about how such risks are priced ex-ante by banks. Consequently, more research is needed to understand how climate risk can be priced -ante by financial institutions, particularly the pricing of loans.

Interestingly, banks may not be able to price long-term climate change risks. The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2020a, b) estates that banks’ models still lack the necessary geographic precision or horizons to price climate risks. Another challenge can be uncertainty regarding the time horizon over climate risk can be materialized (Barnett et al., 2020). Furthermore, many banks still rely on traditional backward-looking models based on historical exposures, which might not adequately reflect climate risks’ complex and continuous changing nature. Moreover, considering the set of risks that banks are currently facing -e.g., cybersecurity, geopolitical risks, and risks associated with the credit cycle-along with the relative long-term horizon around climate change and risk (Nyberg and Wright, 2015). For instance, sea levels rise is a non-conventional risk and therefore, lenders pay equal attention to this risk or incorporate it into their pricing loan decisions (Jiang et al., 2020).

On carbon pricing and its repercussions on lending

Research on carbon risk is still embryonic. Stranded assets are physical assets whose value declines substantially due to climate risk. The carbon reduction requirements in the Paris Agreement and the policies oriented to fossil fuel firms might not be able to fully utilize their existing fossil fuel reserves (McGlade and Ekins, 2015), leading to a decline in the financial values of such reserves. The carbon risk from stranded assets in the fossil fuel industry can be priced, which constitutes an approach for assessing climate-related financial risks. However, carbon risk goes beyond stranded assets. Firms issuing large volumes of carbon are relatively more likely to suffer financial penalties if environmental policies tighten. Direct penalties can result from additional costs of carbon taxes on firms’ emissions. These can apply to firms in all industries with a carbon footprint and are not limited to fossil fuels producers (Ehlers et al., 2021).

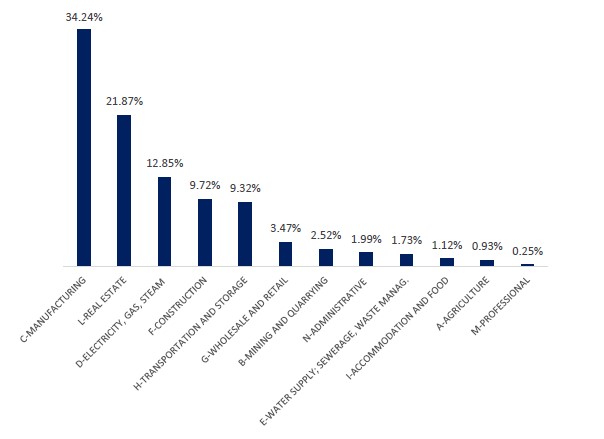

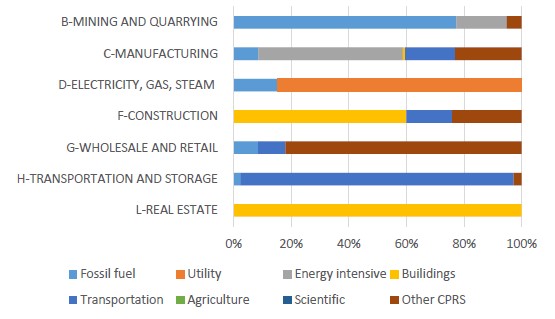

The pricing of carbon risk in the loan markets changed significantly after the Paris Agreement.[1]See the Institutions section in this issue. The difference in risk premia due to carbon emission intensity is apparently across industry sectors. Additionally, this phenomenon is broader than simply stranded assets in fossil fuel emissions or other carbon-intensive industries. Including loans fees and the premium is not prevalent in the years before the Paris Agreement, which increased banks’ awareness of carbon risk (Krueger et al., 2020). However, Delis et al. (2021) assess syndicated loan data for fossil fuel firms to investigate whether banks price the risk of stranded assets.[2]The corporate loan market, and specially the syndicated loans markets, constitutes an ideal laboratory to test hypotheses about the effects of climate change / risk on loan pricing, because banks … Continue reading They reveal that only after the 2015 Paris Agreement banks started pricing the risk of stranded assets related to fossil fuel reserves. Similarly, Kleimeier and Viehs (2018) also use syndicated loans data to investigate if forms voluntarily disclose their carbon emissions to the Carbon Disclosure Project, which allows them to reduce their cost of credit compared to non-disclosing firms. This result supportcs Antoniou et al. (2020), who theoretically find that loans spreads for firms participating in cap-and-trade programs function the cost of compliance and the specific features of the permits markets. Using the EU Emission Trading System, which is designed to pass the cost of CO2 emissions to polluters, this study suggests that the higher permits storage and lower permit prices, the lower firm financing costs.

