We propose a comprehensive, pan-European scheme to address the issue of non-performing exposures. We contend that securitisation is the most effective way to sell the bulk of troubled loans because it can rise the transfer price at a level closer to the real economic value, reducing the loss for the banks at bearable levels. Through a numerical example, we describe the main characteristics of a blueprint of securitisation to be implemented at a national level. We argue that this scheme could attract funds from a wide array of investors, while forms of public support can be worked out in terms compatible with the current European rules on state aid.

1. Why securitisation is the best way to get rid of European NPLs

The poor quality of banks’ loan portfolios seems to be at present the main unresolved issue in Europe. Non-performing loans (NPLs) in the Eurozone stand above €1 trillion; nothwitanding the discrepancies acroos banks and countries, more than one third of EU jurisdictions have NPLs ratios above 10% (EBA 2016). Such a bulk of NPLs is likely to have micro and macro-prudential effects. NPLs may impair the lending channel – therefore the transmission mechanism of monetary policy – due to the negative impact on banks’ profitability, capitalisation, and funding costs (ECB 2015). The low quality of loan portfolios can also revive the “diabolic loop” between banks and sovereigns, which forced the ECB to deploy ultra-accomodative monetary policies whose side effect is to depress banks’ net interest margin. Given the high interconnectedness within the Euro area financial system the risk of spillovers across banks and countries can also rise (ECB 2015; IMF 2016).

The issue has been so far left to national initiatives, as the European commission and Parliament, that avoided to adopt a comprehensive approach, pretending not to see the elephant in the room.

Since the inception of the financial crisis, many economists warned that a prompt and bold solution to improve the quality of banks’ assets was necessary (Spaventa 2008); others pointed to the example of the successful restructuring of the Nordic after the banking crisis of the early ‘90s (Borio et al. 2010). The response of the European and national authorities has not been up to these proposals and recently the IMF has warned on the urgency of a comprehensive solution (Aiyar et al. 2015). In particular the ECB stressed the need to solve the market inefficiencies that dampen the creation of a pan-European market for distressed loans (ECB 2016).

Our paper aims to contribute to the current debate by proposing a comprehensive, pan-European solution. We contend that securitisation is the most effective way for banks to sell their stock of troubled loans especially because it may reduce the wedge between demand and supply prices of NPLs, the major evidence of the inefficiencies of the market and the main cause of the delayed development of a secondary market for distressed loans.

A number of factors contribute to such a pricing gap (ECB 2016). The limited size of the market for distressed loans, the lack of detailed information on distressed portfolios, as well as the poor debt enforcement framework in several jurisdictions are all factors that raise the risk premium required by potential buyers and depressing the net present value of NPLs. In addition, the more the banks are convinced to have already followed prudential provisioning criteria, the less they are willing to sell doubtful loans at prices significantly below the book price. All these factors create a new version of the “lemon market” where participants are not willing to trade.

Against this backround, securitisation seems a preferable solution, vis -à- vis a straight sale of NPLs through, e.g., bad banks or asset management companies (Enria 2016), because it creates not only a market for distressed loans, but also a market for structured securities guaranteed by the pool of distressed loans. Because different degrees of protection are possible, several tranches of securities with different risk-return combinations can be issued. Thus, securitisation schemes may also reduce the need for public funds by attracting private investors with different risk/return profiles, including those with a relatively high level of risk appetite. As an effect of the tranching mechanism, the funding cost (the weighted average cost of capital) of the securitisation vehicle will be cut down, the more so if the scheme is backed by some form of public guarantee, within the limits of European rules. The next section will expand on this aspect and illustrate two examples of securitisation of NPLs.

2. A system wide securitisation scheme: two exercises

In this section, we first propose an example of a nation-wide securitisation structure for the Italian banking sector. We then extend the example to other European countries.

