The sovereign-bank nexus continues to endanger the stability of the euro area. We present a proposal how to mitigate spillovers of risks from sovereigns to banks. It encompasses risk-based large exposure limits and risk-adequate capital requirements, with the large exposure limits being most important – both conceptually and empirically. Based on a recent snapshot of banks’ sovereign exposures, our analysis shows that the introduction of large exposure limits would necessitate substantial portfolio shifts. In contrast, additional capital requirements would imply rather small additional capital buffers. Our proposal also suggests how to mitigate procyclicality, inherent to large exposure limits.

1. Motivation

The close interconnection between sovereigns and banks is said to be one of the main reasons for the severity of the euro area crisis. In the global financial crisis, large-scale bail-out packages for banks raised many countries’ debt levels substantially, bringing even countries like Ireland that had followed sound fiscal policies before the crisis to the brink of sovereign default (Acharya et al., 2014). Reversely, sovereign risk spilled over to banks holding high levels of sovereign debt, endangering these banks’ solvency. Such risks became particularly apparent in Greece, where the haircut on sovereign bonds induced large losses at domestic banks.[1]There is another channel through which sovereign risk can spill over to banks: Doubts about public debt sustainability may lower expectations about a country’s ability to bail out its banks (Barth … Continue reading

Breaking the sovereign-bank nexus has been one of the central aims of the European Banking Union (European Council, 2012). In particular, the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) can mitigate the effects of banking crises on home countries. However, these reforms cannot break the reverse channel running from sovereigns to banks. In fact, this channel has been reinforced in the years after the global financial crisis because the home bias in banks’ bond portfolios has soared in many European countries (Acharya and Steffen, 2015; ESRB, 2015). It has been argued that banks in countries like Italy or Spain were using cheap liquidity from the European Central Bank in order to invest it in their home countries’ sovereign debt (Acharya and Steffen, 2015). This served both the states and the banks: It stabilized sovereign bond markets and allowed banks to earn a margin without even having to take account of underlying risks due to the privileged treatment of sovereign exposures in banking regulation. However, this came at the cost of strengthening the link between banks and sovereigns, thereby countervailing the intention of the Banking Union.

In addition to mitigating the sovereign-bank nexus, a removal of regulatory privileges is a prerequisite for other reforms of the euro area architecture envisaged to make the currency union more stable. One is the introduction of a mechanism to facilitate the restructuring of sovereign debt, which is necessary in order to render the no bail-out clause enshrined in the European Treaties credible (see Andritzky et al., 2016a; Andritzky et al. 2016b; Feld et al., 2016). Given the high levels of domestic sovereign debt in banks’ balance sheets, a restructuring of sovereign debt is hardly possible at the moment as it would jeopardize the stability of the banking sector. Another open issue is the hotly debated introduction of a European Deposit Insurance Scheme (EDIS). A change in the regulatory treatment of banks’ sovereign exposures is a prerequisite for common deposit insurance. If the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures remains unchanged, an agreement on EDIS is very unlikely.

2. Status Quo

Under current banking regulation in Europe, exposures of banks to European sovereigns are privileged in several ways. Whereas exposures to private debtors must not exceed 25 % of a bank´s eligible capital, such a limit does not apply to sovereign borrowers. In addition, there are no capital requirements for sovereign exposures in domestic currency. Finally, sovereign exposures are considered safe and liquid (level 1 assets) under the new liquidity regulation, while non-sovereign, non-high-quality exposures are subject to haircuts and caps under the liquidity coverage ratio.

In order to assess the impact of a policy reform, calculations are made based on individual bank data provided by the European Banking Authority (EBA). We rely on data from the stress test conducted in 2014 (referring to the end of December 2013) and from the transparency exercise in 2015 (referring to the end of June 2015). A total of 123 banks participated in the 2014 stress test, and 105 in the 2015 transparency exercise. The calculations focus on countries from the euro-12 Group except for Greece, since Greek banks were not included in the 2015 transparency exercise. The sample comprises 95 banks in 2014 and 2015. As of 2013, the aggregated assets of these banks comprised 77.3 % of total euro-12 bank assets (on the basis of the ECB’s consolidated banking statistics in 2013). For Germany, France, Italy and Spain, the ratios were 67.4 %, 99.1 %, 86.6 % and 89.3 %, respectively. Further details on the calculation method can be found in the Appendix to Chapter 5 of the Annual Report of 2015/16 by the German Council of Economic Experts (GCEE, 2015, item 473 et seq.).

