Authors

Giorgio Barba Navaretti[1]University of Milan., Giacomo Calzolari[2]European University Institute. and Alberto Franco Pozzolo[3]Roma Tre University.

1. Introduction

Information is the main character in open banking (OB), which is about opening to third parties the access to information that is otherwise captive in a bilateral relationship between the incumbent provider of financial services and the client. With the words of Rivero and Vives in this issue, OB “refers to those actions that allow third-party firms, either regulated banks or non-bank entities, to have access under customer consent to their data through application programming interfaces (API)”.

Specifically, open banking aims at creating a market for customers’ transaction data, obtained (mostly although not only) from payment information. Traditionally, these data were accessible only by the financial intermediary performing the transaction and they were rather cumbersome to transfer. This gave banks the possibility to leverage on the data and extract higher rents from the interactions with their customers. OB allows customers to easily, swiftly and freely transfer their own payment information to any authorized third party of their choice, thus changing the conditions for transactions with their financial intermediaries.

Where does OB come from? The kick start comes from regulation. In the European Union, the starting point was the approval in 2015 of PSD2, the revision of the Payment Services Directive by the European Commission,[4]Directive (EU) 2015/2366, known as PSD2, see the Institutions section below. which requires that financial institutions open up they data in favour of account service information providers (AISP), payment initiation service providers (PISP), and card-based payment instrument issuers (CBPII). In UK, PSD2 was transposed into legislation with The Payment Services Regulation of 2017, leading to the foundation in the same year of the Open Banking Implementation Entity (OBIE), an independent organisation of the 9 largest retail banks in Britain and Northern Ireland aiming to implement open banking. Similar legislations were implemented for example in South Korea and Australia, favouring the diffusion of open banking.[5]See the Institutions and Numbers sections below. Also the market itself and the entry of new fintechs can give incentives to customers to share their financial information to obtain better services, in domains beyond payments, like loans, private banking, and so on.

In general terms, the reasons for opening access to information to third parties are three. First, enhancing competition. New third-party firms can use the information about the client to offer targeted services at better terms than the incumbent. Second, to favour inclusion. Because of a decline in costs, otherwise unbanked, unfinanced individuals may have access to financial services (see Bianco and Vangelisti in this issue). Third, to foster innovation. Competition and the focus on big data and programming interfaces is expected to favor the development of new tools, apps and services.

More specifically, the preamble of PSD2 emphasized the importance of increasing competition and guaranteeing free entry and a level playing field among incumbents and new participants.[6]Paragraph (4) of the preamble recites: “(…) equivalent operating conditions should be guaranteed, to existing and new players on the market, enabling new means of payment to reach a broader … Continue reading However, and remarkably, the Directive focused almost exclusively on data about payment services. In fact, AISPs are guaranteed access only to data of payment accounts, i.e., accounts “held in the name of one or more payment service users which is used for the execution of payment transactions”. All the same, it became increasingly clear to the industry that granting access to customers’ payment information would have also eased the provision of other banking and financial services and the development of a range of innovative products. These developments were also judged positively by regulators. In this regard, it is illuminating that EBA, in reply to a question raised by the Bank of Ireland on the interpretation of the Directive, on 13 September 2019 stated that an AISP is not limited to providing the consolidated information on the different account positions to the payment service user, but with the user’s consent it can also make this information available to third parties.

This evolution towards an even broader OB is envisaged to have the potential to change financial intermediation radically. But for this to happen, two key factors must be present: first, consumers must be willing to share their data, and second, the technology must be in place to ensure seamless data access through the use of APIs and cloud computing. If these conditions are met, OB is expected to change the way financial intermediation occurs.

Yet, there are considerable limits to the diffusion of financial information and to the use of such information for the purposes of enhancing competition, inclusion and innovation. Open banking is essentially about enabling transfers of data and information to some third parties, but not making it generally available. Key to the understanding of the potential impact of this innovation with respect to the three objectives above is therefore the assessment of how information will in fact be spread and used. If we take this perspective, we believe that the scope and the aims of open banking, although potentially groundbreaking, may sometimes be overstated, and its desirable implications cannot be taken for granted.

Information, in principle, is a public good: non rival and spreadable at no (marginal) cost. It gains private value precisely when different forms of protection privacy rules), or property rights (patents and copyright) prevent it from being used as a public good. Even in the case of open banking, information has value, be it for the incumbent or for other third parties, only if it can keep being privatized, at least partly. This creates inherent limits to its complete diffusion and disclosure.

