Authors

Ralph De Haas[1]Ralph De Haas is the Director of Research at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and a part-time Professor of Finance at KU Leuven. He thanks Helena Schweiger, Rada Tomova, … Continue reading

1. Introduction

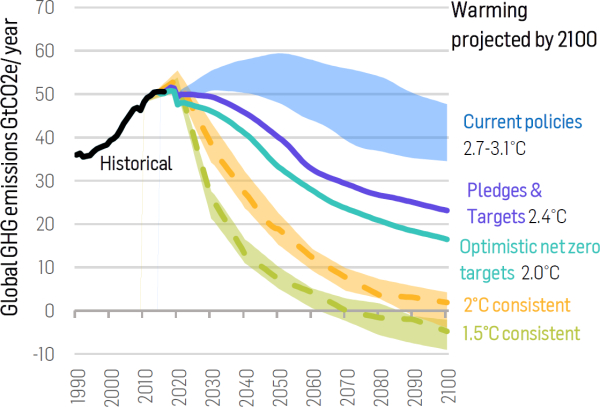

There now exists incontrovertible evidence that human activity, mainly in the form of carbon emissions from industrial production, is warming up the Earth at a rate that has been unprecedented for at least 2000 years (IPCC, 2021). The day-to-day impact of this global warming is becoming increasingly apparent. Extreme temperatures, droughts, floods, and storms are already causing substantial human, ecological, and economic losses.

In the absence of scalable technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the biosphere, mitigating climate change will require a drastic reduction of new carbon emissions. For this reason, and in line with the Paris Climate Agreement, many countries aim to produce zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 at the latest (Millar et al., 2017). This green transition (that is, the road to net zero) will require massive public, private, and public-private investment to develop and then implement cleaner technologies. For example, several governments are currently investing heavily in the development of better lithium-ion batteries and electrolysers to produce hydrogen. At the same time, some private enterprises are investing to make their production methods more energy efficient and to develop new, greener technologies from scratch.

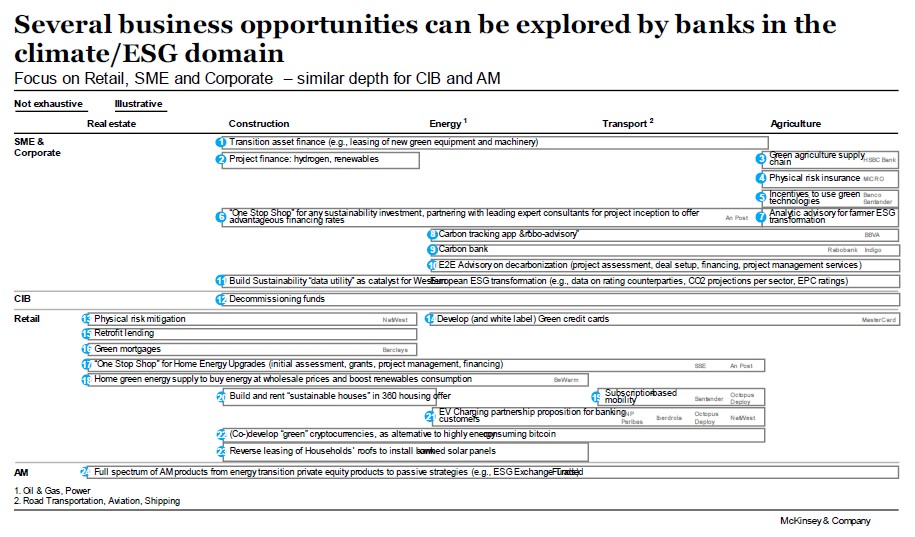

How can the financial system – banks, bonds, as well as public and private equity – facilitate this green transition? A well-established literature has by now shown convincingly that deeper financial systems can foster economic growth (Levine, 1997). An open question is whether the financial sector also influences the ‘greenness’ of economic growth? For example, large-scale investments to invent and then implement green technologies may only be possible if firms can access external finance. Moreover, some sources of finance may be better suited to fund green investment than others. The financial structure of a country may then co-determine how polluting its development path turns out to be.