Importantly, banks have started to internalize possible risks from the transition to a low-carbon economy across various industries. Krueger et al. (2020) suggest that carbon emissions indirectly caused by production inputs were not priced at the margin, suggesting that the overall carbon footprint is less of a concern to banks those direct missions. Likewise, Bolton and Kacperczyk (2021) find that the likelihood of disinvestment by institutional investors significantly augments with the degree and intensity of emissions directly attributable to firms. This suggests potential for ‘green-washing’ since the aforementioned emissions mentioned above can be reduced simply by outsourcing carbon-intensive activities withoutlowering the firm’s carbon footprint (Ben-David et al., 2018).

On the impact of climate change on equity markets

So far, research on the pricing of climate change risk, including carbon risk, has focused on the pricing of climate-related risks in equity markets. Recently, economists indicated that a transition risk premium in equity and option markets, which seems to be more pronounced in times of high climate change awareness. Mainly, the price of protection of option securities against the downside tail risk is higher for carbon-intense firms. In this regard, Bolton and Kacperczyk (2021) identify a carbon premium in the cross-section of the US stock market over the last decade. Particularly, the 2016 US climate policy shocks (the Trump election who appointed Scott Pruit, a climate sceptic, as administrator of the US Environmental Protection Agency) provide additional evidence that firms’ exposure impacts on their stock market valuation (Ramelli et al., 2021). Consequently, the valuation of carbon-intense firms rose. Goergen et al., (2020) assess carbon risk measures based on the firm’s overall strategy and its operational exposure to transition risk, including carbon emissions. Although they find that carbon risk is a priced risk factor, it does not find any evidence for a carbon premium in the global equity market.

On the capacity of banks to boost the climate change

As major providers of credit, banks are the key players in the effort to transition from a brown to a green economy. The momentum established by the COP21 enlarges the set of investment opportunities to finance green projects and renewable energy. Indeed, investment in the green economy has recently increased and is expected to grow enormously in market share (IEA, 2015; International Renewable Energy Agency, 2016). This increase is motivated by a growing consensus that supports movements towards a low-carbon economy and technological improvements that will lead to cost reductions in renewable energy, making alternatives to fossil fuel more appealing (Mazzucati and Perez, 2015; Krueger et al., 2015).

This might raise the question of how climate risks might directly impact financial institutions. Importantly, banks take on new risks in this regard, particularly physical and transition risks. On the one hand, physical risks arise from weather and climate-related disasters (Nordhaus, 1977; Stern, 2008; Nordhaus, 2019). These events can damage properties, reduce agricultural productivity, and impact deleteriously on human assets (Deryugina and Hsiang, 2014; O’Neil et al., 2017). Should this reduce the firms’ profitability and deteriorate their balance sheets, banks would be negatively affected in terms of asset values, collateral quality, and credit risk exposure. Furthermore, banks suffering large losses could diminish their lending availability, thus exacerbating the financial impact of physical risks by reducing credit supply. The blossoming literature provides theoretical and empirical evidence that banks should consider such physical risks in their investment decisions. Accordingly, Addoum et al. (2019) and Pankratz et al. (2019) show a negative correlation between firms exposed to extreme temperatures and profitability. Balvers et al. (2017) find that firms suffering from relatively high temperatures have higher cost of capital. This result connects with the literature advocating that extreme weather events are incorporated to stock and option markets (Dell et al., 2014; Kruttli etal., 2019; Choi et al., 2020).

On the other hand, banks should face transition risks that might arise from adjustments made toward developing a green economy. Particularly, transition risk depends on the timing and the speed of the process. Unanticipated changes in climate polices, regulations, technologies, and market sentiment could reprice the value of bank assets (CISL, 2019; Hong et al., 2019). Consequently, banks exposed to climate-sensitive sectors might be forced to fire carbon-intensive assets, leading to liquidity problems (Pereira da Silva, 2019). Therefore, this could create uncertainty and procyclicality and increase banks’ market risk (BoE, 2018). Transition risks could impact on bank credit risk if new technologies or changes in consumer behaviour towards “environmentally friendly” sectors lowered carbon-intensive firms’ profitability, further increasing their default risk (Krueger et al., 2020). Reghezza et al. (2021) analyse whether climate-oriented regulatory policies impact the flow of credit towards polluting corporations. Following the Paris Agreement, they find that European banks reallocated credit away from polluting companies. Consequently, green regulatory initiatives in banking can significantly impact on combating climate change.