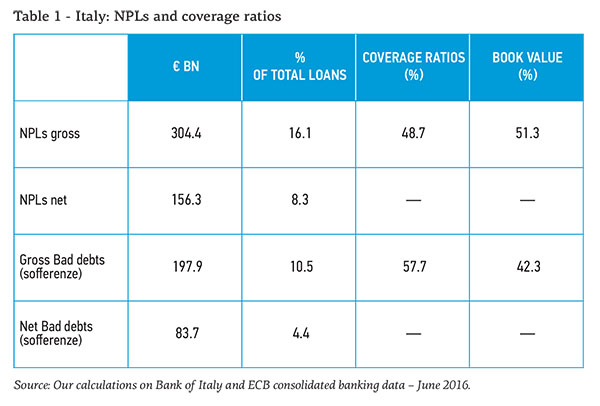

Italy. We use aggregate data on (gross and net) NPLs and coverage ratios in Italian banks (Table 1) and hypothize a securitisation transaction where the underlying portfolio is composed of the entire stock of Italian banks’ bad loans (sofferenze), i.e. the poorest quality component of the NPL aggregate that weighs more on banks’ balance sheet.[1]Without considering any further hair-cut from the recovery evalutation estimated by the banks, an expected recovery rate of 51.4 per cent has been calculated by adding back to the current book value … Continue reading

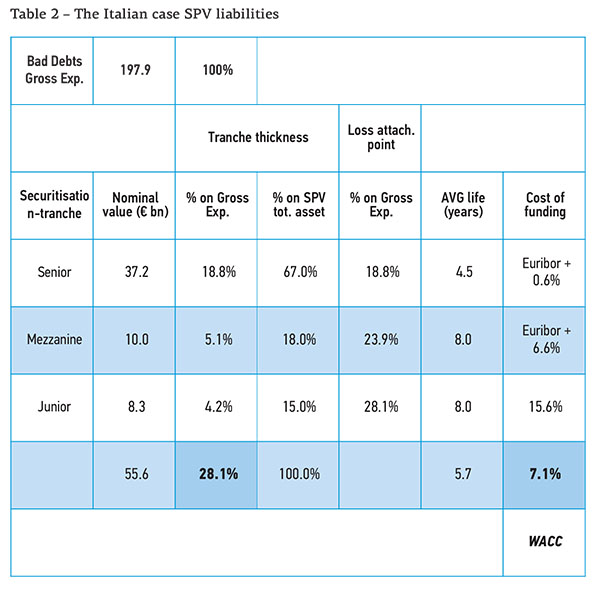

As in Lusignani and Tedeschi (2016), our nation-wide securitisation SPV scheme is based on the following assumptions:

- On the asset side, an average portfolio recovery rate of 51.4% and a 15% volatility of the overall gross exposure (equivalent to almost 30% of the expected recoveries);

- On the liability side, the weights of the different tranches are 67% for the senior notes, 18% for the mezzanine notes, and 15% for the junior notes;

- A state guarantee (as in the Italian “Garanzia cartolarizzazione sofferenze – GACS” scheme) is activated to cover the senior tranches that have received an investment grade rating (BBB- or higher) by an independent rating agency.

Table 2 summarises the main results of our simulation.[2]We estimate the par-yield returns for each tranche via Monte Carlo simulations using a risk-adjusted probability loss distribution of the securitized loans pool. We also use proper risk premiums … Continue reading The SPV’s weighted average cost of capital is around 7%. Adding legal and servicing fees (12% of recoveries) and taxes (tax rate 24%), the estimated bid price is about 28% of the bad debts gross book value. The yields offered to the three tranches could attract different types of investors. In particular, senior tranche yields are in line with the expected returns required by mutual funds while the mezzanine notes are compatible with the risk/return profile of institutional investors such as hedge funds and funds specialized in the NPLs. The junior tranches can be firstly addressed to private national entities such as the Italian Fondo Atlante. Some form of public support may be also introduced, as a compensation of the “first mover disadvantage”. Such a public support would be compatible with the “Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive” (BRRD), being the European banking system stability at stake (Enria 2016; Regling 2016).