These limitations are relevant for both the supply and the demand of information. On the supply side, OB does not open information concerning a given client to everybody. The owner of the information, the client, decides whether to make it available to well-identified counterparts. Whatever the source of open banking, rules or markets, the starting point is that the client remains the sole owner of the data and information on her or his transactions. This causes an issue of selection. How many potential counterparts are clients willing to disclose their private transactions to? Possibly a small number, because of privacy and because of reluctance to disclose sensitive information. Hence the supply of information will likely be limited.

As for demand, entry of third parties in a given segment of the financial markets will be enhanced by OB only if entrants have some way of preserving at least part of the value of the information. If it were not at least partly privatized by the new third party, the information would have limited value and there would be no demand for it and, ultimately, no entry in the market. Of course, even in a world where information is fully disclosed, capable providers can leverage on freely accessible information to offer highly differentiated products, not fully in competition one with the other, and create value for themselves anyway. Yet, inevitably the value of information declines with its diffusion. Again, this sets, from the demand side, a limit to how extensively information would be spread out.

An additional issue is how the information can be effectively used, and we will discuss this extensively in the third part of this editorial. One option, as argued above, is that the information is granted by the customer to a limited number of selected counterparts. Even opening up the information to a single new provider can be beneficial to the client: compared to the incumbent, the entrant may offer new services or the same services at better conditions. Of course, as argued by several contributions in this issue, things are different if the new entrant is an established bank or a Bigtech i.e., the big digital platforms with strong and entrenched market power in (non-financial) digital markets, rather than a fintech. Still, the ability to offer new services would anyway have a positive impact on competition and innovation, and possibly, through a reduction in the cost of services, to inclusion.

A different scenario could emerge if the data were transferred to a platform, which brokers numbers of potential suppliers of financial services. The platform matches clients with services, and the information likely stays with the platform, i.e., it is not necessarily transferred to the providers of the financial services. This because the platform is the intermediary in a two-sided market and has the technology to use the information for efficient matching. The client can therefore be better off. However, as we will argue below, the platform would enjoy monopoly power and information rents.

Network externalities would also be another distinctive element of this scenario. Only platforms with a very large client base and a large number of potential suppliers can effectively use clients’ data to offer efficiently targeted services. In other words, services based on the use of data and clients’ information generate network externalities which create new monopolistic power and limit the diffusion of information, even if it is used to broker the services of many potential suppliers. The market power built on relationship-based financial intermediation with restricted data access, would be replaced by a new network-based market power with open data. We will discuss the implications of OB for competition extensively in the third part of the introduction. In the following one we first examine which type of financial services can be affected by OB.

2. Open banking’s products

Which financial products will be mostly affected by open banking? A distinction is to be made between the existing financial products and the new ones that may be created.

Since open banking is mostly based on sharing payment information, an obvious starting point is to look at payment services. In this respect, payment initiation service providers (PISP) – newly allowed by PSD2 – may compete with existing intermediaries to become the originators of customers’ transactions, favouring a reduction in the costs and an increase in the speed and security of payment transactions. Customers, for example, may authorize a PISP to directly charge their bank current account after their purchases on internet, while simultaneously giving the seller the guarantee that the payment is successful. Since internet purchases are typically regulated through rather expensive credit-card transactions, the benefits of having PISPs is in this case evident

However, focusing on payment services only gives a narrow perspective on how open banking can enhance competition in the market for existing financial products. The possibility of accessing customers’ transaction data will likely impact all markets where this information has value for the provision of targeted services (Fama, 1985). An obvious example is the loan market. Convincing empirical evidence shows that there are significant complementarities between offering the same client a deposit account and a loan (Mester et al. 2002). In fact, it is a common practice for banks to require clients to open a checking account when they are granted a loan. Indeed, information on incoming and outgoing financial flows can be extremely valuable to assess ex-ante the level of a borrower’s riskiness and monitor ex-post its evolution. Financial intermediaries that can access these data have, therefore, a competitive advantage with respect to their competitors, leading to a bundling of the markets for deposits and loans. With open banking, each customer can allow an AISP (account information service provider) to access his transaction data and use them to choose what it considers the best potential lender. If authorized by the payment account holder, an AISP can also make the information available to any third party of his choice. A competing bank could therefore either act as an AISP or obtain information from an AISP on the customer’s transaction data. Clearly, this would whiten the competitive advantage that banks have when granting loans to their deposit holders. The product that would benefit from increased competition made possible by open banking would in this case be traditional bank loans.