Figure 1 depicts banks’ sovereign exposures for 2013 and 2015. The overall picture varies greatly from country to country. The largest share of sovereign exposures (in percent of own funds) is found in Belgium where banks’ sovereign exposures amount to more than 300 percent of own funds, followed by Germany, Luxembourg, and Italy where sovereign exposures are still above 200 percent. Banks in France, Ireland, and Finland have relatively small exposures towards sovereigns. The dark blue parts of the bars show the exposures towards domestic sovereigns. In some countries these exposures are substantial, being above 100 percent of own funds (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain) or represent more than 60 percent of the overall exposure towards sovereigns (Germany, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain). Hence, there is a significant home bias, particularly in the southern European countries, Ireland and Germany. Moreover, the exposure to other euro area countries is also substantial, whereas the exposure to other EU countries or non-EU countries is rather small (an exception is Austria). Whereas sovereign exposures had changed rapidly in the years after the euro area crisis, changes between end-2013 and mid-2015 are relatively small in most countries. The evolution is not homogenous: Some countries reduced their exposures (e. g., Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands), whereas other increased them (such as Austria and Luxembourg). In most countries the share of domestic exposures in total sovereign exposures declined mildly, with stronger declines experienced in Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain (around 10 percentage points).

Figure 1:

The risks associated with sovereign exposures vary across countries because sovereign ratings differ sharply. Figure 2 depicts the shares of different rating classes for different countries. The overall riskiness of banks’ sovereign exposures depends greatly on the rating of the home country. This explains why the overall risk from German banks’ sovereign exposures are relatively small, with around 90 percent being rated between AAA and A- according to Standard & Poor’s, whereas for Italian banks the same ratio is only around 25 percent. Even smaller numbers are found for banks from Spain and Portugal. Hence, a home bias in sovereign exposures has very different implications for bank risk, depending on where the bank is located. Nevertheless, current banking regulation treats all these assets as free of risk.

Figure 2:

3. The Proposal: Risk-adjusted large exposure limits and risk-adequate capital requirements

A reform of the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures should serve three objectives: It should

-

reduce concentration risks on bank balance sheets in order to prevent the insolvency of a member state from bringing about the insolvency of a bank;

-

increase banks’ loss absorption capacity in order to be able to better cope with a sovereign default;

-

reduce price distortions in order to mitigate incentives for sovereigns to borrow excessively and for banks to lend preferentially to governments.

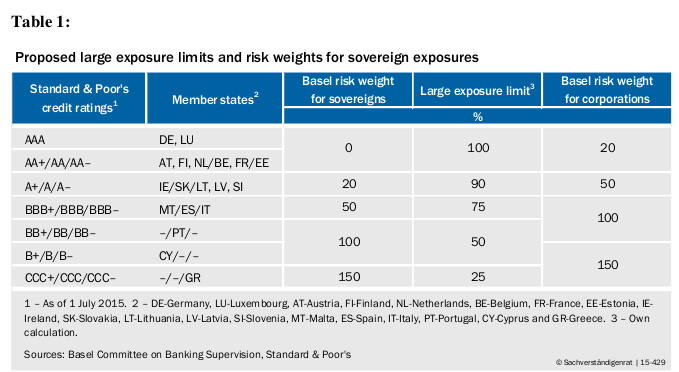

The German Council of Economic Experts (GCEE) has developed a proposal for removing privileges for sovereign exposures that rests on two key elements (GCEE, 2015): risk-adjusted large exposure limits and risk-adequate regulatory capital requirements. Large exposure limits are crucial to reduce the sovereign-bank nexus by limiting concentration risks directly and enforcing diversification. In addition, regulatory capital requirements increase banks’ loss absorption capacity and reduce price distortions. Capital requirements are to be based on the Basel sovereign risk weights. These are lower than the risk weights for corporate borrowers (see Table 1). Hence, sovereign exposures are still privileged relative to private ones. It should be noted that the Basel III leverage ratio, expected in 2019, already implies a regulatory capital requirement for sovereign exposures. For example, given a risk-weighted capital requirement of 8 %, a leverage ratio of 3 % would imply a fixed risk weight of 37.5 %.