Importantly, the COP21 is expected to impact the banking sector’s decisions. De Greiff et al. (2018) and Degryse et al. (2020a, b) assess the effect of climate risks on pricing in the syndicated loans. Since the COP21, banks have charged a premium for climate risk driven by increased awareness of climate policy-related risks. In particular, green firms have borrowed at comparatively lower prices since COP21 came into force.

Likewise, Delis et al. (2018) analysed the risk stemming from stranded fossil reserves, suggesting that, after 2015, banks started to price climate policy exposure by raising the cost of credit due to their awareness of transition risk. Ilhan et al. (2018), using a sample of high-emission industries in the S&P 500 before and after COP21, find that investors already incorporate information on climate-related risks when assessing risk profiles. Ginglinger and Moreau (2020) show that, after COP21, French companies subject to large climate risks reduced their leverage.

Regarding the financial system structure, De Haas and Popov (2019) find evidence of relatively lower CO2 emissions in more equity-funded economies, and they argue that stock markets contribute to reallocating investments toward less polluting industries. Similarly, Mesonnier (2019) investigates whether French banks reallocate credit from low intensive industries over the 2010-2017 period. They find that French banks reduce credit provision to more polluting industries.

References

Addoum, M. J., Ng, T. D. and Ortiz-Bobea, A. (2020). Temperature shocks and establishment sales. The Review of Financial Studies, 22: 1331-1336.

Antoniou, F., and Kyriakopoulou, E. (2019). On The Strategic Effect of International Permits Trading on Local Pollution. Environmental and Resource Economics, 74: 1299-1329.

Barnett, M., Brock, W., and Hansen, L. P. (2020). Pricing uncertainty induced by climate change. Review of Financial Studies, 33: 1024-1066.

Ben-David, I., Franzoni, F., and Moussawi, R. (2018). Do ETFs Increase Volatility? Journal of Finance, 73: 2471-2535.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2020a). Statement by Governor Lael Brainard. Available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/brainard-comment-20201109.htm (Accessed on February 2, 2022).

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System’s Financial Stability Report, November (2020b). See: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/financial-stability-report-20201109.pdf (Accessed on February 2, 2022).

BoE (2018). Transition in thinking: The impact of climate change on the UK banking sector. Bank of England Report, September 2018.

Bolton, P., and Kacperczyk, M.T. (2020). Do investors care about carbon risk? Journal of Financial Economics, 142: 517-549.

Choi, D., Gao, Z., and Jiang, W. (2020). Attention to global warming. The Review of Financial Studies, 33: 1112-1145.

CISL (2019). Unhedgeable risk: How climate change sentiment impacts investment. Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, Cambridge.

De Greiff, K., Ehlers, T. and Packer, F. (2018). The pricing and term structure of environmental risk in syndicated loans. Mimeo, Bank for International Settlements.

De Haas, R. and Popov, A. (2019). Finance and Carbon Emissions. ECB Working Paper Series, No 2318. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2318~44719344e8.en.pdf (Accessed on February 2, 2022).

Degryse, H., Goncharenko, R., Theunisz, C. and Vadasz, T. (2020). When green meets green. Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=16536

Degryse, H., Roukny, T. and Tielens, J. (2020), Banking barriers to the green economy. NBB Working Papers, No 391. Available at: https://www.nbb.be/en/articles/banking-barriers-green-economy (Accessed on February 2, 2022).

Delis, D. de Greiff, K., Iosifidi, M., and Ongena, S. (2021). Being Stranded with Fossil Fuel Reserves? Climate Policy Risk and the Pricing of Bank Loans. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper No. 18-10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3125017

Delis, M., De Greiff, K., and Ongena, S. (2018). Being stranded on the carbon bubble? Climate policy risk and the pricing of bank loans. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper Series, No 18-10, Swiss Finance Institute. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3125017

Dell, M., Jones, F. B., and Olken, B. (2014). What do we learn from the weather? The new climate-economy literature. Journal of Economic Perspective, 52: 740-798.

Deryugina, T., and Hsiang, M. S. (2014). Does the environment still matter? Daily temperature and income in the United States. NBER Working Papers, No 20750, National Bureau of Economic Research, December. DOI 10.3386/w20750

Ehlers, T., Packer, F., and Greiff, K. (2021). The pricing of carbon risk in syndicated loans: which risks are priced and why? BIS Working Papers No 946. Available at: https://www.bis.org/publ/work946.pdf (Accessed on February 2, 2022).

Ginglinger, D., and Moreau, Q. (2019). Climate risk and capital structure. Mimeo.