This article discusses some emerging evidence on the nexus between the financial system, carbon emissions, and economic growth. I will make three main points. First, I will argue that bank credit can help firms to reduce toxic emissions and, to some extent, to improve the energy efficiency of their existing production processes. Second, I will also argue that other organisational constraints, in particular weak firm management, often hold back green investment more than credit constraints do. Third, I will claim that green innovation flourishes more where and when the financial sector is more equity-based and less bank-based.

2. Bank lending, toxic emissions, and investments in energy efficiency

Especially during the early stages of the green transition, substantial emission reductions can be achieved by making corporate production (as well as buildings) more energy efficient. In fact, energy efficiency measures could take care of more than 40 percent of the carbon abatement required by 2040 to remain in line with the Paris Agreement (IEA, 2018). This means large-scale industrial investment is needed in cleaner technologies to reduce firms’ carbon footprint. Unfortunately, many firms – especially smaller ones – not only lack internal funding to invest in energy efficiency measures, they often also cannot access bank credit to do so. When credit constraints bite, climate investments may suffer.

An emerging literature shows that when firms get better access to bank loans, the amount of toxic pollution they emit locally often falls. This is presumably because bank credit allows them to invest in, and hence clean up, their production processes. For example Levine, Lin, Wang, and Xi (2018) show how positive credit supply shocks in U.S. counties help to reduce local air pollution. Likewise, Götz (2019) finds that financially constrained firms reduced toxic emissions once their capital cost decreased as a result of the U.S. Maturity Extension Program. Xu and Kim (2022) also find that financial constraints increase firms’ toxic releases. Their evidence suggests that firms trade off pollution abatement costs against potential legal liabilities: the impact of financial constraints on toxic releases is stronger when regulatory enforcement is weaker.

To what extent does access to bank credit not only allow firms to reduce their emission of locally-polluting toxins but also of globally-harmful carbon? Carbon emissions are less visibly harmful at the local level and hence tend to expose firms to less legal risk. Firms may therefore deprioritize investments to reduce such emissions. Recent evidence confirms that while access to bank loans can help firms to limit carbon emissions, credit constraints appear not to be the most binding organizational constraint. For example, a cross-country survey of firm managers shows that despite the potential environmental and efficiency benefits of green investments, many firms refrain from implementing such measures (EBRD, 2019). Close to 60 percent of all interviewed firms see investments in energy efficiency as low priority relative to other investments. A lack of financial resources is the second-most cited reason not to do so, but this answer is only given by about 15 percent of all interviewed managers.

De Haas, Martin, Muûls, and Schweiger (2021) investigate these data in more detail and focus in particular on the relative important of credit constraints versus managerial constraints. They measure each firm’s green management practices by using standardized data on firms’ strategic objectives concerning the environment and climate change. This includes whether there is a manager with an explicit mandate to deal with environmental issues; and how the firm sets and monitors targets (if any) related to energy and water usage, carbon emissions, and other pollutants. In addition, they track which green investments firms made in the recent past. Green investments include machinery and vehicle upgrades; heating, cooling and lighting improvements; the on-site generation of green energy; waste minimization, recycling and waste management; improvements in energy and water management; and measures to control air or other pollution.

Their analysis shows how both credit constraints and green management influence the likelihood of green investments. Credit constraints hinder capital-intensive green investments in particular, such as machinery and vehicle upgrades and improved heating, cooling or lighting. They do not significantly reduce the likelihood of investing in air and other pollution control, potentially due to the “low-hanging fruit” nature of such investments. Firms with good green management practices, on the other hand, are more likely to invest in all types of green investment, with the effect larger for those more typically thought of as green: waste and recycling; energy or water management; air and other pollution controls.

If credit constraints and weak green management reduce firms’ green investments, then this may eventually also hamper decarbonisation efforts. To investigate this, the authors use the European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR) and focus on a sample of Eastern European countries. The E-PRTR contains data on pollutant emissions of a large number of industrial facilities. Their estimates indicate that, although there was a secular emission reduction during 2007-17, this decline was smaller in localities where banks had to deleverage more after the global financial crisis and where, as a result, more firms were credit constrained.