Large exposure limits are to vary with the sovereign’s default risk because concentration risks in bank balance sheets primarily endanger financial stability in the event of a significant threat to a sovereign’s solvency. All sovereign exposures, even the safest ones, should be subject to a large exposure limit. For relatively safe sovereigns, the probability of default is very small but the impact of default for systemic stability would be huge. Moreover, given banks’ needs for holding a sufficient amount of liquid assets, risk-adjusted large exposure limits help to avoid that banks from countries with high credit ratings have to shift too strongly into riskier assets. The default risk could be determined by country ratings or alternative indicators that are less prone to subjectivity or manipulation, such as debt-to-GDP ratios. Different levels of government (i. e., state, federal, and municipal) should be viewed as a single unit if default risks are strongly correlated or a separate treatment would enable regulatory arbitrage.

For the countries with the lowest credit standing, the GCEE proposes the same large exposure limit as that for corporate exposures (25 % of eligible capital). The limit gradually increases to up to 100 % of eligible capital for countries with the best credit standing, using relative distances between risk categories as in the Basel sovereign exposure risk weights (Table 1).

4. Mitigating procyclicality

An important lesson from the recent crisis is that regulatory measures should not induce adjustment reactions that deepen a crisis. For instance, in the presence of large exposure limits, banks could be forced to divest sovereign exposures if their capital base contracts in a crisis. This procyclical effect could in turn increase governments’ financing cost and inhibit countercyclical fiscal policy. In addition, there could be abrupt credit rating adjustments in a crisis triggering sales of sovereign exposures to comply with exposure limits.

To dampen this effect large exposure limits should be based on long-term averages of sovereign ratings (or alternative measures, such as debt-to-GDP ratios) and of own funds, which would smooth any portfolio adjustments required under the regulation.

Risk-weighted capital requirements have, conceptually, the same procyclical effect for sovereign exposures as they have for private ones. This problem should therefore be solved within the existing macroprudential toolkit, i. e., via time-varying buffers.

5. Quantitative impact of the reform

To gauge the quantitative impact of the proposed reform, we are using banks’ balance sheet data from the EBA transparency exercise (see Figures 3 and 4). The current snapshot of euro-12 banks’ sovereign exposures suggests that the risk-adjusted large exposure limit as proposed by the GCEE is exceeded by about €562 billion of sovereign debt. Hence, substantial portfolio shifts would be needed to satisfy large exposure limits immediately. Excess exposures are distributed very unevenly across countries. In absolute terms, Germany, Italy and Spain are most affected. Interestingly, German excess exposures are driven mostly by publicly owned banks, whose excess exposures are substantial (in fact, larger than Italy’s total excess exposures). In relative terms (relative to total outstanding government debt), Spain, the Netherlands, and Germany are most affected, with maximum excess exposures being around 10 % of the respective country’s outstanding sovereign debt (see the red dots in Figure 3).

Figure 3:

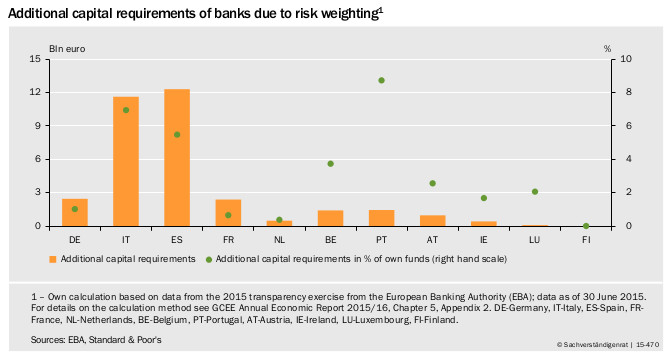

The effect of additional capital requirements is less dramatic. Given mid-2015 exposures, additional capital requirements for euro-12 banks in the EBA sample would amount to €33.6 billion, which corresponds to about 2.6 % of total own funds. This volume seems manageable compared to previous capital build-ups, such as in the run-up to the Comprehensive Assessment, which amounted to around €50 billion of common equity tier 1 (ECB, 2014). The largest capital needs are identified for Spain and Italy, amounting to around €12 billion each, which corresponds to 5.5 % and 7 % of own funds, respectively. In relative terms, Portugal is also affected rather strongly, amounting to 8.7 % of own funds. But overall the additional capital buffers are small implying that only a small additional loss absorption capacity would be generated. In the event of a sovereign debt crisis, such buffers would be no more than a drop in the ocean. This reinforces the point that exposure limits, rather than capital requirements alone, are key to severing the sovereign-bank nexus.