Another practice that is rather common among banks is to offer investment products to their deposit holders when they see that their balances on the checking account exceeds levels consistent with normal operativity. In this case, the customer only receives an alert on his liquidity position, and she is free to invest in products other than those offered by the bank where she holds her checking account. However, the bank that has access to the customer’s transaction data still holds a first-mover advantage with respect to potential competitors, and it also has a comprehensive view of the time evolution of the liquidity position of the customer and of its average liquidity needs. Once again, with open banking, a customer can choose to make all this information available to any provider of saving products through an AISP, therefore reducing the competitive advantage of the bank where she holds the checking account.

A parallel issue, emphasized by Redondo and Vives in this issue, is the sharing of information on other financial positions of a customer regarding his saving and investment accounts or his loans and mortgages. While this is not yet a central part of the debate on open banking, there appears to be no reason why the logic applied to transaction data should not be expanded to information on other financial positions.

But open banking is not only expected to increase competition in the markets for existing financial services but also to foster the creation and supply of new financial services. This may open the door to an entirely new business model, where banks become platforms between customers willing to make their data available and sellers of financial services and financial intermediaries willing to offer them products that are specifically targeted to their individual characteristics. While the implications of this potential revolution on the banking industry will be discussed in more detail below, new products are being developed and it is to be expected that a wide range of additional ones will be made available in the future.

At the moment, the fastest growing services seems to be those helping to connect different accounts – e.g., bank, credit cards, and investment accounts – to provide a comprehensive view of the financial position of an individual or a firm. Providers such as Emma (https://emma-app.com/), Tink (https://tink.com/) and TrueLayer (https://truelayer.com) already offer these services, and are extending their line of business in new directions. For example, some providers already offer contemporaneous access to investment platforms, including those allowing to acquire crypto assets, while others offer secure authentication for the access to all different accounts. Other services already available include those that alert customers (and possibly their authorized connections, e.g., parents of minors) when a payment is required that exceeds a given amount or a regular pattern of purchases, helping detect scams and frauds.

As discussed by Bianco and Vangelisti in this issue, an interesting set of services are those targeted to less skilled individuals to manage their finances better, helping them to avoid recurring to credit card loans when cheaper bank loans are available as alternative or alerting them when outflows are exceeding the sustainable pattern that can be foreseen based on past evolution. Indeed, if directed by adequate policies, open banking can be a powerful tool to improve financial awareness and inclusion.

The next steps are difficult to foresee, but they will likely depend on the amount of information that can be extracted from payment data. Detailed information not only on the inflows and outflows of money from an account but also on their origin and destination might allow to reconstruct the pattern of purchase of an individual, making the step towards targeted product advertisement very short. Clearly, this once again opens the Pandora box of the role of Bigtechs such as Amazon or Alibaba, that already collect this information from a different angle. The role of policy and regulation will therefore be crucial in shaping future developments.

The possible uneasiness of many customers to share information with unknown new players gives a strong advantage to incumbents. And while this may be contrasted by enacting regulations that limit access to customers’ information only to reliable and possibly supervised entities, such regulations may not be easy to implement since open banking services are offered through the Internet and may therefore come from entities based all over the world, including countries with loose or non-existent financial regulations on open banking and data protection. Indeed, an adequate balance between limitations imposed by regulation and the need to allow market access to innovative entrants is yet to be found, but certainly necessary.

The market is in rapid evolution. Emma, for example, was founded in 2010 by two computer scientists and has still managed to survive being privately owned. Tink, founded in 2012 by two independent entrepreneurs, has been fully acquired by VISA in 2022, likely planning to leverage its huge customer base. Instead, Yolt, an open banking personal finance management application offered by the Dutch bank ING that started operating in 2017, has already closed its activities.

3. The impact on the industry

As discussed above, the actual implications of OB, though, depend on the availability of adequate data flows. If financial customers are not interested in sharing their data or have concerns about privacy, the entire chain of consequences may not materialize. The more mature digital markets provide useful lessons, showing how platform companies successfully convinced users to give up and share their data. Many digital markets offer “freebies”, or zero-price services, such as search engines and recommendations, with monetization taking place on other sides of the market, such as advertising to digital users. This business model has pushed users to embrace the idea, consciously or not, of providing personal information in exchange for services. This could serve as a model for financial markets too, but it will require the development of a platform-based business model that, as illustrated above, would allow retaining the information with the platform intermediary, a model still to come in financial markets.