In sum, a growing body of evidence indicates that when firms have better access to bank credit, they may invest more in cleaner production technologies. This may not only reduce (local) toxic emissions but also (global) carbon emissions. At the same time, for many important energy-efficiency measures that firms can take, access to credit is less of a constraint than the quality of firms’ (green) management. Better-managed firms tend to produce more cleanly, and this is often unrelated to their ability to access bank credit.

3. Banks and green innovation

The previous section shows that banks can help, to some extent, with funding investment in tried-and-tested technologies that enhance firms’ energy efficiency. Yet, the steep emission decline needed to achieve net zero by 2050 also requires developing entirely new production technologies. There are at least three reasons to believe that banks may be less willing (or able) to finance R&D into such innovative, greener technologies.

First, many banks tend to be inherently technologically conservative. They fear that funding new (and possibly cleaner) technologies will erode the value of collateral that underpins their existing loans – and which firms used to finance older technologies (Minetti, 2011; Degryse, Roukny, and Tielens, 2020). Second, green innovation (as does any innovation) often involves assets that are intangible and highly firm-specific. Many banks would instead be more comfortable with funding tangible and easily collateralisable assets. Third, banks often have a shorter time horizon (the loan maturity) than equity investors and are hence less interested in whether assets will become less valuable (or even stranded) in the more distant future. For example, banks have only very recently started to price some of the climate risk related to firms with large fossil fuel reserves (Delis, De Greiff, and Ongena, 2018). Even then, many (large) banks continue to provide syndicated loans to fossil fuel firms at spreads that under-price the risk of stranded assets – as compared to bonds issued by those firms. As a result, carbon producers are gradually switching from bond to bank funding (Beyene, Delis, De Greiff, and Ongena, 2021).

4. Equity and green innovation

Stock markets may be better suited to fund innovative (and greener) technologies. By their nature, equity contracts are more appropriate to finance projects characterized by both high risks and high potential returns. To the extent that stock prices rationally discount future cash flows of polluting industries, equity investors may, in fact, be more sensitive to the costs and risks of pollution – even if these may only materialize in the future.

A key question is therefore to what extent equity investors take carbon emissions into account when assessing longer-term corporate risk. A growing body of evidence suggests that especially institutional investors are increasingly doing so. Survey evidence by Krueger, Sautner, and Starks (2020) shows that a large proportion of investment managers believe that climate risk is already affecting their portfolio companies. Almost 40 percent of the surveyed investors are therefore aiming to reduce the carbon footprint of their portfolios, including through active engagement with management[2]This not only holds for investors in developed markets but increasingly also for those investing in emerging market securities (EBRD, 2021).. Such investors may also benefit from pushing companies to reduce carbon emissions because this helps to attract environmentally responsible investment clients (Ceccarelli, Ramelli and Wagner, 2020). Because institutional investors are taking carbon emissions into account when assessing corporate risk, Bolton and Kacperczyk (2021) find that stocks of U.S. firms with higher carbon emissions earn higher returns. Moreover, investors appear to shun carbon-intensive companies, although this effect is limited to direct emissions from production and to the most carbon-intense industries. Recent evidence shows that also private equity providers can help to clean up production processes. Bellon (2020) find that private equity investors have helped to reduce pollution (both CO2 and toxic chemicals) in the oil and gas industry.

5. Reducing carbon emissions: Banks versus equity

The above discussion raises the question whether in the aggregate, countries with deeper stock markets relative to banking sectors may in fact follow steeper decarbonisation trajectories. To help answer this question, De Haas and Popov (2021) compare the role of banks and equity markets as potential financiers of green growth. Using a 48-country, 16-industry, 26-year panel data set, they assess the impact of both the size and the structure of the financial system on industries with different levels of carbon intensity. In particular, they distinguish industries on the basis of their inherent, technological propensity to pollute, measured as the carbon dioxide emissions per unit of value added. The authors then investigate two channels through which financial development and financial structure (the relative size of equity markets relative to banking sectors) can affect pollution: between-industry reallocation and within-industry innovation.