Figure 4:

6. Comparison to fixed large exposure limits

In order to assess the effects of our proposal compared to alternative models, we reran our calculations using four different specifications of large exposure rules (see Figure 5 for a summary of results). The first assumes a 25 % limit, as that for private exposures. The second prescribes a 50 % maximum exposure. The third model is our baseline. The fourth model is our baseline but additionally accounts for procyclicality by using average ratings over 5 years.

Figure 5 shows that our proposal leads to much milder exposure limits than the other models. Under a 25 % fixed large exposure limit, excess exposures would amount to €928 billion at euro-12 banks, which corresponds to up to 25 % of total government debt. Hence, our proposed model requires only roughly one half of portfolio shifts compared to a 25 % limit. A difference between models 3 and 4 arises only if sovereign credit ratings have changed within the considered time period. This is the case, for example, for Spain, which exhibits slightly smaller excess exposures under model 4 due to a rating downgrade in recent years.

Figure 5:

7. Transition to the new regime

A change in the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures requires a long transition phase. If the new rules were to be phased in over, say, ten years, it is likely that banks could achieve compliance by allowing their exposures to mature rather than disposing them actively. This would mitigate potential market disturbances. Regarding large exposure rules, an adjustment path could be specified for the phase-in period, starting, for example, from three times the final limits, which are then gradually reduced. Capital requirements could be introduced with a grandfathering clause so that only new exposures would be subject to the requirements. Then no deleveraging would be needed when the new rules are introduced. The cut-off date would have to be in the immediate past in order to avoid an incentive to stockpile still privileged sovereign exposures. With these provisions for the transition, it is also unlikely that the market would require banks to fulfill the additional requirements immediately.

In case of a fast implementation of the reforms, one could take advantage of the effects of quantitative easing (QE) on government bond yields. If QE were still in place, price effects for sovereign debt would be muted, which would facilitate the implementation of the reform. In the long run, however, prices will have to reflect different regulatory treatment.

8. Possible objections and alternative models

Our analysis shows that the reduction of concentration risk through large exposure limits is much more important than the introduction of capital requirements. Therefore, proposals relying on capital requirements alone should be discarded. Some opponents of large exposure limits have argued that their introduction would destabilize sovereign debt markets because banks can no longer play a stabilizing role in a crisis (Lanotte et al., 2016). While it may be true that banks have stabilized sovereign debt markets in some countries, it is doubtful that the benefit of such actions overcompensates the costs – namely the strengthening of the sovereign-bank nexus.

A more sophisticated version of capital requirements are soft large exposure limits to avoid cliff effects. For example, capital requirements could be zero below the given limit. If the limit is crossed, however, there would be increasing capital charges. The judgment of such proposals hinges crucially on their exact calibration. Our proposal with fixed exposure limits can be seen as the limit case of soft exposure limits with prohibitively high capital requirements once the limits are crossed. In their pure form, such soft exposure limits are likely to suffer from procyclicality: If bank capital falls, for example in a recession, the ratio of sovereign bonds over own funds would rise, implying higher capital requirements if the limit is crossed. This in turn would force the bank to deleverage.

Another issue is the question whether the regulation of sovereign exposures has to be dealt with at EU or even global level. While a more comprehensive approach would be clearly desirable, the situation in the euro area justifies a distinct approach. The major difference between euro area countries and Sweden or the US is that the former do not have the option of monetizing sovereign debt through their national printing press. Therefore, the euro area countries should not wait for a global agreement, which may never come about. An approach only in the euro area may seem as a disadvantage for euro area banks. However, the resulting stabilization of the euro area should overcompensate the costs of tighter regulation.

Our proposal is in principle compatible with proposals regarding the introduction of safe assets at the euro area level, the most important being the proposal of European Safe Bonds (ESBies) by Brunnermeier et al. (2011) and specified further by Brunnermeier et al. (2016) (see also Corsetti et al., 2015, 2016). These proposals attempt to create a safe European asset by bundling and tranching euro area sovereign bonds. In order to incentivize banks to hold such bonds, they could receive preferential treatment with regard to capital requirements and large exposure rules. Therefore, such proposals require a proper regulation of sovereign debt exposures in the first instance.

9. Conclusion

A removal of regulatory privileges for sovereign exposures is crucial to mitigate the link from sovereigns to banks. It is also an important prerequisite for the introduction of a mechanism facilitating the restructuring of sovereign debt and of a European deposit insurance scheme, which otherwise would be politically unfeasible. Our proposal encompasses risk-based large exposure limits and risk-adequate capital requirements, with the large exposure limits being most important – both conceptually and empirically. Any proposal has to deal with the problem of procyclicality in order to avoid destabilizing effects in crises. Moreover, the design of the transition process is crucial.