Goergen, M., Jacob, A., Nerlinger, M., Riordan, R., Rohleder, M., and Wilkens, M. (2020). Carbon risk. Working Paper. Available at: https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/events/2019/november/economics-of-climate-change/files/Paper-6-2019-11-8-Riordan-1PM-2nd-paper.pdf (Accessed on February 2, 2022).

Hong, H., Karolyi, G. A., and Scheinkman, J. A. (2020). Climate finance. Review of Financial Studies, 33: 1011-1023.

Hong, H., Li, F. W., and Xu, J. (2019). Climate risk and market efficiency. Journal of

Econometrics 208: 265-281.

International Energy Agency. (2015). World energy outlook 2014, Paris.

Ilhan, E. Z. S., and Vikov, G. (2018). Carbon tail risk. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Issler, P., Stanton, R., Vergara-Alert, C., and Wallace, N. (2020). Mortgage Markets with Climate-Change Risk: Evidence from Wildfires in California, Working paper. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3511843

Jiang, F., Li, C. W., and Qian, Y. (2020). Do costs of corporate loans rise with sea level? Working paper. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3477450

Kleimeier, S., and Viehs, M. (2018). Carbon Disclosure, Emission Levels, and the Cost of Debt. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2719665

Krueger, P., Sautner, Z., and Starks, L.T. (2020) The Importance of Climate Risks for Institutional Investors. The Review of Financial Studies, 33: 1067–1111.

Kruttli, S. M., Tran, R. B., and Watugala, W. S. (2019). Pricing Poseidon: Extreme weather uncertainty and firm return dynamics. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, No 2019-054, Board of the Federal Reserve System.

Mazzucato, M., and Perez, C. (2015). Innovation as growth policy. The Triple Challenge for Europe. In Fagerberg, J., Laestadius, S., and Martin, B.R.: 229-264. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198747413.001.0001

McGlade C, and Ekins P. (2015). The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2 °C. Nature. Jan 8;517(7533):187-90. DOI: 10.1038/nature14016. PMID: 25567285.

Mesonnier, J. S. (2019). Banks’ climate commitments and credit to brown industries: new evidence for France. Banque de France Working Papers, No 743, Paris, November. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3502681

Nguyen, D.D., Ongena, S., Qi, S., and Sila, V. (2021). Climate Change Risk and the Cost of Mortgage Credit. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper Series N°20-97. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3738234

Nordhaus, W. D. (1977). Economic growth and climate: The carbon-dioxide problem. American Economic Review, 67: 341-346.

Nordhaus, W. D. (2019). Climate change: The ultimate challenge for economics. American Economic Review, 109: 1991-2014.

Noth, F., and Schuwer, U. (2018). Natural disaster and bank stability: Evidence from the US financial system. SAFE Working Paper No. 167. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2921000

Nyberg, D., and Wright, C. (2015). Performative and political: Corporate constructions of climate change risk. Organization, 23: 617-638.

O’Neil, C. B., Kriegler, E., Ebi, L. K., Kemp-Benedict, E., Riahi, K., Rothman, S. D., Van Ruijven, J, B., Van Vuuren, D. P., Birkmann, J., Kok, K., Levy, M., and Solecki, W. (2017). The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Global Environmental Change, 42: 169-180.

Ouazad, A., and Kahn, M. E. (2021). Mortgage finance and climate change: Securitization dynamics in the aftermath of natural disasters. NBER working paper 26322. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w26322 (Accessed on February 2, 2022).

Pankratz, N. M. C., Bauer, R. and Derwall, J. (2019). Climate change, firm performance and investor surprises. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3443146

Pereira da Silva, L. (2019). Research on climate-related risks and financial stability: An epistemological break? Based on remarks at the Conference of the Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS).

Ramelli, S., Wagner, A.F., Zeckhauser, R.J., and Ziegler, A. (2021) Investor Rewards to Climate Responsibility: Stock-Price Responses to the Opposite Shocks of the 2016 and 2020 U.S. Elections. Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 10: 748-787.

Reghezza, A., Altunbas, Y., Marques-Ibañez, Rodriguez-d’Acri, C., Spaggiari, M. (2021). Do banks fuel climate change? ECB Working Paper Series, No 2550. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2550~24c25d5791.en.pdf (Accessed on February 2, 2022).

Stern, N. (2008). The economics of climate change. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 98: 1-37.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | See the Institutions section in this issue. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The corporate loan market, and specially the syndicated loans markets, constitutes an ideal laboratory to test hypotheses about the effects of climate change / risk on loan pricing, because banks that are the lead arrangers of syndicated loans are informed and incentivized to monitor, and data are widely available (Delis et al., 2021). |