Using this empirical framework, the authors derive three findings. First, industries that pollute more for technological reasons, start to emit relatively less carbon dioxide where and when stock markets expand. Second, there are two distinct channels that underpin this result. Most importantly, stock markets facilitate the development of cleaner technologies within polluting industries. Using data on green patents, the authors show that deeper stock markets are associated with more green patenting in carbon-intensive industries. This patenting effect is strongest for inventions to increase the energy efficiency of industrial production. In line with this positive role of stock markets for green innovation, carbon emissions per unit of value added decline relatively more in carbon-intensive sectors when stock markets account for an increasing share of all corporate funding. There is also more tentative evidence for another channel: holding cross-industry differences in technology constant, stock markets appear to gradually reallocate investment towards more carbon-efficient sectors. This is in line with the aforementioned tendency of (some) institutional investors to avoid the most carbon-intensive sectors. Polluting firms in these sectors will then find it more difficult to access external finance, putting them at a competitive disadvantage compared with cleaner companies.

Third, the domestic green benefits of more developed stock markets ‘ at home’ may be offset by more pollution abroad, for instance because equity-funded firms offshore the most carbon-intensive parts of their production to foreign pollution havens. Analysis shows that the reduction in emissions by carbon-intensive sectors due to domestic stock market development is indeed accompanied by an increase in carbon embedded in imports of the same sector. However, the domestic greening effect dominates the pollution outsourcing effect by a factor of ten. This means that stock markets may have a genuine cleansing effect on polluting industries and do not simply help such industries to shift carbon-intensive activities to foreign pollution havens.

6. Conclusions

This introductory article has discussed some emerging evidence on the nexus between the financial system, carbon emissions, and economic growth. The evidence shows that while bank lending can help firms to improve the energy efficiency of their current production processes, other organisational constraints, in particular weak firm management, often hold back green investments more than credit constraints. While policy measures that ease access to bank credit may be useful (for example, credit lines that are contingent on the adoption of state-of-the-art energy efficiency technologies) this might just be one element of a broader policy mix to stimulate green investments to boost firms’ energy efficiency.

Governments and development banks may also consider measures to directly help strengthen firms’ green management practices. Advisory services, training programs, and other consultancy related firm-level interventions can help managers to become better “green managers”. Such interventions effectively teach managers how to not leave money at the table by postponing much-needed investments in energy efficiency.

Efforts to increase green investments by reducing credit constraints and by enhancing firms’ managerial skills, will only pay off when the broader institutional framework is supportive. This means in particular that highly distortionary fossil fuel subsidies need to be eradicated. Recent evidence reveals that better-managed firms tend to reduce the fossil-fuel intensity of their production unless they can exploit high fuel subsidies (Schweiger and Stepanov, 2022). Moreover, the introduction of carbon pricing – either through a carbon tax or through a cap-and-trade system – can incentivise firms to stop procrastinating and instead invest in measures to make their production more energy efficient. The role of the financial sector is then a complementary one: it mobilises the funding for investments in energy-efficiency improvements and new technologies as firms respond to prices signals coming from, for example, carbon taxes. It is up to politicians and policy makers to create a policy framework that sets the rights incentives for firms to transition to net zero. The role of the financial system to then help firms to achieve this transition in an efficient way.

A second lesson from recent research is that green innovation tends to flourish more where and when finance is more equity-based and less bank-based. Countries with a bank-based financial system that are on the transition path towards net zero carbon emissions, may therefore also consider measures to stimulate the development of conventional equity markets. This holds especially for middle-income countries where carbon dioxide emissions may have increased more or less linearly during the development process. There, stock markets could play an important role in making future growth greener, in particular by stimulating innovation that leads to cleaner production processes within industries.