The immediate loss for the Italian banks, net of the tax effect, will amount to nearly €21 billion (about 10% of bad loan gross exposure). Such a loss would represent the actual price paid by bank shareholders, as it will be directly deducted from the common equity tier 1.[3]The net loss is calculated as it follows. The net book value of bad debts in Italian banks, as of June 2016, is €83.7 billion (42.3 % of gross exposure). A sale price of € 55.6 billion (28.1% of … Continue reading At any rate, the heavy burden of almost € 200 bn (nominal value) of Italian NPLs can be concentrated in the placement of a junior tranche of 8 bn and a further loss for the banks of €21 bn.

By raising the sale price to 33% of gross bad debts the impact on the bank’s common equity will decrease: (1) the SPV total asset will rise to €65.3 billion (€197.9 billion x 0.33) and (2) the immediate net loss will be reduced from €20.5 to €13.3 billion. As for the liability side of the vehicle, because the higher the sale price the higher the risk borne by investors, the junior tranche’s size will increase accordingly (to €18 billion) in order to absorb such an extra (potential) loss, while the senior and the mezzanine tranches will remain the same.

Euro area. We re-run the same exercise on a larger sample of Euro area banks although we had to relax some assumptions due to the lack of granular data at European level (e.g., on the breakdown of NPLs and coverage ratios). We apply the same bad loan to total NPL ratio as in the Italian case (i.e., 65%), estimating a portfolio of € 975 billion (gross book value). [4]We estimate the NPLs transfer prices for Euro area countries by using World Bank data on average enforcing contract times and BCE data on average loans rates and coverage ratios. As before, we first set a sale price equal to 28% of gross exposure of bad assets in the area. In such a case, the disposal of bad loans would determine a gross loss for Euro area banks of about €70 billion (€51 billion net of tax). The value of the underlying portfolio (net of the loss) would be € 173 billion, financed by a senior note tranche of €116 billion (67% of total notes), a mezzanine note tranche of €31 billion (18%), and a junior note tranche of €26 billion (15%). As in the Italian case, the weighted average cost of capital would be nearly 7%. We then increase the sale price to 33% of gross exposure of bad loans in the Euro area: in such a case the total gross loss on disposal would be €46 billion (€34 billion net of tax). Hence, the asset size of the vehicle will be €197 billion, financed through the following tranches: €116 billion of senior notes, €31 billion of mezzanine tranches and by a larger junior tranche of €50 billion to absorb the extra potential losses associated to this second hypothesis.

In both examples for Italian and Euro area banks, we have not included (unlike Avgouleas and Goodhart 2016) a claw-back provision under which banks are liable for a certain amount of the future losses of the NPV. In our opinion, such a contingent liability would drag on banks’ balance sheet creating uncertainty in the market and reducing the banks’ incentive to securitize NPLs in bulk.

A coherent scheme for selling the bulk of NPLs could reduce the Italian banks’ NPL ratios from 16.1 to 5.6 % (gross value) and from 8.3 to 3.9 % (net value). The country with the largest amount of troubled assets would suffer an immediate loss of €13-20 billion and would need a junior tranche in the order of € 8-18 billion. At European level, the problem of NPLs could be downsized to a net loss for the banking system of about €34-51 billion and a junior tranche in the order of €26-50 billion. In other words, the securitisation solution can reduce the mountain of European NPLs by an order of magnitude.

3. Conclusion

The problem of NPLs has reached a dramatic dimension for many countries of the Eurozone and drags on the overall efficiency of the financial system and economic growth.

While there is a general consensus on the opportunity to remove NPEs from banks balance sheets, it is now clear that the market suffers from many failures that create a wedge between bid and ask price. Banks have therefore limited incentive to sell. We have shown that a securitisation scheme could drastically reduce the wedge and therefore the immediate losses for the banks.

Important to say, although key to resolve European banks’ problem loans, securitisation might not be sufficient. Together with a proper securitisation scheme, three further important features are, in fact, needed:

- The accurate due diligence of the underlying portfolio of non-performing loans by an independent external advisor.

- The sales of troubled assets must be accompanied by restructuring processes to reduce excess capacity and improve profitability. In particular: (i) The sale of the NPLs should be conditional to the approval by the prudential regulator of a medium-term plan aiming at restoring a sustainable long-term profitability; (ii) The sale of the NPLs should be an essential component of any resolution under the BRRD.