At the moment there seems to be a tendency to wait for decisions being taken in Basel, which may never happen due to the strong opposition from countries like the US or the UK. Therefore, the euro area should act on its own. It will be important to find political packages, including agreements on the regulation of sovereign exposures, common deposit insurance, sovereign debt restructuring, and the harmonization of insolvency law, that have sufficient benefits for all participating countries. Together these measures would have the potential to improve the stability of the euro area substantially. This gain should be priced in when weighing the pros and cons of such proposals.

References

Archarya, V., Drechsler, I., and Schnabl, P. (2014). A Pyrrhic Victory? Bank Bailouts and Sovereign Credit Risk. The Journal of Finance, 69 (6), 2689–2739.

Acharya, V., and Steffen, S. (2015). The “Greatest” Carry Trade Ever? Understanding Eurozone Bank Risks, Journal of Financial Economics, 115 (2), 215–236.

Andritzky, J., Christofzik, D., Feld, L. P., and Scheuering, U. (2016a). A Mechanism to Regulate Sovereign Debt Restructuring in the Euro Area, mimeo, German Council of Economic Experts, Wiesbaden.

Andritzky, J., Feld, L. P., Schmidt, C. M., Schnabel, I., and Wieland, V. (2016b). Creditor Participation Clauses: Making No Bail-Out Credible in the Euro Area, in: Filling the Gaps in Governance: The Case of Europe, edited by F. Allen, E. Carletti, J. Gray, and G. M. Gulati, European University Institute, Florence.

Andritzky, J., Gadatsch, N., Körner, T., Schäfer, A., and Schnabel, I. (2016c). A proposal for ending the privileges for sovereign exposures in banking regulation, VoxEU, 4 March 2016.

Barth, A., and Schnabel, I. (2013). Why banks are not too big to fail – Evidence from the CDS market. Economic Policy, 28(74), 335–369.

Brunnermeier, M.K., Garicano, L., Lane, P.R., Pagano, M., Reis, R., Santos, T., Thesmar, D., Van Nieuwerburgh, S., and Vayanos, D. (2011). European Safe Bonds (ESBies), Euro-nomics.com

Brunnermeier, M.K., Langfield, S., Pagano, M., Reis, R., Van Nieuwerburgh, S., and Vayanos, D. (2016). ESBies: Safety in the tranches. Economic Policy, forthcoming.

Corsetti, G., Feld, L. P., Lane, P. R., Reichlin, L., Rey, H., Vayanos, D., and Weder di Mauro, B. (2015). A New Start for the Eurozone: Dealing with Debt, Monitoring the Eurozone 1. London: CEPR.

Corsetti, G., Feld, L. P., Koijen, R. S. J., Reichlin, L., Reis, R., Rey, H., and Weder di Mauro, B. (2016). Reinforcing the Eurozone and Protecting an Open Society, Monitoring the Eurozone 2. London: CEPR.

ESRB (2015). ESRB report on the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures, European Systemic Risk Board, Frankfurt /Main.

European Council (2012). Euro area summit statement, Brussels, 29 June 2012.

Feld, L. P., Schmidt, C. M., Schnabel, I., and Wieland, V. (2016). Maastricht 2.0: Safeguarding the future of the Eurozone, in Rebooting Europe – How to fix Europe’s monetary union. VoxEu.org Book, edited by R. Baldwin and F. Giavazzi.

GCEE (2015). Focus on Future Viability, Annual Economic Report 2015/16, German Council of Economic Experts, Wiesbaden, Chapters 1 and 5.

Lanotte, M., Manzelli, G., Rinaldi, A., Taboga, M., and Tommasino, P. (2016). Easier said than done? Reforming the prudential treatment of banks’ sovereign exposures. Questioni di Economia e Finanza, Banca d’Italia.

Schäfer, A., Schnabel, I., and Weder di Mauro, B. (2016). Bail-in Expectations for European Banks: Actions Speak Louder Than Words. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11061, 2016.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | There is another channel through which sovereign risk can spill over to banks: Doubts about public debt sustainability may lower expectations about a country’s ability to bail out its banks (Barth and Schnabel, 2013; Schäfer et al., 2016). |

|---|