One way of doing so, especially in smaller economies, is through the regional integration of smaller equity markets. Such integration could target cross-border market infrastructure (such as links between stock exchanges and securities depositories); the harmonization of regulations; as well as capital market accelerator funds with regional mandates. An example is the successful consolidation of national stock markets in the Baltic region. Nasdaq Baltic operates the stock exchanges in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, as well as a common Central Securities Depository. It provides capital market infrastructure across the whole value chain, including listing, trading, and market data, as well as post-trade services including clearing, settlement and safe-keeping of securities. This makes it easier for investors to transact cross-border and, ultimately, for firms to raise equity. Similar efforts are ongoing to integrate several stock exchanges in the Balkans.

Another way to help develop equity markets that can provide firms with the equity needed for green innovation, is by levelling the playing field between the cost of equity and the cost of debt. Countries that want to limit the negative environmental externalities stemming from a financial system that is overly reliant on bank lending (and debt more generally) can reduce tax-code favouritism towards debt (such as the deductibility of interest payments and double taxation of dividends). An example is the notional interest deduction that Belgium introduced in 2006. Similarly, as part of the European Commission’s work on the Capital Markets Union, a common corporate tax base has been proposed to address the current debt bias in corporate taxation. A so-called Allowance for Growth and Investment will give firms equivalent tax benefits for equity and debt.

In parallel, countries can take measures to counterbalance the tendency of banking sectors to (continue to) finance relatively “dirty” industries. Examples include the green credit guidelines and resolutions that China and Brazil introduced in 2012 and 2014, respectively, to encourage banks to improve their environmental and social performance and to lend more to firms that are part of the low-carbon economy. From an industry perspective, adherence to the so-called Carbon Principles, Climate Principles, Equator Principles, UN Principles for Responsible Banking, as well as the Collective Commitment to Climate Action should also contribute to a greening of bank lending. Strict adherence to these principles can potentially make governmental climate change policies more effective by accelerating capital reallocation and investment towards low-carbon technologies.

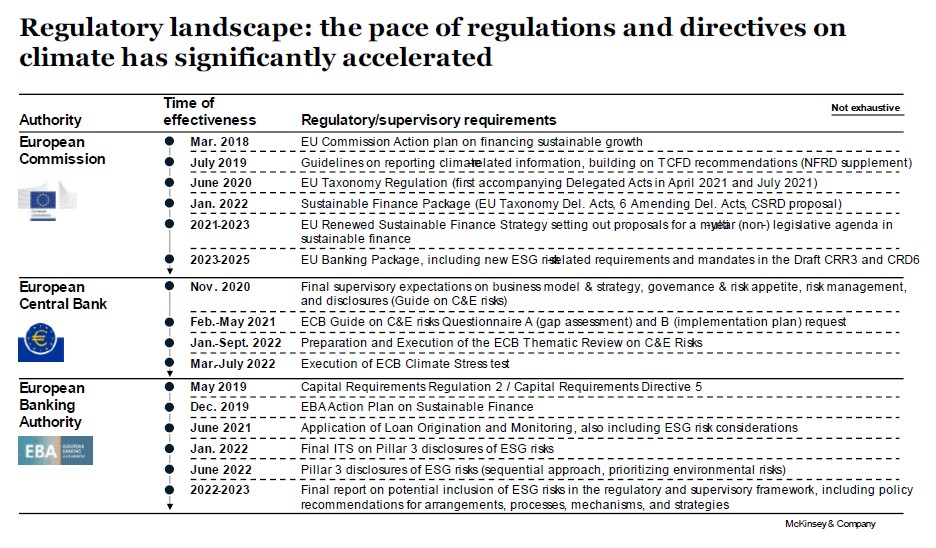

To incentivize and enable banks to adhere to these Principles in a meaningful way, supervisory climate stress tests, such as currently being undertaken by the European Central Bank, can be useful. Moreover, a growing number of banking supervisors – as part of developing a Pillar 3 framework on ESG risks and in line with the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures – is moving towards mandatory disclosure of climate-related financial risks. The meaningful disclosure of climate risks will allow depositors, investors, and other stakeholders to make more informed decisions and hence to enhance market discipline. Relatedly, the meaningful disclosure of climate risks by companies is a precondition for banks and other providers of capital to understand and manage climate-related risks. This work is likely to be facilitated by that of recently announced International Sustainability Standards Board, which aims to create a global, comparable set of sustainability standards.