Assuming that financial consumers are convinced to share data, the question is who are the other financial operators that will receive them. Rivera and Vives, in this issue, convincingly note that if data flow reaches other incumbent operators, like traditional banks, then even if potentially competing, we may not expect significant impacts of data, with additional risks. We know that data availability may induce a “winners-takes-all” condition when companies offer multiple products and services. Again digital markets are an example with their strategies that rely on the reusability of personal data for multiple purposes and services, with an envelopment effect on customers. A realistic outcome of this data flow is a possible increase of market concentration in the hands of fewer traditional financial intermediaries, uniquely placed to offer bundles of services. They are unlikely to be challenged by platforms also offering several products and services, as they are yet to be seen in markets.

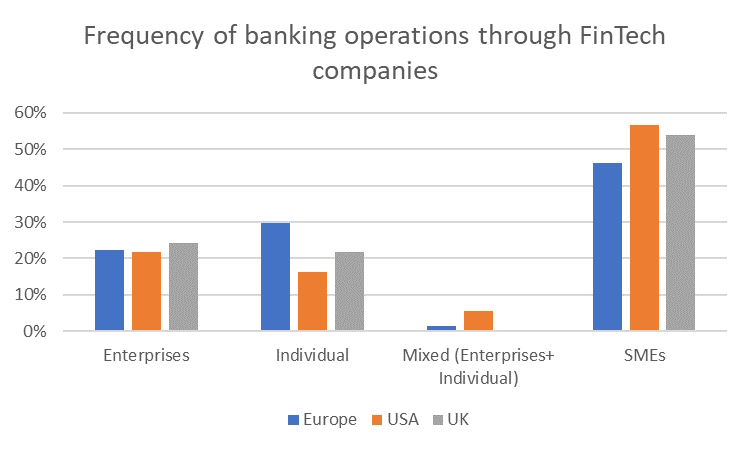

Clearly, as argued above, the flow of data mobilized by OB can also reach new players offering specialized and unbundled services, such as payment systems or lending services. Although in this case data could activate new tech players in financial markets such as Fintech, the implications on market structure and outcomes are, again, ambiguous and may not materialize quickly.

In fact, some recent papers in the academic literature (e.g. Parlour et al. (2022) on payments services and He et al. (2023) on lending) have highlighted that empowering Fintech players creates competitive pressure for traditional banks but, at the same time, can produce countervailing effects in terms of price and product discrimination and reduction of consumers’ surplus. Information is a peculiar input in financial intermediation. If the technology used by the new players to manage and elaborate information is significantly better than that of traditional players, this would enable them to segment the market and acquire the surplus of consumers of financial services. In other words, the unique nature of information as an input for financial activities can quickly generate excessive informational advantages for new entrants in terms of new services and better surplus appropriation.

Another risk could emerge when the data flow on financial transactions reaches mostly BigTech firms. These companies may extend their business envelopment and begin offering financial services (some already are, such as in China). On the one hand, this would increase competition, thus benefitting consumers of financial services. On the other hand, the strong envelopment tendency of a platform-business model should not be underestimated. We know from digital markets that these firms leverage detailed users’ information to capture users in several markets, with reinforcing feedback effect induced by even more data from the many services and products they offer. These are the consequences of strong complementarities between services and products (or indirect network externalities), reusability of data for several purposes and products, and specific properties of Artificial Intelligence algorithms employed to process these data.[7]Calzolari et al. (2023) discuss “Scale and Scope” properties of Machine Learning tools that rely on the amount of data and the diversity of data-sources and also study the implications for the … Continue reading Digital platforms have also prospered thanks to a feedback-loop mechanism where more users provide more data, allowing for better algorithms, predictions, and services, thus attracting even more users. OB has thus the potential to favor BigTech companies disproportionally and reinforce their business model with the inclusion and mutual reinforcement of financial services in their ecosystems. Interestingly, BigTech may value the flow of data originated by OB more than traditional banks for the same mechanisms described above and may be quicker and more effective in convincing financial market customers to share data with them.