- More detailed and standardized information on the NPLs market are needed. As outlined by the EBA (2016), measures should be implemented to enhance transparency regarding the state of NPLs and associated factors, such as real estate collateral valuations. More and higher quality information will facilitate the sale process and lead to lower discounts in secondary market transactions.

More granular data are of course needed to draw more precise conclusions on the actual effects of a system-wide NPL securitisation. However, we believe that three circumstances make our proposal credible and effective. First, the estimated disposal losses in our examples are largerly in line with the capital buffers currently held by Euro area banks, as determined by the Supervisory review and evaluation (Srep) exercise. Second, the BRRD provides sufficient flexibility to allow for a public support for banks needing a precautionary recapitalization) where the financial stability is at stake. Third, the disposal of NPLs as a step of a broad restructuring plan approved by regulators, can assure the market (and politicians) that the entire scheme would work for restoring the long-term efficiency and profitability of the European banking system.

References

Aiyar, S., Bergthaler, W., Garrido, J.M., Ilyina, A., Jobst, A., Kang, K., Kovtun, D., Liu, Y., Monaghan, D., and Moretti, M. (2015). A Strategy for Resolving Europe’s Problem Loans, IMF Staff Discussion Note, September 2015.

Avgouleas, E., and Goodhart, C. (2016). An Anatomy of Bank Bail-ins – Why the Eurozone Needs a Fiscal Backstop for the Banking Sector. European Economy – Banks, Regulation and the Real Sector, 2016.2.

Borio, C., Vale, B., and von Peter, G. (2010). Resolving the Financial Crisis: Are We Heeding the Lessons from the Nordics? BIS Working Papers No 311 June 2010.

Bruno, B., Lusignani, G., and Onado, M. (2018). A securitisation scheme for resolving Europe’s problem loans, In Finance and Investment: The European Case edited by Mayer, C., Micossi, S., Onado, M., Pagano, M., and Polo, A. Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming.

Enria, A. (2016). Financial Markets 2.0 – R (evolution): Rebooting the European Banking Sector, speech delivered at the 7th FMA Supervisory Conference – Vienna, 5th October 2016.

European Banking Authority (EBA) (2016). Report on the Dynamics and Drivers of Non-Performing Exposures in the EU Banking Sector, 22 July 2016.

European Central Bank (ECB) (2015). Report on Financial Structures.

European Central Bank (ECB) (2016). Financial Stability Review (Special features), November 2016.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2016). Germany. Financial Sector Assessment Program, IMF Country Report No. 16/191, Washington DC, June 2016.

Lusignani, G., and Tedeschi, R. (2016). NPLs: a New Asset Class for Institutional Investors? Prometeia Working Paper, September 2016.

Regling, K. (2016). The Next Steps to Make Monetary Union More Robust, EMU Forum Oesterreichische Nationalbank Vienna, 24 November 2016.

Spaventa, L. (2008). Avoiding Disorderly Deleveraging, CEPR Policy Insight, n. 22, London, May 2008.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Without considering any further hair-cut from the recovery evalutation estimated by the banks, an expected recovery rate of 51.4 per cent has been calculated by adding back to the current book value of 42.3 per cent the time value effect at 4.25 per cent discount rate for a 5-year period. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | We estimate the par-yield returns for each tranche via Monte Carlo simulations using a risk-adjusted probability loss distribution of the securitized loans pool. We also use proper risk premiums calibrated on market conditions as of the evaluation date, to account for the volatility of recoveries risk and liquidity risk. |

| ↑3 | The net loss is calculated as it follows. The net book value of bad debts in Italian banks, as of June 2016, is €83.7 billion (42.3 % of gross exposure). A sale price of € 55.6 billion (28.1% of gross exposure) would imply a gross disposal loss of €28.1 billion for the originating banks. Once accounted for the tax effect (at a tax rate of 27.5 %), the net disposal loss for the banks would reduce to €20.5 billion (10.3 % of gross exposure). |

| ↑4 | We estimate the NPLs transfer prices for Euro area countries by using World Bank data on average enforcing contract times and BCE data on average loans rates and coverage ratios. |