Lastly, the so-called Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), a United Nations initiative, brings together banks that are committed to align their portfolios with net-zero emissions by 2050. A useful aspect of this alliance is that it helps banks to set (and publicly commit to) an intermediate target for 2030 or sooner, thereby accelerating their decarbonisation strategies and making them more credible. Even then, voluntary commitments may not suffice, as evidenced by the fact that many global banks that signed up to the NZBA and similar initiatives continue to finance fossil-fuel extraction at scale. Banks looking for more credible decarbonisation strategies may choose to have their strategies validated by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), an independent body that assesses whether banks strategies are aligned with the Paris goal of limiting global warming to 2° C.

References

Bellon, A. (2020). Does Private Equity Ownership Make Firms Cleaner? The Role of Environmental Liability Risks. Mimeo.

Bolton, P., and Kacperczyk, M.T. (2021). Do Investors Care about Carbon Risk? Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2): 517-549.

Ceccarelli, M., Ramelli, S., and Wagner, A. (2020). Low-Carbon Mutual Funds. mimeo.

Degryse, H., Roukny, T., and Tielens, J. (2020). Banking Barriers to the Green Economy. Working Paper 391, National Bank of Belgium, Brussels.

De Haas, R., Martin, R., Muûls, M., and Schweiger, H. (2021). Managerial and Financial Barriers to the Green Transition. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15886, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London.

De Haas, R., and Popov, A. (2021). Finance and Green Growth. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 14012, Center for Economic Policy Research, London.

Delis, M.D., de Greiff, K., and Ongena, S. (2018). Being Stranded on the Carbon Bubble? Climate Policy Risk and the Pricing of Bank Loans. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 12928.

EBRD (2019). Transition Report 2019-20: Better Governance, Better Economies. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, London.

EBRD (2021). The Investor Base of Securities Markets in the EBRD Regions, 3rd Edition, April, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, London.

IEA (2018). Energy Efficiency 2018. Analysis and Outlooks to 2040. International Energy Agency (IEA), Paris.

IPCC (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Cambridge University Press.

Götz, M. (2019). Financing Conditions and Toxic Emissions. SAFE Working Paper No. 254, Frankfurt.

Krueger, P., Sautner, Z., and Starks, L.T. (2020). The Importance of Climate Risks for Institutional Investors. Review of Financial Studies, 33(3): 1067-1111.

Levine, R. (1997). Financial Development and Economic Growth: Views and Agenda, Journal of Economic Literature, 35(2): 688-726.

Levine, R., Lin, C., Wang, Z., and Xie, W. (2018). Bank Liquidity, Credit Supply, and the Environment. NBER Discussion Paper No. 24375, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Millar, R.J., Fuglestvedt, J.S., and P. Friedlingstein et al. (2017). Emission Budgets and Pathways Consistent with Limiting Warming to 1.5°C. Nature Geosience, 10: 741-747.

Minetti, R. (2011). Informed Finance and Technological Conservatism. Review of Finance, 15(3): 633-692.

Schweiger, H., and Stepanov, A. (2022). When Good Managers Face Bad Incentives: Management Quality and Fuel Intensity in the Presence of Price Distortions. Energy Policy, forthcoming.

Xu, Q., and Kim, T. (2022). Financial Constraints and Corporate Environmental Policies. Review of Financial Studies, 35(2): 576-635.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Ralph De Haas is the Director of Research at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and a part-time Professor of Finance at KU Leuven. He thanks Helena Schweiger, Rada Tomova, and Ulrich Volz for useful comments. EBRD, KU Leuven, and CEPR. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This not only holds for investors in developed markets but increasingly also for those investing in emerging market securities (EBRD, 2021). |