Will platform-based financial operators able to bundle a variety of services emerge? It is difficult to say at this stage. They may materialize from a transformation of traditional incumbent companies, such as banks, or from BigTech entering the financial market. However, whatever the origin of this development, this could become a radically new scenario with platforms operating as matchmakers between customers of financial services and financial service providers . As a first step, the relevant data might possible refer to payments and deposits, as discussed above, possibly merging this type of information from different banking relationships. So traditional banks and AISPs are currently better placed to become financial platforms at an initial stage. However, the envelopment effects of Bigtechs should not be underestimated. In addition, “Banking as a Service” may further evolve, again under the impulse of regulation, markets and technology, into broader future developments, as it could very much involve many other financial services not only those typically related to banking. The properties of such a market configuration with broad gatekeepers are not necessarily very competitive, as the digital markets have shown and as discussed above.

Padoan, in this issue, indicates what could be effective strategies for traditional banks. Rather than insisting on traditional approaches, the quicker way into the innovation flow for traditional banks seems to be collaborating with new players (or acquiring them). However, we think this will not suffice if the platform model prevails. The changes needed for banks to transform themselves into platform operators and benefit from the network externalities that, if large, they already enjoy, are anyway deep. Offering fintech services in parallel is just one step in creating an enveloping “ecosystem” for their own products or for those of partners.

These long-run effects of OB are challenging to predict at this stage, as they combine several elements, in particular innovative technologies with consequences on screening and matching, flows of data, and business models that are new to financial markets.

In this uncertain and evolving environment, regulation should play a key role. For example, currently, in Europe, the Payment Service Directive “PSD2” only refers to data flowing to payment service providers but not to providers of other financial services, such as saving accounts, credit cards, mortgages, pensions, or insurance. Because of the implications of data flow discussed above, this limited first step into OB could be considered a wise approach. However, this is leaving much of the potential of OB untapped, and, as Dalmasso elaborates in this issue, the limited span of the directive may in itself constrain the potential broader benefits of OB. Regulation should continue to lead the development that OB will have on financial markets, also because increased competition and shifts in profitability will affect financial operators’ charter values, thus inducing increased risk-taking appetite with perilous implications for financial stability.

Currently, the promise of innovative banking platforms remains unfulfilled, as new entrants primarily focus on creating effective application interfaces rather than offering truly ground-breaking financial services. As previously discussed, the impact of OB may remain limited. However, once OB reaches full potential, it will undoubtedly reshape the financial landscape. And it will be essential to guide this process to prevent market tipping and concentrations similar to those seen in digital markets. Historically, policymakers believed that ex-post interventions would suffice to address market power issues in digital markets. However, as we have learned from experience, this is not the case, and regulators have had to catch-up with new regulations like the Digital Market Act (DMA) and the Digital Service Act (DSA). In the case of financial markets, proactive regulation will be crucial to avoid a similar scenario of late intervention. To achieve this, it will be useful to learn from the lessons of digital markets while creating regulations tailored to the unique characteristics of the financial industry. The challenge will be to strike a balance between regulations like DMA and DSA, coexisting with those designed explicitly for financial markets.

References

Calzolari G., Cheysson, A., and R. Rovatti (2023) “Machine Data: Market and Analytics”. SSRN, CEPT and European University Institute working paper.

Fama, E. F. (1985). “What’s different about banks?”. Journal of monetary economics, 15(1), 29-39.

He, Z., Huang, J., and Zhou, J. (2023). “Open banking: credit market competition when borrowers own the data”. Journal of Financial Economics, 147, 449-474.

Mester, L. J., Nakamura, L. I., and Renault, M. (2007). “Transactions accounts and loan monitoring”. The Review of Financial Studies, 20(3), 529-556.

Parlour, C. A., Rajan, U., and Zhu, H. (2022). “When Fintech competes for payment flows”. The Review of Financial Studies, 35, 4985-5024.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | University of Milan. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | European University Institute. |

| ↑3 | Roma Tre University. |

| ↑4 | Directive (EU) 2015/2366, known as PSD2, see the Institutions section below. |

| ↑5 | See the Institutions and Numbers sections below. |

| ↑6 | Paragraph (4) of the preamble recites: “(…) equivalent operating conditions should be guaranteed, to existing and new players on the market, enabling new means of payment to reach a broader market (…). This should generate efficiencies in the payment system as a whole and lead to more choice and more transparency of payment services”. |

| ↑7 | Calzolari et al. (2023) discuss “Scale and Scope” properties of Machine Learning tools that rely on the amount of data and the diversity of data-sources and also study the implications for the structure of a market for data. |